Nine historical disagreements Catalonia-Spain

The economy has been one of the main protagonists in the relationship between Catalonia and Spain. In an exercise of synthesis, we have compiled nine of these key moments in our history. They may not be the best known, but they are undoubtedly the ones that have marked a before and after. One after the other, they offer a chronology of encounters and misunderstandings.

“As long as Spain does not understand the Catalan issue,

Spain will be subjected to the same woes of the past”.

Américo Castro, 1924

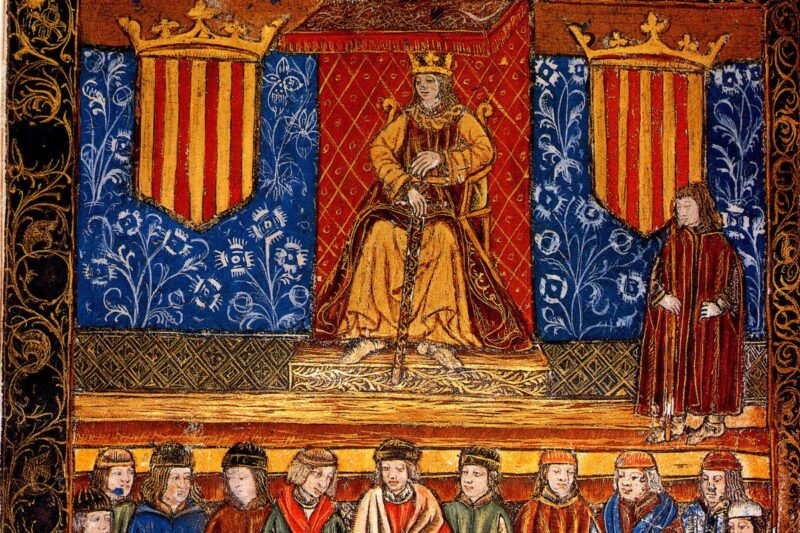

1479. The construction of a dynastic state

After the Castilian Civil War, the two largest kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula (Castile and Catalan Confederation) together created a new political entity known as the Hispanic Monarchy. This dynastic state was formed from the union of just two elements: the army and foreign policy. The other elements that make up a modern state, such as borders, currencies, laws, and institutions, remained completely separate. Thus, with regard to the configuration and distribution of power, it should be borne in mind that, while Castile was organised according to the authority of the queen (Isabella), always above the nobility and the church, the Crown of Aragon was organised around the Constitució de l’Observança, which obliged the king (Ferran) to govern and make agreements in accordance with the laws of the Principality. This is the first difference in the system of political and economic organisation between Spain and Catalonia.

1556. The drift of history

With the death of the Castilian queen (Isabella), the peninsular dynastic state was at the point of dissolving. After family vicissitudes, the throne was eventually occupied by the grandson, due to the incapacity of the daughter (Juana) and the death of the son-in-law (Felipe). The dynastic union between the two kingdoms was thus definitively confirmed in the persons of Carlos (the future emperor) and his successors. For years, Emperor Charles sought to consolidate the idea of a universal monarchy that would be polyglot and open to the entire territory of the Habsburg Empire. The Emperor’s policy was aimed at changing the course of European history. It was of no use for him to believe that it was possible for the rights of cities and regions to coexist with the imperial structure, since the idea of the nation-state was gaining ground, largely as a result of the Reformation. Nor did it ever manage to create the necessary complicity between Castilians and Catalans to forge a common country.

1585. The perversity of the system

In the autumn of 1585, King Felipe II of Castile presided over the celebration of the General Courts of the Catalan Confederation in Monzón. Following the tradition established by his father (Carlos), Felipe II thus recognised the duality of power in the peninsular territory formed by the crowns of Castile and Catalonia Confederation. The parliamentary system always involves tensions – because that’s intrinsic to debating – but it seemed that an agreement would be reached. The problem arose when royal officials tried to blatantly boycott the Cortes‘ resolutions. And it is even more perverse when the Monarchy – unilaterally – decides to manipulate and rewrite the agreements made by the Catalan Cortes to favour its interests. Among the most important alterations, which affected the entire Crown of Aragon, were those relating to the control of trade, the increase in spending by the Royal Court in Catalan territory, and the dilution of the control that the Diputació del General (the Generalitat) could have over the Holy Office (the Inquisition), the repressive arm of the monarchy.

1626. Towards a single centralised unit

In March 1626, Barcelona received the King of Castile, Felipe IV, who had come to the city to swear the Catalan Constitutions. The reason was none other than to unravel the ambitious plan of the king’s minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares. The project, known as the “Unión de Armas”, called for each kingdom that formed part of Castile – that is, mainly the Catalan Confederation – to contribute a certain amount of money and soldiers. But what the Castilian oligarchies did not realise was that if Felipe IV swore to the Catalan Constitutions, he was automatically granted the title of count of Barcelona, which obliged him to oversee their resources. The Catalans were, therefore, more interested in having their proposals for new Catalan Constitutions approved, and their grievances addressed, than in engaging in absurd wars. Curiously, two decades later, the northern Catalan territory would be dishonestly torn away from the main body. And it would not be until forty years later that Castile would officially notify the Generalitat of the loss of the northern Catalan territory.

1760. The rules of the game change

For several decades, a new family of French origin had held the throne of Castile, the Borbones. The open dispute over that ascension had been left behind, to the point that it had had to be settled on the battlefield. Four decades after the Nueva Planta Decree, King Carlos III convened the Cortes Generales in Madrid. In that new political paradigm that emerged from the battlefield, the representatives of the former territories of the Catalan Confederation -formed by Catalonia, Aragon, Valencia and Mallorca- jointly presented a memorial containing a frontal critique of the Borbonic system in force. To put it very simply, the document, known as the “Memorial de greuges”, argued that the new state had to safeguard territorial plurality and move away from centralist and unifying structures.

1810. The construction of a new political reality

In the context of a European war, more than 240 deputies from all over the territory arrived in Cadiz convinced that they were going to make history, to write a Constitution. King Carlos IV of Spain had been deposed as an absolutist, after the French occupation of the peninsular territory. The Cortes of Cádiz established that power resided in the citizens as a whole, represented by the Cortes. But Cadiz was also – for the first time – a real opportunity for Catalan politicians to be invited to participate actively in the new Spanish political system that was being created. In that revolutionary context, the Catalan delegation openly defended the proposal to modernise Spain in accordance with the Austrian project that had been liquidated less than a century before. Therefore, economic and social development had to be based on the industrialisation of the territories. But the Treaty of Valençay restored Fernando VII to the throne as an absolute monarch and frustrated all the modern ideas that had emerged from the Cortes de Cádiz and its revolutionary constitution, which had shaken Spain.

1870. History always gives a second chance

That summer of 1870 in Paris, María Isabel Luisa de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias, Queen of Spain, abdicated. This renunciation of power – like Emperor Carlos – was the consequence of an intense political debate about how Spain’s modernity was to be articulated. The dispute between Carlists and Liberals had been settled on the battlefields for the past three decades. But during the following decades the impasse would continue. Spain had entered a labyrinth from which it would take a hundred years to emerge. Modernity entailed a profound structural transformation, including the distribution of power. Historiography has approached this period from the perspective of the first crisis of Spanish capitalism. But, in reality, at the root of the economic problem was corruption.

Politicians, military officers, and nobles speculated in both the railway companies and in construction, to the point that at the end of the decade there was a stock market crash of biblical proportions. The Civil War in the United States caused an increase in the price of raw materials – cotton – the driving force behind the Catalan textile industry, which – due to a lack of foresight on the part of the state – led to the ruin of many businessmen in this sector. And a prolonged period of poor harvests led to a sharp rise in the price of basic foodstuffs, which had a negative effect on the lower classes. In this difficult context, and given that the state was so heavily in debt, two solutions were found: on the one hand, to increase the tax burden on the working classes and, on the other, to embark on a colonial adventure such as the War of the Chincha Islands off the coast of Peru.

1931. The mountains are a good place to think

That spring of 1931, Spain opted to manage power according to a formula that had failed in the past. Corruption had exhausted the system of the Borbonic Restoration and, therefore, a new relationship with power had to be sought. The question then – and still today – was whether Spain could be a federation of nations. It had to be proved! It was in this context that the deputies of the recently created government of the Generalitat of Catalonia, charged with drafting a proposal for a relationship between Catalonia and Spain, took up residence at the Sanctuary of Nuria. Everyone was certain that this was a historic moment.

The result was a constitutional text that responded to the will of Catalonia and its legitimate right to exercise self-determination. It was proposing a situation of legal and political equality with respect to the other peoples of the State. It was proposing to broaden our outlook. But the state became nervous. A year later, the Spanish Cortes approved a Statute that had nothing to do with the one endorsed months earlier by the people of Catalonia. It rejected the federal formula, reduced the powers of the Generalitat, and established the co-official status of Catalan and Spanish in a bilingual model. Catalonia was reduced to an “autonomous region within the Spanish state”. It was then that sabre rattling began to be heard in the distance, forcing Spain to return to the battlefield.

2004. Towards a new historical paradigm

With the hangover from the events of the last decade of the last century, everyone believed that Spain had chosen to recognise its diversity. The Catalan language was spoken – even – in the most intimate circles of the Castilian oligarchy. In a climate of economic strength, social stability, and mutual recognition, Catalonia believed it could rethink its relationship with Spain. Was it possible? The scrupulousness of the mission – as in the past – in drawing up a new constitutional framework, such as the new Statute of Catalonia, meant a major effort to find a meeting point where all social strata were represented. How this story continues is known to everyone. 1 October 2017 is the confirmation of the impossibility of dialogue and the need to go back to the beginning of everything: much earlier than the Castilian Civil War of 1479.

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the super app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

Un article magnífic, gràcies

Celebrem que t’hagi agradat, moltes gràcies, Manel!!!

Merci per aquesta classe d’història👍

Gràcies a tu, Jordi per llegir-nos i seguir-nos! Seguim a La Plaça!

Gràcies Oriol,com sempre interesant i després d’aquests desencontres,encara es segueix volent l’enteniment amb un estat colonitzador i desposta,hauria de ser d’obligat compliment ensenyar aquests descontres

Certament, estaria molt bé tenir clares aquestes desavinences per part d’una majoria. Gràcies, Alícia. Seguim a La Plaça!

Malgrat aquests incompliments, i com diu la cançó de Lax’n Bustos “Hi Tornarem”

No defallirem mai, fins a la victòria final. Gràcies, Francesc per llegir-nos. Ens veiem per La Plaça!

Bon contingut

Moltes gràcies, Ricard! Celebrem que t’hagi aportat coneixement. Seguim a La Plaça!

Merci Oriol Molt Bon contingut i resum!

Gràcies a tu, Edu! Seguim a La Plaça.

M’agradat molt, encara que per a mi m’agradaria que fos mes extens ja que soc un fanàtic de la Història

Raül, aquesta exposició només ha buscat realitzar una simple síntesi. Gràcies per llegir-nos i seguir-nos. Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Molt enriquidor Oriol, mercès per l’explicació ràpida, practica i entenedora.

Gràcies a tu Ramon! Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Be be

Moltes gràcies, Marc. Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Moltes gràcies, Albert, per aquests petits resums d’història.

Gràcies, Isidre per llegir-nos! Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Per part espanyola, la història sempre es repeteix —és una mena de «dia de la marmota»—; enganys continuats, joc brut, propaganda de les seves mentides, com ara, que Espanya, com a país, comença amb el casament dels Reis Catòlics. Embolica que fa fort: confondre a posta una unió dinàstica amb una unió política. En Ferran II d’Aragó, el Rei Catòlic, era el titular de la Corona d’Aragó, ostentà els títols de comte de Barcelona i de Ribagorça, duc de Montblanc, príncep de Girona, rei de Sicília, rei d’Aragó, rei de València, rei de Mallorca, rei de Castella, rei de Sardenya, rei de Nàpols i rei de Navarra. I la història ho rebla, perquè, en morir Isabel I de Castella l’any 1504, Ferran II d’Aragó marxà de Castella de tornada cap als seus dominis de la corona catalana-aragonesa. Pocs anys després, va ser cridat novament a la Cort castellana per a ser regent de la corona, fins al 1511, que va deixar el tron de Castella en mans del cardenal Cisneros.

Gràcies, Albert! Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Gracies Oriol

Gràcies a tu, Luis Miguel. Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Hola Oriol, amb trec el barret, ho he llegit i sentit de d’altres maneres, però mai tant clar i senzill com ho has fet tu, les meves felicitacions.

Gràcies, Ramon! Tot és mèrit de la comunitat. Ens veiem per La Plaça.

I despres de mes de 600 anys continuen sent la pedra al nostre cami, i si fem com diu la canço, i la fem tombar?!!!

Esther, crec que arriba l’hora de decidir que volem ser de grans. Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Excel·lent expossició.

Moltes gràcies, salut i força al canut!

Gràcies, David! Seguirem fins al final. Seguim a La Plaça.

Uauuu!!!! Oriol quin èxit la teva sintetització històrica 🙏🙏

Ha estat un exercici interessant de fer, Laura! Gràcies per llegir-nos. Seguim a La Plaça.

Gràcies per un exercici de síntesi tant encertat. Ara ens toca a nosaltres aprofondir des d’aquestes bases excel·lents!

Gràcies a tu Guillem per seguir-nos i llegir-nos. Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Spain is Spain…

Cert, Xavier! Ens veiem a La Plaça!

Gràcies pel repàs històric Oriol!

Gràcies a tu Miquel per seguir.-nos i llegir-nos. Ens veiem per La Plaça!

Conèixer la història per entendre el present i enfocar el futur. Bon article

El mestre F. Braudel ja ens ho ensenyar. La llarga, mitja i curta durada del temps històric és bàsic per entendre el passat, per no caure en els mateixos errors i projectar correctament el futur. Gràcies per seguir-nos i ens veiem per La Plaça.

👏👏👏👏

Gràcies, Josep. Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Una gran lliçó que ens ajuda a ser menys ignorants.

“Tornarem a sofrir, tornarem a lluitar, tornarem a vèncer”. Carles, el president Companys ja ens ho va advertir. Gràcies i ens veiem per La Plaça.

Molt interesant m’ encanta la història.

Dos ja en som dos, Rosa. Seguim a La Plaça.

Gràcies, Rosa Maria. Anem aprenent tots plegats.

Moltes gràcies Oriol! M’ha encantat aquesta cronologia, és una molt bona perspectiva històrica! Fets tan llunyans i tan presents, alhora….Espero que algun dia n’aprenguem!

La memòria del passat és fonamental per a construir un futur millor. Gràcies per seguir-nos i ens veiem per La Plaça amb futures aportacions.

Cristina, l’Oriol sempre ens dona una perspectiva diferent i útil molt entenedora. Gràcies.

No fotem, tanta perserverància ens ha de servir alguna vegada a la història no? cullons visca Catalunya lliure!

Miquel: “We shall never surrender”, Juny de 1940 W. Churchill.

Gràcies, Miquel. La veritat és que la perseverança sempre serveix en tots els propòsits que ens fem a la vida, i si l’acompanyes de il.lusió la cosa encara funciona millor.

Com sempre estructurat,ben explicat,i fas que escoltar i llegir et facin quedar amb les ganes de saber més

Gràcies Oriol

Gràcies, Alícia. Aportar coneixement a la comunitat és fonamental per fomentar l’esperit crític. Ens veiem a La Plaça.

Gràcies, Alícia, tens tota la raó.

Gràcies, Albert! Seguim a La Plaça.

Interessant article i molt ben explicat, Oriol.

Gràcies, Xavier. Ens veiem per La Plaça!

Com sempre Oriol. Impecable

Gràcies, James!

👍

Gràcies, Joan! Ens veiem per La Plaça!