Geopolitics: from hegemony to multipolarity

L’estira-i-arronsa geopolític dels últims anys entre Orient i Occident ha posat de manifest un canvi de paradigma que és cada dia més evident. Hem tornat a un món multipolar on l’hegemonia dels Estats Units va perdent força any rere any. Analitzem les causes i conseqüències d’aquest reequilibri i repartiment del poder global.

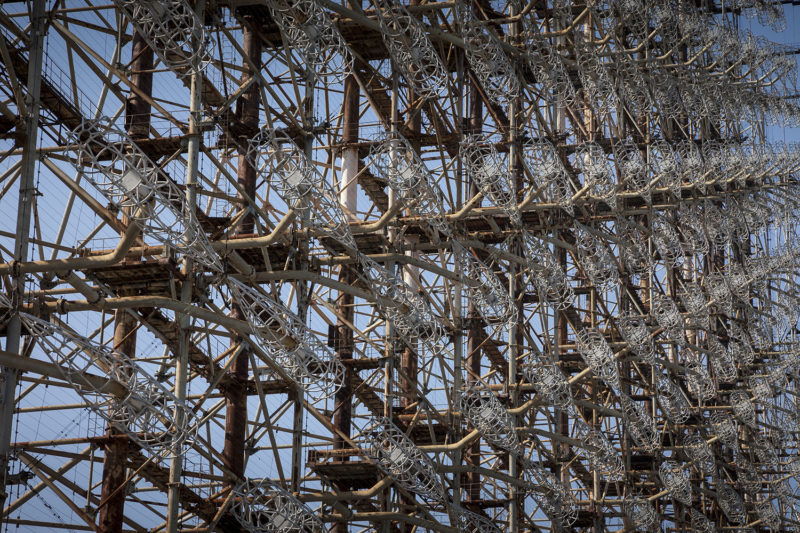

El món està més interconnectat que mai, però el poder està més repartit. La distribució del poder en la geopolítica mundial ha variat històricament entre els Estats. Del sistema bipolar establert durant el període de la Guerra Freda, en què dues grans potències compartien el poder, es va passar a un món unipolar després del col·lapse de l’URSS i el bloc comunista. Aquest canvi de l’ordre mundial va establir una hegemonia nord-americana substantivament basada en dues columnes: el poder militar i l’econòmic.

Tanmateix, l’abast i la preeminència de la influència geopolítica estatunidenca era única i anava molt més enllà de la definició d’una superpotència tradicional. D. Hubert Vedrine, ministre d’Afers Exteriors francès, va encunyar un nou terme, hiperpotència, per descriure un domini de poder que no només dictava l’àmbit econòmic, tecnològic o militar global, sinó que també incloïa l’imperialisme cultural que detallaven sarcàsticament els membres del grup de música alemany Rammstein en la coneguda cançó Amerika.

Dit això, la comunitat internacional no va trigar a plantar les llavors per desafiar aquest nou statu quo. Economies emergents, com el bloc format pels BRICS, van començar a situar-se de manera organitzada en l’escena internacional, donant sentit al concepte de món multipolar que definia les bases d’un nou ordre polític i econòmic.

L’ascens d’Àsia i el declivi d’Occident

El 1988, el líder xinès Deng Xiaoping va dir al llavors primer ministre indi Rajiv Gandhi

que l’arribada del ‘segle asiàtic’ estava lluny de ser un fet fins que la Xina, l’Índia i els països veïns es desenvolupessin. Tres dècades després, pocs dubten que estem vivint una nova època daurada del continent asiàtic. Àsia és la regió de major creixement del món i el contribuent més gran al PIB global, amb la Xina com la segona economia mundial.

Els cicles econòmics i els mercats financers se centren cada vegada menys en els Estats Units. L’ús i abús de les sancions econòmiques en vers qualsevol corporació o país, fins i tot països aliats, que no se sotmet als interessos del gegant americà, no fa més que consolidar els esforços per part de la Xina, Rússia i altres països no alineats al bloc geopolític occidental a crear sistemes econòmics alternatius.

Beijing, amb el seu enfocament en aconseguir la independència tecnològica i vinculació d’altres països a la Iniciativa del Cinturó i Ruta de la Seda (del seu nom en anglès Belt and Road Initiative), inverteix el seu capital, ajudant a aixecar les economies regionals de parts del món oblidades per Occident, o a les que els antics poders colonials exigeixen molt més, sovint amb l’ús de la força, per rebre molt poc a canvi. Tot un conjunt de múltiples aliances que divideixen i distribueixen encara més els centres de poder i influència.

Encara que ens trobem davant d’un reequilibri necessari i inevitable de l’ordre mundial, en última instància, que els Estats puguin fer un bon ús de la ressurgència d’aquesta nova tendència cap a la multipolaritat dependrà de la seva ubicació geoestratègica, demografia, recursos energètics i, sobretot, del seu poder econòmic, que demarcarà els límits de la seva autonomia relativa a les superpotències establertes.

11Onze és la comunitat fintech de Catalunya. Obre un compte descarregant la super app El Canut per Android i Apple. Uneix-te a la revolució!

They say that the 1978 Constitution is the pillar of Spanish democracy. Perhaps it is, but it is also its chastity belt. Everything that tries to breathe outside the centre is repressed in the name of unity. What was drafted to guarantee autonomy has ended up becoming a mechanism of submission: a text that confuses loyalty with obedience, and coexistence with silence.

When the current president of Castilla-La Mancha, Emiliano García-Page, declared that “all the money of the Catalans is ours”, he was not making an electoral jest, but expressing, without filters, the deepest truth of a system designed to turn solidarity into appropriation. From the Bourbon centralisation of the 18th century to the constitutional regime of 1978, Spain has built a model that confuses unity with submission and finds in Madrid its gravitational centre. What was historically an administrative necessity has today become a form of economic and symbolic domination.

While the capital proclaims itself the engine of progress, the reality is far more prosaic: Madrid does not generate wealth; it absorbs it. Its so-called “Madrid miracle” is the result of a fiscal and legal architecture designed to concentrate power and income, suffocating the productive territories that sustain the country.

The Direct Link with the “Emptied Spain”

According to the Spanish Tax Agency, Madrid contributed 19.5% of the national GDP in 2023, but declared 24% of the country’s highest incomes. The difference is not productivity but absorption: wealth is born in the periphery —Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Islands— and declared in the centre. The State has built a radial model in which everything —companies, institutions, media and sport— orbits around a single nucleus while the rest of the territory empties out.

With a 100% exemption on wealth and inheritance taxes and a tax policy tailored to large fortunes, Madrid has created an internal tax haven within the State itself. More than 25,000 high-net-worth individuals have established residence there in the last decade. Capital takes refuge, the periphery is exhausted, and the State looks on contentedly, because this imbalance serves its interests.

This concentration of wealth in the centre not only impoverishes productive territories but also accelerates the depopulation of large parts of the country. Rural and industrial areas, deprived of investment and economic activity, suffer a constant exodus of young people and an increasing dependence on subsidies. The so-called “Emptied Spain” is not a natural or demographic phenomenon, but the direct consequence of a State that drains resources, talent, and opportunities toward Madrid.

This unfair competition is not corrected — it is encouraged. The supposed constitutional solidarity is, in fact, a mechanism of legalised plunder across the entire territory. And when any region denounces this abuse, it is immediately branded as selfish. The paradox is striking: those who sustain the State are accused of wanting to break it.

The ‘Madrid miracle’ is nothing more than the result of a fiscal and legal architecture designed to concentrate power and income, suffocating the productive territories that keep the country alive.

Density as a Strategy of Domination

Demography was its first visible consequence. From 1950 onwards, the Meseta began to empty gradually, pushed by the need to feed Madrid with large doses of human capital.

That internal population flow was not spontaneous: it responded to a state strategy aimed at reinforcing the political and administrative centre. Madrid did not grow to be the economic engine of the country, but to become its seat of power.

That massive concentration transformed the city into an ecosystem of civil servants, administrators, public employees and middlemen, rather than a space for producers or innovators. It was not a geographical accident but the result of a political project of population density — because where population accumulates, representation accumulates; and where there is representation, there is legitimacy.

The parliamentary majority that sustains this status quo is not a coincidence. Forty-five percent of the seats in Congress are distributed between Madrid and the two Mesetas, a configuration that turns demographic concentration into permanent political hegemony. The Electoral Law, designed to over-represent the province as the voting unit, guarantees that the centre governs even without a social majority.

Thus, the two-party system —PSOE and PP— acts as the two faces of the same regime, alternating in power without ever altering its foundations. Madrid has fortified itself not only with laws and votes but also with the morality of power, under the conviction that everything central is rational and everything peripheral is suspect.

Over time, this induced demography and over-representation became the material and symbolic basis of central power. When democracy arrived, Madrid already concentrated enough electoral weight to condition any majority. Territorial balance ceased to be an objective and became a statistical anomaly. Since then, concentration has been interpreted as “efficiency,” and the emptying of the periphery as a natural consequence of the market.

But even here, the logic remains the same: dependence as a method of cohesion. The centre grows at the expense of the periphery, and the periphery remains loyal because it depends on transfers, contracts or institutional presence. As in every historical structure of domination, corruption functions as a mechanism of social peace — compensating grievances, buying loyalties and preventing reforms that could dismantle the system.

Thus, demographic policy, radial economics and structural corruption form a single mechanism. Power is not only exercised from the centre but fabricated by it — with population, resources and narratives all serving the same purpose: to preserve unity through dependence.

Corruption as the Binding Agent

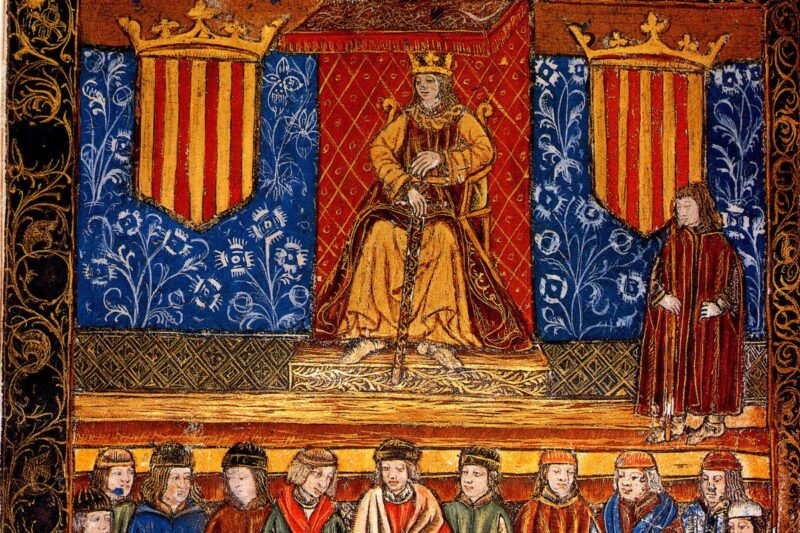

No structure can stand without cement — and in Spain, that cement is corruption. It is not a modern vice, but an organic inheritance. As early as the 11th-century León Courts, favour was the currency of power: bureaucracy existed to grant, not to administer. Under both the Habsburgs and the Bourbons, that courtly system was amplified and perfected until it became a method embedded in the State’s very core. When Spain was not yet Spain — merely a mosaic of kingdoms governed from the centre through the failed project of the Hispanic Monarchy — grace replaced law, and political loyalty was bought through economic obedience.

This pattern was never broken, only modernised. Where once there were royal favours, today there are public contracts; where there were viceroys, now there are government delegations; and where there were clienteles, now there are political parties. Corruption acts as the historical continuity of personalist power, the invisible glue binding the elites of the centre with the obedient peripheries.

And when obedience fails, the mechanism is debt. Creating debt is the modern way of subjugating territory. The autonomous communities, lacking fiscal sovereignty and forced to finance essential services with insufficient resources, are compelled to resort to the Autonomous Liquidity Fund (FLA) — an instrument created by the Ministry of Finance to provide liquidity… in exchange for structural dependence.

Through the FLA, what was once denied as financing —by imposing conditions and controls— is returned as conditional debt. Thus, need is transformed into political submission, and dependence into forced loyalty. Plunder and indebtedness are two sides of the same coin — one that always lands heads-up for the centre and tails for the periphery.

And when obedience fails, the mechanism is debt. Creating debt is the modern way to subjugate a territory.

Law as a Shield

The foundation of this architecture is not economic but legal. The 1978 Constitution, presented as a pact of coexistence, consecrated the unity of Spain as a dogmatic principle.

Article 2 defines it as “indissoluble”; Article 138 promises economic balance between territories, but without establishing effective mechanisms; and Article 156 recognises the financial autonomy of the regions… as long as it does not question unity. The result is a constitutional right to centralism, where every real decentralisation is perceived as a concession rather than a right.

The very legal structure reinforces this asymmetry. The State retains “basic” competences in almost every sphere —health, education, energy, taxation— under what the Constitutional Court calls “the basic equality of Spaniards.” This apparently neutral principle allows the central government to recentralise competences whenever it considers it necessary to “guarantee national cohesion” or “avoid territorial inequalities.” It is the legal mechanism that enables the State to decide on taxes, infrastructure or natural resources that, in other federal systems, would belong to the territories themselves.

The system of regional financing is a paradigmatic example: the regions collect only a limited portion of taxes but depend on annual transfers that the Ministry of Finance can adjust at its discretion. This generates a structural dependence that turns the principle of autonomy into an administrative fiction.

Within this legal and financial machinery, the banks play an essential role. Institutions such as La Caixa or Banco Sabadell —originally founded to channel Catalonia’s productive savings and credit— have ended up acting as structural pawns of the centralist system. Not out of ideology, but out of a need to survive within a regulatory, fiscal and political framework that rewards submission and punishes dissent.

The relocation of corporate headquarters after the 2017 referendum is the clearest proof: a legal operation presented as a “business decision,” but in reality the result of explicit political pressure from the State and the Bank of Spain, determined to use financial fear as an instrument of territorial control.

Thus, the very institutions that were created to support Catalonia’s productive economy have become guarantors of the status quo, ensuring that the flows of credit and investment continue to pass through the centre and that the structure of dependence remains intact.

In this way, Madrid can act as a fiscal paradise, applying bonuses and tax cuts that attract capital, while Catalonia or Valencia cannot fully manage their own resources without being accused of breaking Spain’s unity. The message is clear: the economic freedom of the centre is “efficiency”; that of others, “selfishness”.

Law thus becomes the shield of privilege, transforming inequality into a norm and dissent into a moral crime. In this way, centralism defends itself not with the army, but through legal codes, compliant banks and disciplined economic institutions that make power a matter of law, and law a tool of control.

When the Territory Questions the System

The Catalan independence movement was not —as it was portrayed— an identity delusion, but a political reaction to an unsustainable economic and institutional system. For decades, Catalonia had believed that self-government could coexist with constitutional loyalty, but the 2010 Constitutional Court ruling against the Statute of Autonomy shattered that illusion.

When the State declared unconstitutional several articles approved by referendum and ratified by Parliament, it made clear that autonomy had cardboard limits: self-government existed only as long as it did not question the centre. The demand for fair financing was not merely a budgetary issue; it was, in fact, a denunciation of the extractive model that feeds the heart of the State with resources from the entire eastern seaboard.

At the core of the economic debate appeared the fiscal balances, the investment deficit, and the radial infrastructures —all of which led to a political question of sovereignty, as they revealed that financial dependence is the true mechanism of submission.

In 2017, “el Procés” exposed that centralism is not a dysfunction of the system but its foundational essence. When part of the territory dared to question it, the State responded not with dialogue but with institutional reprisal and judicial mobilisation. In that response, the Bourbon monarchy played an especially active role, becoming the symbolic guarantor of the old order.

The application of Article 155, the intervention of the Catalan Government and the criminal prosecution of political and civil leaders revealed the stark reality: the Constitution is not a framework for coexistence, but a contract of submission that activates whenever someone tests its limits.

For this reason, the so-called “New Singular Financing” that the PSOE and its satellite parties now loudly offer to Catalonia is a complete contradiction in terms. Because if it were truly singular, it would break the fiscal uniformity that guarantees central power and would cause the constitutional edifice upon which the 1978 regime rests to implode.

The system cannot reform itself without destroying itself, because its strength lies in its rigidity. It was created to live off centralisation, and centralisation is incompatible with the economic freedom of the territories.

Madrid can act as a tax haven, applying bonuses and tax reductions that attract capital, while Catalonia or Valencia cannot fully manage their own resources without being accused of breaking Spain’s unity.

Behind the Mirage of ’78

As Montesquieu once warned, “when power is concentrated, freedom fades”. Spain has turned this maxim into a state doctrine. Madrid acts as an internal metropolis that governs through attraction and dependence — fiscal, media, political and sporting. Corruption fattens the machinery, law sanctifies its legitimacy, and demography guarantees its continuity.

That is why speaking today of “singular financing” is an oxymoron: no singularity is possible within a system designed to erase it. Madrid’s centralism is not a pathology — it is the very heart of the regime.

And as long as wealth continues to flow from the eastern seaboard to the centre, Spain will remain a state of dependencies with the appearance of a democracy. The true miracle is not Madrid: it is that the country still endures. Because —as always— power does not reside where work is done, but where the distribution of merit is decided. Perhaps the real question is not whether Spain can change, but whether it truly wants to.

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

Des de fa temps, la història ens retorna a un vell debat encara no resolt: què és ben bé Espanya? Una pregunta difícil que han hagut d’afrontar un grapat de generacions. Pel camí hi ha hagut tota meva de debats, promeses, triomfs i derrotes. I, malgrat tot, encara estem lluny de trobar una resposta.

Després de la llarga nit franquista, a Espanya se li van plantejar nous reptes a partir de 1975. L’Estat havia de trobar l’equilibri entre la reforma que proposava el govern franquista i la ruptura que demanava part de l’oposició. La solució pactada va ser la de transitar plegats cap a un nou règim fonamentat en una nova Carta Magna. La Constitució espanyola de 1978 es va dividir en deu títols i 169 articles. Al text, el terme “nació” apareix tan sols en dues ocasions, mentre que el terme “Estat” conté 90 entrades.

La primera i més important menció a la “nació” és la que obre el Preàmbul. “La nació espanyola, desitjant establir la justícia, la llibertat i la seguretat i promoure el bé de tots els que la integren, fent ús de la seva sobirania…”, comença el text fundacional, tal com si la mateixa nació redactés el que s’hi llegirà. Més endavant, aquesta “nació” autoproclamada expressa la voluntat de “constituir-se en un Estat social i democràtic de dret”, el qual desplegarà tots els seus òrgans i funcions.

La “nació”, objecte de litigi

Segons sembla, l’al·lusió a “els que la integren” es refereix als individus. En efecte, l’article 2 fonamenta la Constitució en “la indissoluble unitat de la nació espanyola, pàtria comuna i indivisible de tots els espanyols”, la qual “reconeix i garanteix el dret a l’autonomia de les nacionalitats i les regions que la integren i la solidaritat entre totes elles”. Justament aquest article és objecte de continu litigi.

Aquest famós article 2, en realitat, sembla que ens està dient que no són els individus els qui decideixen o desitgen una cosa, sinó que és la nació. Perquè la nació és qui ostenta la sobirania, no el poble. I qui anuncia aquesta proclamació de la sobirania tampoc és el poble, sinó que està personificada en la figura del Rei d’Espanya. Per tant, tot allò que integra la nació resulta confús.

“No són els individus els qui decideixen o desitgen una cosa, sinó que és la nació. Perquè la nació és qui ostenta la sobirania del poble, no el poble.”

El regne de les “nacionalitats”

Certament, l’al·lusió a les nacionalitats i a les regions apunta a la vella idea de la divisió territorial del regne. Aquesta paraula —“regne”— no s’esmenta enlloc a la Constitució. Cosa estranya, atès que Espanya es configura, en la seva forma, com a regne. Regne d’Espanya, en singular. Però aleshores, què són les nacionalitats? Què amaga el terme per referir-se a aquestes entitats orgàniques etnoculturals?

Sembla evident que es tracta d’un expedient púdic per al·ludir, sense anomenar-los, als antics regnes d’Hispània, a part de Castella, formats per: Catalunya, València, Mallorca, Aragó, Navarra, Galícia, el País Basc, Andalusia (i Portugal). Per tant, quin és el sentit i quina és la funció de les nacionalitats i de les regions? Impossible saber-ho, ja que aquests conceptes no tornen a aparèixer en tot el redactat de la Constitució.

Tot gira entorn de la “reconquesta”

Contra el discurs repetit com un mantra dins del sistema escolar franquista, l’aprenentatge d’Espanya es va articular en funció del concepte de “reconquesta”. Es tracta d’un terme historiogràfic —emprat encara en els currículums de secundària de Castella— que descriu el procés de recuperació del món feudal per sobre del món musulmà i jueu, perquè s’entén que els musulmans no eren els legítims propietaris de la geografia hispànica…

Aquest procés va arrencar poc després de l’arribada dels àrabs a la península Ibèrica al segle VIII i va finalitzar amb els Reis Catòlics al segle XV, els quals acabarien unificant “Espanya” com un Estat integral. Aquesta Reconquesta acabaria forjant “l’esperit espanyol”. O sigui, arguments històrics per justificar el nacionalcatolicisme imposat després de la Guerra Civil.

Tanmateix, no sembla que hagi existit mai ‘de facto’ una “nació espanyola”, és a dir, integradora de nacionalitats i regions, com ens vol fer creure la Constitució actual. Ni tan sols és segur que s’hagi consolidat mai com a Estat-nació, en el sentit modern. Ho veiem a continuació!

“No sembla que hagi existit mai ‘de facto’ una ‘nació espanyola’, és a dir, integradora de nacionalitats i regions, com ens vol fer creure la Constitució actual”

De la confederació a l’absolutisme

L’Estat dinàstic, iniciat pels Reis Catòlics, com hem dit, va acabar esdevenint un Estat absolutista. Abans de ser-ho, havia hagut de restringir el poder de la noblesa, forçar l’adscripció a la religió catòlica i cohesionar tot el poder en una devoció lleial al Rei. En contra del que pensen alguns, la llengua va restar al marge d’aquest esquema de poder. Per tant, no va ser mai un element unificador fins a principis del XVIII, encara que el franquisme intentés falsejar la història una vegada més.

El poder es va anar organitzant al voltant de cinc Consells d’Estat: Castella, Aragó, Itàlia, els Països Baixos, Portugal (1580-1640) i les Índies Occidentals. Per tant, els diferents territoris que configuraven la geografia de la Corona d’Hispaniae —plural d’Hispània— mantenien l’administració, la moneda i les lleis pròpies. En aquest sentit, es tractaria d’una mena confederació de nacionalitats, les quals conservaven les seves peculiaritats, furs i tradicions.

El predomini de Castella (que aglutinava Galícia, Astúries i Lleó) sobre els altres regnes existents de la península Ibèrica cada vegada va ser més evident, per extensió i població i, sobretot, després d’incorporar les Índies Occidentals al regne castellà, que ho va fer a títol de “descobriment”, amb tot el que va significar. D’aquesta manera, la progressiva translació de l’economia del mediterrani cap a l’atlàntic va comportar un canvi de paradigma en les relacions entre els diferents territoris que configuraven la Corona Hispànica.

Aquesta pluralitat, no sense sobresalts, va anar derivant cap a una major centralització del poder. Però el salt definitiu va ser després de la guerra de Successió i la subsegüent entronització de la dinastia borbònica al tron castellà. Entre 1707 i 1716, el nou rei Felip V va anar promulgant els coneguts Decrets de Nova Planta pels diferents territoris de la corona d’Aragó com a càstig per la seva rebel·lió i com a dret de conquesta. En canvi, aquesta pèrdua d’autonomia no va afectar mai ni Navarra ni les Províncies Basques, atès que aquests territoris havien estat fidels a la causa borbònica.

Va ser llavors quan Castella es va transformar en l’Espanya borbònica: una monarquia absoluta i fortament centralitzada. Prova d’aquest procés, Felip V escrivia el 1717: “He jutjat per convenient […] reduir tots els meus Regnes d’Espanya a la uniformitat d’unes mateixes lleis, usos, costums i tribunals, governant-se tots igualment per les lleis de Castella”. Així, com a resultat d’una repressió i per dret de conquesta, una Espanya castellanitzada per força es comença a configurar com un modern Estat (d’importació francesa) nacional (d’exportació castellana). Naturalment, la il·lusió va durar ben poc.

“De les nou constitucions espanyoles contemporànies, totes tenen en comú una mateixa afirmació: són una constitució de la monarquia i de confessió catòlica”

La il·lusió fallida de la “república federativa”

L’il·lustrat i escriptor José Marchena (1769-1821), exiliat a Baiona per escapar de la Inquisició, va escriure el 1792 un revelador informe per Jacques Pierre Brissot, un girondí i ministre d’assumptes exteriors de la República Francesa, sobre les dificultats d’implantar a Espanya una constitució semblant a la francesa del 1791. Les seves paraules són força reveladores: “França ha adoptat ara una constitució que fa d’aquesta vasta nació una república unida i indivisible. Però a Espanya, les diverses províncies de les quals tenen costums i usos molt diferents i a la qual s’hi ha d’unir Portugal, només hauria de poder-se formar una república federativa”.

En un sentit similar, el 1808, a Cadis, el cèlebre polític gironí, Antoni de Campmany va escriure, tot just començada la Guerra del Francès, en la famosa publicació ‘El Sentinella’: “… A França, doncs, no hi ha províncies ni nacions; no hi ha Provença ni provençals; ni Normandia ni normands. Tots s’esborraren del mapa dels seus territoris i fins i tot els seus noms […]. Tots es diuen francesos”. I més endavant detalla: “Llavors, què seria ja dels espanyols si no hi hagués hagut Aragonesos, Valencians, Murcians, Andalusos, Asturians, Gallecs, Extremenys, Catalans, Castellans? Cadascun d’aquests noms inflama l’orgull d’aquestes petites nacions, les quals configuren la gran nació”.

Dècada rere dècada, de les nou constitucions espanyoles redactades durant l’edat contemporània (1812-1978), totes tenen en comú —amb petits matisos—, una mateixa afirmació: són una constitució de la monarquia i de confessió catòlica, la religió del Rei i de la nació. Per tant, la unitat de la nació és la unitat de la monarquia.

Existeix, doncs, una nació de nacions?

11Onze és la fintech comunitària de Catalunya. Obre un compte descarregant l’app El Canut per Android o iOS. Uneix-te a la revolució!

El rescat del sistema bancari espanyol va requerir la injecció de més de cent mil milions d’euros, que no van servir per a revitalitzar l’economia. Era possible una altra fórmula? La veritat és que Islàndia va sortir enfortida de la gran crisi financera que va viure entre 2007 i 2009.

Ara fa deu anys de la decisió del Govern espanyol de prendre el control de Bankia, en aquell moment la quarta entitat financera més gran de l’Estat. Ho va fer convertint en accions un préstec de gairebé 4.500 milions d’euros. L’entitat va acabar fusionant-se al 2020 amb CaixaBank, o sent absorbida per aquesta última entitat, segons com es vulgui veure.

“Aquí no hi ha un cost per als contribuents espanyols”, deia Luis de Guindos, ministre d’Economia, durant els dies de la intervenció. Però el que en principi no anava a tenir cost per a l’Estat ha acabat amb una injecció de capital de més de 22.000 milions d’euros, tot i que potser s’acaba recuperant una part algun dia.

Bankia és una més de la llista d’entitats financeres rescatades per l’Estat espanyol arran de la crisi financera de 2008, que també va portar a la intervenció de Caja de Ahorros del Mediterráneo, Banco de Valencia, CatalunyaCaixa, NovaCaixaGalicia, Unnim, Caja de Ahorros de Castilla-La Mancha, Cajasur, Banco Mare Nostrum, Banc CEISS, Banco Gallego, Banca Cívica, Grupo Cajatres, Liberbank i Caja Rural Mota del Cuervo.

En total, el Tribunal de Comptes ha quantificat en més de 122.000 milions els recursos destinats a la reestructuració d’aquestes entitats, que han acabat absorbides pels grans bancs espanyols. El Fons de Reestructuració Ordenada Bancària (FROB) va comprometre més de 77.000 milions d’euros; el Fons de Garantia de Dipòsits, més de 35.000 milions, i el Banc d’Espanya, gairebé 10.000 milions.

Diners difícils de recuperar

El Banc Central Europeu reconeixia en un informe elaborat al 2015 que les injeccions de capital a la banca espanyola es van realitzar de manera que la devolució dels diners públics era inviable.

En realitat, es va tractar d’una espècie de regal de milers de milions al ‘lobby’ bancari. Molts títols es van adquirir per un valor superior al real i era evident que una part important dels actius traspassats a la Societat de Gestió d’Actius Procedents de la Reestructuració Bancària (Sareb) generarien pèrdues milionàries a l’Estat. Segons estimacions del Banc d’Espanya, la festa acabarà costant al contribuent un mínim de 60.600 milions d’euros.

És justificable aquest desemborsament públic? Després de l’experiència de la Gran Depressió estatunidenca pel crac de 1929, en la qual la caiguda del sector financer va tenir un efecte demolidor en la resta de l’economia, molts experts han defensat la conveniència de rescatar als grans bancs per a evitar el col·lapse econòmic.

L’argument és que per als contribuents resulta menys onerós el rescat que les conseqüències de la recessió. Tot i això, no tots els països han seguit l’ortodòxia acadèmica.

La via islandesa

L’any 2000 Islàndia era un país de 300.000 habitants amb un PIB que no arribava als 10.000 milions d’euros. Però en pocs anys el seu sector bancari es va hipertrofiar gràcies a suculents interessos que van atreure gran quantitat de dipòsits des d’altres països.

El boom de les seves entitats financeres va fer enlairar l’economia del país, que més que va doblegar el seu PIB entre 2001 i 2007. El crèdit fluïa a l’illa com si d’un mannà es tractés i la corona islandesa es va disparar en el mercat de divises.

No obstant això, la fallida de Lehman Brothers al setembre de 2008 va punxar la bombolla islandesa. En pocs dies, les tres principals entitats financeres de l’illa (Glitnir, Landsbanki i Kaupthing) van declarar suspensió de pagaments.

En lloc d’injectar milers de milions en aquests bancs privats, Islàndia els va deixar caure i va crear noves entitats per a gestionar les restes del naufragi. Després de múltiples protestes, la dimissió d’un Govern i diversos referèndums, el país va decidir salvaguardar els dipòsits dels islandesos i va rebutjar fer-se càrrec de l’enorme quantitat de dipòsits estrangers.

És cert que aquesta via no va sortir gratis als contribuents, ja que Islàndia va destinar un 20% del PIB a fer neteja del sector, segons estimacions de l’OCDE. Però l’economia es va recuperar amb energia en els anys següents. Després d’una caiguda de gairebé un 40 % entre 2007 i 2009, el PIB va tornar a remuntar i al 2017 ja superava els nivells previs a la crisi. Per contra, Espanya mai ha tornat a igualar els nivells de 2008.

11Onze és la comunitat fintech de Catalunya. Obre un compte descarregant l’app El Canut per Android o iOS. Uneix-te a la revolució!

When Europe emerged from the chaos of the Thirty Years’ War in the mid-17th century, it decided to reorganize itself. With the Peace of Westphalia (1648) and, shortly afterward, the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), the continent consecrated a new political architecture: each king would rule within his own territory, and that territory would be enclosed by a legal border. From that territorial redesign, a new world was born —that of the nation-states— a legal invention that would turn geography into property and diversity into suspicion.

For centuries, this system functioned with brutal yet solid efficiency, giving rise to regular armies, stable currencies and bureaucracies capable of controlling the territory with the same coldness with which they drew maps. The border ceased to be a zone of exchange and became a line of separation. And with it, Europe believed itself immortal.

But time erodes all geometries. In the 21st century, the lines drawn at Westphalia have begun to melt, as if the borders of Europe’s political map were made of wax. This has allowed capital to circulate without an address, companies to operate without a homeland, and people to move more out of necessity than vocation. In this new landscape, the old nation-state looks increasingly like an empty fortress: perfect in form but hollow in substance. In fact, it feels as if we are once again inside Thomas Mann’s “The Magic Mountain” (1924), in which the author brilliantly portrayed the 1920s as a Europe enclosed, sick and fascinated by its own fever.

The inner fracture

Today’s Europe suffers a crisis that is not moral, but demographic and territorial. Its societies are ageing at a dizzying pace, which causes their interior spaces to fade progressively and the welfare system —built on the premise of an abundant active population— can only be sustained thanks to the massive entry of human capital.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of workers from diverse backgrounds arrive —who, like the barbarians of the 4th century, do not come to destroy but to sustain the system— preventing collapse. This new human capital provides the necessary workforce, contributes net tax revenue and ensures that social contributions continue to feed public services. Without them, the wheel of welfare would stop instantly, accelerating Europe’s decline.

But Europe has not yet understood that, like 5th-century Rome, it will only survive if it is capable of transforming its political structure to organically integrate all this human capital.

This population crisis overlaps with another of a geographical nature. The continent’s night map shows a brightly lit coastline and a vast dark interior. The great metropolises —London, Paris, Barcelona, Milan, Madrid, Berlin— concentrate wealth and power, while vast rural areas are emptied to the point of becoming human deserts. This is the new invisible frontier now taking shape, where divisions are no longer between states but between useful territories and abandoned ones.

Nation-states, born to defend their unity, now find themselves divided from within. The fiscal balance, redistribution and territorial cohesion that sustained the social pact have cracked. The south pays for the north’s demography; the west lives off the labour of the east; the centre concentrates what the peripheries produce. The result is an imbalanced system reminiscent of the Late Roman Empire: bureaucratic, indebted and dependent on human flows it can no longer control or understand.

In fact, this is the model of state that 18th-century colonialism —French, English, or Dutch— exported across the world. The same that, with supremacist arrogance, drew lines over empty maps and imposed by force of arms the principle of territorial sovereignty as a universal formula, stripped of any local grounding. In this way, European powers projected onto Africa, Asia, and the Americas their dream of rational order through the creation of straight borders, traced with a set square across deserts, jungles or unknown mountains, even if this meant separating peoples who shared language, culture and economy, or merging them with historical enemies under the same flag.

The result was an artificial geography built upon a state architecture with no social foundation. And when those colonies achieved independence, they did so under a poisoned inheritance: the nation-state had been an imposed model without a society to sustain it. The civil wars, genocides and absurd borders of the 20th century are the bill.

Because Europe, in trying to civilize the world, ended up universalizing its own mistakes. And perhaps now, faced with its own internal crisis, the Old Continent is beginning to understand that that model of rigid border and single identity was not a historical truth but an anomaly of its past.

Europe has not yet understood that, like 5th-century Rome, it will only survive if it is capable of transforming its political structure to organically integrate all this human capital.

The future lies in the limes

During the Late Empire, when Rome began to collapse under its own weight, the Germanic peoples crossed the limes not to destroy the Empire but to become part of it. They wanted to be Romans and, contrary to popular belief, their contribution —labour, soldiers, farmers, and taxes— was essential to keep the system alive. From that moment on, this new human capital allowed lands to continue being cultivated and kept the State functioning.

Today, history seems to be retracing the same steps. The Europe that invented the concept of the nation-state sees its model running out while new populations sustain its continuity. In essence, it is the same process the Old Continent experienced in the past, when it needed those “barbarians” to keep being what it was.

Perhaps this will lead us into a new Late Antiquity, a kind of transitional moment in which sovereignty will no longer be measured by control of territory but by the ability to manage the flows that cross it —capital, people, data, or ideas. And any State that fails to understand this and entrenches itself will likely be condemned to dissolve.

The Mediterranean once again —which was once the economic heart of the world— holds the key to the future. It is the place where the two halves of the old system meet: the ageing north and the growing south. If Europe wants to be reborn, it must look again towards its Mare Nostrum and understand that its survival depends on the permeability of what modernity sought to make impermeable.

When a civilization enters decline, history offers two options: raise walls or build bridges. Rome survived as long as it knew how to integrate, and disappeared precisely when it began to exclude. Even so, Europe is still in time to straighten its course. Perhaps the end of the nation-state will not be a collapse but a return: one in which geography acts as truth and history as a warning.

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

Throughout history, the concept of a border has been subject to multiple interpretations. For the Romans, borders were conceived as a zone of influence and control rather than fixed lines. In contrast, in medieval times, a border was a dynamic, flexible space, often laden with commercial and political opportunities. However, from the mid-17th century onward, the Pyrenean border became a legal line of separation between territories, acquiring a distinctly administrative character.

This new border conception had profound consequences for the political configuration of Europe. The reorganization of the political map favoured the consolidation of new state sovereignties but also led to the rupture of cultural, social, political, and economic realities that had been cohesive for centuries. Thus, any person, community, or territory that challenged this new principle of sovereignty—in the absolute and indivisible unity of the State—faced harsh military and political reprisals.

Following this evolution, the concept of a border has been widely analysed by various disciplines in the social sciences. Until recently, these studies were influenced by political-historical perspectives that interpreted the border as a fundamental element for defining states. Examples of this can be found in 19th- and 20th-century political theories, which justified the precise delineation of territory and the strategic use of borders as instruments of defence and state sovereignty. Over time, politics allowed the state to associate its identity with the concept of a nation, thus forcing the unification of diverse historical realities under the nation-state model, a process that ultimately generated internal tensions.

However, more recent studies in historical geography have redefined the notion of a border. It has been demonstrated that borders are not simple, immovable physical lines but dynamic contact spaces where constant social, economic, and cultural interactions occur. This perspective dismantles the traditional idea of a border as an impenetrable wall and redefines it as a transition and relationship zone. A paradigmatic example of this new perspective is the doctoral thesis of Oscar Jané Checa, which provides a rigorous and well-documented analysis of the construction of the Pyrenean border in the 17th century and its impact on Catalonia. Studies like this help to understand that the border is not just an imposed division, but also a living space that shapes and transforms the societies that inhabit it.

Geographical elements that shape an identity

The origins of the Països Catalans date back to the Carolingian era when, under the policy of ‘Renovatio Imperii’, the territories south of the Pyrenees—from Pamplona to Barcelona—were organized into defensive territories against the Andalusian world. Until the 13th century, the Counts of Barcelona maintained interests north of the Pyrenees, but after the Battle of Muret, expansion was redirected toward the southern peninsula and the eastern islands, shaping what we know today as Països Catalans. This process was made possible by three fundamental geopolitical elements.

The first key factor was the sea, understood as the main axis of communication and territorial cohesion. This allowed the establishment of a wealth triangle between Valencia, Mallorca, and Barcelona—a model that, despite centralist pressures, persists today as an economic and cultural reference.

The second determining factor was the difference in altitude between the Castilian plateau and the Mediterranean coastline. The physical structure of Països Catalans has favoured, since ancient times, a high population density in coastal areas and low valleys, in contrast to the higher and more isolated inland regions. This geographical reality has led to different population models: a coast open to communications and exchange, while the interior has maintained a more dispersed and self-sufficient population.

This distribution can be observed in a night map of the Iberian Peninsula, where the most illuminated areas correspond to the Ebro Valley -Zaragoza-, the Mediterranean coast -from the Roussillon plain to Murcia-, the Guadalquivir Valley, the mouth of the Tagus River, the small valleys of the Cantabrian coast and the centre of the peninsula, as it is the capital. The rest of the territory remains in the dark, indicating a low demographic density that reflects the reality of empty Spain.

The third key factor is the presence of a vast demographic desert known as the Celtiberian Mountain Range. This area, with an extremely low population density, has historically remained disconnected from other peninsular regions. It is the second least populated area in Europe, after Finnish Lapland. This desert extends from Tortosa to the north with Zaragoza, to the west with Madrid and to the south with Ciudad Real. This population vacuum has acted over the centuries as a natural barrier that has preserved the Països Catalans from direct contact with the peninsular interior, reinforcing its geopolitical uniqueness.

This physical separation has also been reproduced in the north, where the French noon has similar characteristics, although to a lesser extent. This explains why the Catalan territories of the French State (Roussillon) and the Spanish State have historically lived isolated from each other. Only some accesses, such as the Ebro Valley -following the waterway through the Tortosa-Lleida-Zaragoza axis and the Huerta of Alicante, have allowed a certain connection with the interior.

This geopolitical framework, together with the language as a distinctive element, has consolidated the idea of a country with a homogeneous structure and its meaning. Beyond the linguistic unity from Salses to Guardamar, the geographical configuration explains the territorial continuity of the Catalan language, which expanded following a logical path without significant natural obstacles.

“The sea is understood as the main axis of communication and territorial structuring. This made it possible to establish a triangle of wealth between Valencia, Mallorca and Barcelona, a model that – in the face of centralist attacks – persists today as an economic and cultural reference.”

Dynastic rivalries and family clashes

After the Castilian Civil War (1475-1479), the two largest territories of the Iberian Peninsula—the Kingdom of Castile and the Catalan-Aragonese Confederation—formed a new political entity known as the Hispanic Monarchy. This dynastic state was structured around two key elements: the army and foreign policy. However, other fundamental aspects of the modern state, such as borders, currency, laws, and institutions, remained completely separate. Initially, the Catalan-Aragonese Confederation maintained its institutions and legal systems, leading to recurring tensions with the Hispanic monarchy in the following centuries.

The discovery of rich metal deposits in Mexico and Peru led to the founding or refounding of American cities that played a strategic territorial role in ensuring a constant flow of wealth to Castile. This transformed Castile into an economically powerful actor but also into a state that spent exorbitant sums to construct its idea of civilization, based on Catholicism. This obsession often led to numerous conflicts of various kinds, such as theological disputes, dynastic struggles, commercial issues, and monumental architectural projects. In addition, at the beginning of the 16th century, the main Communities of Castile were forced to assume a considerable tax to finance the purchase of the imperial title by the Habsburg family, which triggered the famous Revolt of the Commoners.

With the acquisition of the imperial title, France – ruled at that time by the Valois dynasty – perceived the Habsburgs as its main enemy, since with that purchase, the Habsburg family came to control most of the territories surrounding the French kingdom. This situation further aggravated France’s economic challenges in the mid-16th century, as the Habsburgs indirectly conditioned commercial mobility and restricted opportunities for growth.

As a result, key sectors such as agriculture – especially vines, wheat and other cereals – and textile manufacturing, which were the economic engine of the French kingdom, were limited by the difficulties of access to the markets of Italy and the United Provinces. Key cities such as Lyon, Paris and Marseilles experienced the effects of this blockade, and their commercial freedom and capacity for economic expansion were curtailed.

For this reason – despite being an eminently Catholic society – France supported the Dutch and German Protestant factions, to counteract Hispanic expansionism. This strategy was part of the geopolitical principle of the “Grand Dessein”, which sought to surround the Hispanic dominions with hostile allies to wear down the influence of the Habsburgs in Europe. As a consequence, during the following centuries, the Hispanic Monarchy and France would clash fiercely for control of Europe.

Change in European economic dynamics

At the beginning of the 17th century, the American mines began to show signs of depletion, a trend that would become more pronounced as the century progressed. This slowdown in the inflow of precious metals endangered the economy of the Hispanic Monarchy, which -to maintain its high rate of spending – was forced to borrow from German and Genoese banks. This financial dependence led to a generalized increase in taxes and a strong fiscal pressure on the entire Hispanic society. Thus, the monarchy was forced to look for new financing mechanisms, which would lead it to demand greater contributions from the different kingdoms of the Hispanic Monarchy.

In this context, in March 1626, Barcelona received King Philip IV, who had arrived in the city to swear the Catalan constitutions. However, the real purpose of the visit was to unblock the ambitious plan of the king’s minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares. The project, known as the “Union of Arms”, intended that each kingdom of the Hispanic Monarchy, including the Catalan-Aragonese Confederation, would contribute a determined number of money and soldiers, a burden that until then had fallen mainly on Castile since it had the exclusive monopoly of the American precious metals.

However, the Castilian oligarchies did not gauge well the implications of the oath of the Catalan constitutions. While it granted Philip IV the title of Count of Barcelona, it also restricted his ability to freely dispose of Catalonia’s economic resources. This meant that the monarch needed the consent of the Diputació del General and Les Corts to obtain new taxes or request extraordinary resources, which considerably limited the monarchy’s ability to execute Olivares’ project.

During that visit, the Catalan institutions showed the king more interest in the resolution of grievances that they considered essential than in contributing to military conflicts of exclusively monarchical interest. Among these demands were the demand to block the interference of the Council of Castile in the affairs of the Principality -initiated in the time of Philip II- the protection of Catalan trade, the limitation of the privileges of the Castilian Mesta and other monopolies that benefited Castile to the detriment of Catalonia, as well as measures to protect Mediterranean trade against piracy and French and Genoese competition. Catalonia never refused to defend herself from possible threats, but she rejected a fiscal and military imposition that violated her legal system.

With no clear options on the horizon and excessively conditioned by its international policy, the Hispanic Monarchy ended up imposing a forced militarization and an increase in fiscal pressure -without prior negotiation- with the Catalan institutions, which further fuelled the tension between the central government and Catalonia. This situation of unrest was perceived by the French monarchy as an opportunity to weaken the Hispanic power in the Iberian Peninsula. For decades, France had been looking for fissures in the Hispanic Monarchy,and the situation in Catalonia provided the ideal pretext to intervene.

The opportunity presented itself in 1639 when the Catalan social and institutional crisis became fertile ground for insurrection. France acted with a calculated strategy of destabilization, based on three main axes. First, it offered diplomatic and political support to Catalonia by recognizing its sovereignty under French protection. Second, it intervened militarily in Roussillon and other Catalan areas, reinforcing the perception that France could be an ally against Castile. Finally, it fostered internal division in Catalonia, playing on the rivalry between supporters of resistance and those who saw an alliance with Paris as a viable political option. With these moves, France managed to weaken the Hispanic presence and position itself as a key player in the Catalan conflict.

“The Catalan institutions showed the king more interest in the resolution of grievances that they considered essential than in contributing to military conflicts of exclusively monarchical interest.”

Conflict of identities

Faced with the repression of Philip IV and the centralizing policy of the Habsburgs—led by the Count-Duke of Olivares—Catalonia proclaimed Louis XIII as Count of Barcelona in 1641. This decision implied a reformulation of the Catalan identity discourse, situated between defending its institutions and the necessity of a strategic alliance with France.

However, this connection with France was not homogeneous or without tensions. The French presence in Catalonia did not lead to full integration within the French monarchy, but instead generated discontent among various sectors of society. As French military support transformed into an actual occupation, disenchantment toward France grew, ultimately favouring Catalonia’s return under Castilian sovereignty in 1652.

Oscar Jané Checa’s thesis shows that the redefinition of identities did not only take place in Catalonia, but also in France and Castile. For Castile, Catalonia was becoming – and still is today – a rebellious region that questioned the imperial project of the Habsburgs. For France, northeastern Catalonia was a territory that could become a frontier territory to be administered and assimilated. And Catalonia -as always-was oscillating between the defence of its institutions and the need to fit somehow between one of the two neighbouring monarchies.

At the same time, the financial situation of the Hispanic Monarchy deteriorated. Faced with the inability to meet its debts, the State entered into a cycle of successive bankruptcies (1627, 1647, 1652 and 1662), which undermined its credibility in the eyes of European chancelleries and weakened its international position. On the other hand, France began to apply colbertism, a form of mercantilism that encouraged industry, luxury manufacturing and navigation, making it in a short time the great European economic power of Louis XIV’s time.

A morning on Pheasant Island

On November 7, 1659, Pheasant Island, a small river islet at the mouth of the Bidasoa River between Hendaye and Irún, became the setting for a crucial moment in European history: the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrenees. This agreement ended the long war between the Hispanic and French monarchies, a conflict that began in 1635 as part of the Thirty Years’ War.

Pheasant Island, due to its strategic location as a neutral territory, was chosen for the negotiations. On one side, Luis de Haro, representing a war-weary Hispanic monarchy in decline, and on the other, Jules Mazarin, the powerful prime minister of Louis XIV, advocated for an ascendant France, consolidated as an emerging power in Europe.

France, moreover, arrived with its homework done. For months, the jurist, historian and ecclesiastic Pierre de Marca, royal commissioner, had been working on the delimitation of the new border between the Kingdom of France and the Hispanic Monarchy, especially concerning the incorporation of Roussillon and Cerdanya. His posthumous work, “Marca Hispánica” (1688), became a fundamental reference in the study of the Pyrenean border and the construction of the French territorial identity. Although he was neither a geographer nor a cartographer, his influence on the political configuration of the territory made him a key figure in 17th-century geopolitics.

When the pens met the paper, the cession of several strongholds and territories that reconfigured the political reality of the Iberian Peninsula was confirmed. Castile ceded to France the counties of Roussillon, Conflent, Vallespir and part of Cerdanya, thus consolidating the division of Catalonia. At the same time, the treaty stipulated the marriage of Maria Teresa of Austria, Infanta of Castile, to Louis XIV of France, a dynastic bond that was intended to seal the peace through family union.

While notaries and witnesses were certifying the agreement, celebrations were being prepared in Madrid and Paris. However, for the inhabitants of the affected regions, especially in Catalonia, the signing of this treaty represented a deep wound. And more than forty years would have to pass before the Hispanic Monarchy officially notified the Generalitat of the cession of those territories. The new Pyrenean border represented a definitive cut in the historical territory and at the same time a breach that would ignite, decades later, the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1715). This conflict, with tragic consequences for the Catalan-Aragonese Confederation, would end up establishing the Bourbon model in the Iberian Peninsula, irreversibly altering the political and national balance of the region.

“For Castile, Catalonia was becoming – and still is today – a rebellious region that questioned the imperial project of the Habsburgs. While for France, northeastern Catalonia was a territory that could become a frontier territory that had to be administered and assimilated.”

The economic and institutional fracture of the border

One of the key elements in the integration of Northern Catalonia into the French orbit – apart from the construction of countless forts and fortresses such as Montlluís, Bellegarde, Prats de Molló, Vilafranca del Conflent, Perpinyà, Salsas or Colliure – was taxation, especially through the salt tax, an essential product for preserving food. While in the rest of Catalonia, salt – coming from the mines of Súria and Cardona – continued to be subject to the Hispanic tax system, the new French territories were incorporated into the gabelle regime, a high tax on salt imposed by the French State, which from then on would consume it from the salt mines of Peyriac-de-Mer, Sigean and Gruissan. This change forced the inhabitants of the region to modify their commercial structures and reinforced their economic dependence on the French monarchy.

Consequently, many products that previously circulated freely between the territories north and south of the Pyrenees became subject to taxes and regulations imposed by both monarchies. However, these restrictions generated new commercial dynamics outside state laws. Smuggling became an economic activity of great importance for many border communities, which found in this practice a means of survival and prosperity.

Over the years, this economic fracture was consolidated with a progressive institutional and cultural assimilation. The French administration dismantled the institutions of Roussillon and Cerdanya and progressively imposed the French language in education and official spheres. This process sealed the definitive separation between southern and northern Catalonia, generating a new frontier that transcended geography and became a political and identity fracture that persists today.

A final reflection on the contemporary border

More than three centuries later, the border drawn in the 17th century continues to have significant implications. Northern Catalonia, administratively integrated into the French State, retains cultural and historical traits in common with the rest of the Països Catalans, but its integration into the French Republic has progressively eroded its specificities. The border, which in the past was an administrative and economic barrier, has become today a symbolic separation that marks the distance between two different political and legal realities.

These borders, fixed with the Peace of Westphalia (1648) and reinforced by the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), were conceived as impassable lines in a world dominated by nation states. However, this state model is now in crisis. Globalization, European construction and the claims of national identities question the limits set centuries ago. Alejandre Deulofeu, with his theory of “The Mathematics of History”, stated that empires and nations follow predictable cycles of rise and decline, and that the model built in Westphalia of forced state sovereignties is destined to disappear.

In a European context where borders are constantly being redefined, the European Union has allowed for greater territorial permeability, but identity tensions and struggles for self-determination demonstrate that the border is not only a geographical boundary but also a mutable political and historical construct. Just as the 17th century was decisive for the configuration of the modern nation-state, the 21st century poses new challenges regarding sovereignty, national identities and the role of borders in a changing Europe.

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

The real estate sector is experiencing a sharp drop in sales caused by high-interest rates and difficulty in obtaining credit. François Villeroy de Galhau, governor of the Bank of France, urges commercial banks to make it easier for consumers to borrow.

The rise in interest rates that began more than two years ago across the European Union has had an effect on the real economy, causing European residential real estate investment to fall by 54% in the first nine months of 2023 compared to the previous period, 55% lower than the average of the last five years.

This implosion of the real estate sector has been particularly evident in Europe’s richest countries. In France, the year began with construction of new housing falling to levels not seen since 2010. As wages stagnated, prospective buyers were faced with soaring inflation and increasingly unaffordable mortgages. This translated into a sharp drop in real estate transactions in the first half of 2023, particularly significant (-30%) in the Paris metropolitan area.

The French government and the ECB indicate that, for the time being, there will be no further interest rate hikes. Even so, according to the barometer of the Odoxa Demoscopic Institute, the rise in interest rates, the difficulty in obtaining credit, and concerns about the current international economic situation have caused 38% of French consumers who were considering a real estate project to cancel or postpone it.

This crisis is having a significant impact on the whole real estate sector, which represents 13.3% of France’s GDP. Real estate agencies, construction businesses, developers and, especially, credit intermediaries have experienced an increase in the number of insolvencies that had not been seen for years.

According to data from Altarès, an agency specialising in business information, during the first four months of the year, non-payments by developers have increased by 53.8%, those of construction companies by 55.6% while those of real estate agencies have almost doubled, with an increase of 84% compared to the same period in 2022.

Facilitating access to credit

With interest rates rising from an average of 1.03% in October 2021 to more than 4% in May 2023, and strict regulations on the granting of mortgages, obtaining a loan has become increasingly difficult for consumers looking to buy a home.

The governor of the Bank of France, François Villeroy de Galhau, has taken a stand against investors who expect interest rate cuts in the first half of next year, stating that the ECB is likely to keep them at 4% “at least for the next few meetings and the next few quarters”.

Even so, he urged commercial banks to “play the game”, facilitating lending to consumers, “It is desirable that the supply of bank loans now gradually recovers, but without running the risk of over-indebting households”. Bear in mind that the granting of real estate loans by commercial banks is at historic lows that have not been seen since 2015.

In this context, there has been an average year-on-year fall of 3% in house prices and this trend is expected to continue over the next six months, especially in large urban centres. Eric Allouche, CEO of ERA Immobilier, noted that property price falls are moderate compared to the collapse in sales, but that it is possible that by the end of the year house prices will fall by up to 6%.

Protect yourself from economic crises with the ultimate safe-haven asset: gold. If you want your savings to keep or increase their value, Gold Patrimony.

The largest cumulative banking collapse in modern US history, along with the defeat and subsequent sale of Credit Suisse, represents the worst year for banking since the 2008 financial crisis.

The failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank in March 2023, followed two months later by First Republic Bank, marked the worst US banking crisis in its modern history. The total assets held by the three banks amounted to more than 450bn euros. Adjusted for inflation, this number exceeds the holdings of the 25 banks that collapsed during the 2008 global financial crisis.

The financial markets were panicking, central banks were mobilised, while the US administration called for calm and put in place a series of emergency measures to strengthen confidence in the banking system. To stop the flight of deposits and avoid contagion to other banks, which would have a domino effect, the US regulators launched a one-off initiative to guarantee 100% of deposits.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the pond, Credit Suisse was in free fall. The financial institution’s sharp stock market decline has halved the value of its shares, while the restructuring announced by the bank’s management did not prevent a flight of hundreds of millions of euros in deposits.

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) approved emergency funding of up to 57 billion euros to bolster Credit Suisse’s liquidity amid the banking crisis. A few days later, UBS absorbed its banking counterpart in a rescue operation designed to prevent its demise.

Holding US Treasuries as collateral

A large part of SVB’s business model was based on investing the money of its clients – mostly tech start-ups with a lot of liquidity – in long-term fixed-income deposits. After decades of very low, or even negative, interest rates, it was a very lucrative business. At the end of 2022, this institution had a total of $160 billion in deposits, half of which was invested in US Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities.

In the context of the global crisis and subsequent interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve to combat inflation, the price of money became more expensive and investment was reduced. As a result, many of these start-ups suffered from a lack of funding or wanted to get more return on their deposits. This led many of them to withdraw more funds than the bank had planned, thus forcing the financial institution to sell a large part of these investments in public debt before maturity and at a discount to return the deposits.

Fears that the bank would not have enough cash to return the money to customers who asked for it caused panic and the withdrawal of 41 billion dollars in just one week. The bank sold a bond portfolio valued at 21 billion, just to cover its liquidity, at a loss of 1.8 billion. A rapid deterioration of the bank’s balance sheet led to its collapse.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, certain supervisory rules were relaxed for mid-size banks such as SVB. The regulation under which they were operating did not require them to recognise any of the losses they were taking on those bonds that were dropping in value as rates went up.

In the case of Credit Suisse, and beyond the lack of investor confidence due to the negative figures and doubts about the bank’s funding capacity, the bank had long been in the red due to a string of scandals and a series of fundamental management errors that castrated its ability to recover after the downturn experienced by the investment banking sector in the wake of the health crisis.

Protect yourself from economic crises with the ultimate safe-haven asset: gold. If you want your savings to keep or increase their value, Gold Patrimony.

What many suspected has been confirmed: Black Friday is actually a big marketing campaign. Discounts hardly ever reflect reality and prices on electronics and household appliances are on average 3% higher than the lowest price recorded in the previous 30 days, according to the Organisation of Consumers and Users (OCU).

According to a survey by Tandem Up, 85% of consumers planned to buy something on Black Friday. And the fact is that more and more people are bringing their Christmas shopping forward to take advantage of the supposed sales of this campaign. However, the reality is that the advertised discounts that they found were almost always false, according to a study by the OCU.

This research has compared the evolution of 16,000 online prices over more than a month, mainly for electronics and household appliances, but also in other areas. Its main conclusion is that 99% of the advertised discounts are not real. In fact, the theoretical average discount of 25% labelled for Black Friday turns into an average increase of 3% on the minimum price recorded during the last month.

Non-compliance with regulations

For most products, online retailers do not use the lowest price of the last 30 days as a reference for comparative savings, but any other price recorded during that period or even the recommended retail price, which breaches current legislation.

It should be borne in mind that Law 7/1996 on the Regulation of Retail Trade, recently amended to adapt it to European directives, establishes in article 20.1 that whenever articles are offered with a price reduction “the previous price must be clearly shown together with the reduced price” and that “the previous price shall be understood to be the lowest price that had been applied in the previous 30 days”.

Fortunately, if you think that your rights have been violated, you can file a complaint with the Catalan Consumer Agency, a Municipal Consumer Information Office or one of the Consumer Arbitration Boards.

Catalonia is no exception

Bad practices on Black Friday seem to be widespread if we take into account research on the previous Black Friday campaign in the UK that reaches very similar conclusions to those of the OCU.

After checking 214 offers at seven of the UK’s leading home and technology retailers (Amazon, AO, Argos, Currys, John Lewis, Richer Sounds and Very) during the 2021 Black Friday campaign, it found that 86% of these items had been offered cheaper or at the same price at some point in the six months prior to Black Friday.

It’s clear that Black Friday discount labelling can’t be trusted, so the only alternative, if you’re looking for bargains, is to keep track of price trends for the products you’re interested in. This is the only way to make sure you get them at the right time.

If you want your business to make a giant leap, use 11Onze Business. Our business and freelancer account is now available. Find out more!

Only one in three adult European citizens has a minimum level of financial literacy, according to a new report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This means that most people need to gain the necessary knowledge to manage their money effectively.

Financial literacy is a necessary skill that is essential for everyday citizens. It is difficult to make the right decisions when managing a household, planning savings, applying for credit or taking out a mortgage if we do not have a minimum level of financial literacy.

In this context, and amid the debate on the poor academic results of Catalan students in the fourth year of ESO in the PISA tests, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) presented a devastating report on financial education in Europe. According to this study, only 34% of European adults have a minimum level of financial literacy. Therefore, a large proportion of citizens do not have the necessary skills to manage their finances effectively.

Only Irish and German citizens achieve the minimum financial literacy threshold of 70 out of 100. This is a worrying result given the pressures on household budgets in the current economic climate, which increases the risk of indebtedness and other economic downturns.

Financial literacy at an all-time low

While 84% of adults in the 39 countries participating in the survey understand the definition of inflation, only 63% know how to apply the concept of the time value of money to their savings. Specifically, how inflation impacts the time value of money by reducing the purchasing power of money over time.

Furthermore, although the results show that around 77% of adults understand the relationship between risk and reward, only 42% of respondents across all countries can correctly answer a question about compound interest (interest that is added to the initial principal and on which new interest is generated). Even among adults with savings products in these countries, only 46% understand the concept of compound interest.

The OECD also warns that the spread of digital financial services, which accelerated during the pandemic, makes it more necessary than ever to equip people with the right knowledge and skills to use these products and services safely. Moreover, the introduction of digital currencies and other crypto-assets into the economic ecosystem, which is leading to an increased incidence and complexity of financial fraud and scams, also highlights the need to strengthen the financial literacy of adults to prevent cybercrime.

11Onze’s financial education plan

Empowering citizens through financial education has been at the heart of 11Onze since its inception. Expanding our community’s knowledge of economics and finance, making all the necessary tools available to them, is one of the founding pillars of the first community fintech in Catalonia.

Since the launch of 11Onze Escola, a project that offers training sessions on the world of fintech so that schools, companies and professional associations throughout the country can teach their students the basics of economics and financial matters, we have a unique platform that complements the school curriculum by educating young people in monetary matters and provides them with tools for the creation of wealth.

With the same purpose of training our community, we promote the lessons in the Learning section, which offers content such as the series El Diner, the Formacions 11Onze made by the employees themselves or our short Courses. In addition, in the Descobreix section of 11Onze TV you will also find pieces by our agents on topics of interest for our day-to-day work. Because from the very beginning it was clear to us that without a good financial education, we will hardly be a free society that can decide its future.

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the super app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!