Does the Constitution explain what Spain is?

For some time now, history has brought us back to an old and still unresolved debate: what exactly is Spain? A difficult question that a handful of generations have had to face. Along the way there have been all sorts of debates, promises, triumphs, and defeats. And, in spite of everything, we are still far from finding an answer.

After Franco’s long night, Spain was faced with new challenges from 1975 onwards. The state had to strike a balance between the reform proposed by Franco’s government and the rupture demanded by the opposition. The agreed solution was to move together towards a new regime based on a new Magna Carta. The Spanish Constitution of 1978 was divided into ten titles and 169 articles. In the text, the term “nation” appears only twice, while the term “State” contains 90 entries.

The first and most important mention of “nation” is the one that opens the Preamble. “The Spanish nation, desiring to establish justice, liberty, and security and to promote the good of all its members, in the use of its sovereignty…,” the founding text begins, as if the nation itself were writing the text that will be read. Further on, this self-proclaimed “nation” expresses the will to “constitute itself as a social and democratic state governed by the rule of law,” which will deploy all its organs and functions.

The “nation,” the subject of dispute

The reference to “all its members” seems to refer to individuals. Indeed, Article 2 bases the Constitution on “the indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation, the common and indivisible homeland of all Spaniards,” which “recognises and guarantees the right to autonomy of the nationalities and regions that make it up and the solidarity between all of them.” It is precisely this article that is the subject of continuous litigation.

This famous article 2, in reality, seems to be telling us that it is not the individuals who decide or want something, but the nation. For it is the nation that holds sovereignty, not the people. And the one who makes this proclamation of sovereignty is not the people either, but is personified in the figure of the King of Spain. Therefore, everything that makes up the nation is confusing.

“Seems to be telling us that it is not the individuals who decide or want something, but the nation. For it is the nation that holds sovereignty, not the people.”

The kingdom of “nationalities”

Certainly, the allusion to nationalities and regions points to the old idea of the territorial division of the kingdom. This word —“kingdom”— is nowhere mentioned in the Constitution. A strange thing, given that Spain is configured, in its form, as a kingdom. Kingdom of Spain, in the singular. But then, what are nationalities and what does the term hide to refer to these ethno-cultural organic entities?

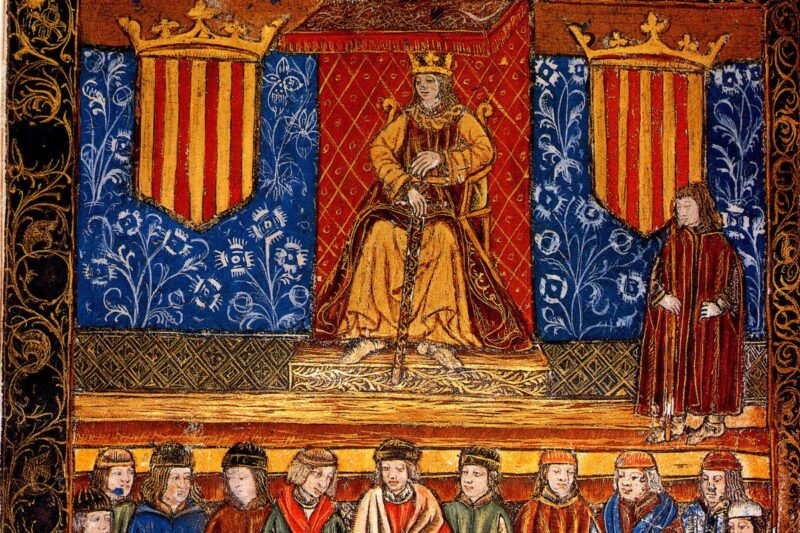

It seems evident that it is a pious expedient to allude, without naming them, to the ancient kingdoms of Hispania, in addition to Castile, formed by: Catalonia, Valencia, Majorca, Aragon, Navarre, Galicia, the Basque Country, Andalusia (and Portugal). So what is the meaning and function of nationalities and regions? It is impossible to know, since these concepts do not appear again in the Constitution.

Everything revolves around the “reconquest”

Contrary to the discourse repeated like a mantra within the Francoist school system, learning about Spain was articulated around the concept of the “reconquest.” This is a historiographical term – still used in secondary school curricula in Castile – which describes the process of recovery of the feudal world over the Muslim and Jewish world, because it is understood that the Muslims were not the legitimate owners of the Hispanic geography…

This process began shortly after the arrival of the Arabs on the Iberian Peninsula in the 8th century and ended with the Catholic Monarchs in the 15th century, who would end up unifying “Spain” as an integral state. This reconquest would end up forging “the Spanish spirit.” In other words, historical arguments to justify the National Catholicism imposed after the Civil War.

Even so, it does not seem that there has ever existed ‘de facto’ a “Spanish nation,” that is, integrating nationalities and regions, as the current Constitution would have us believe. It is not even certain that it has ever been consolidated as a nation-state, in the modern sense. We see it below!

“It does not seem that there has ever existed ‘de facto’ a ‘Spanish nation’, that is to say, integrating nationalities and regions, as the current Constitution would have us believe.”

From confederation to absolutism

The dynastic state, initiated by the Catholic Monarchs, as we have stated, ended up becoming an absolutist state. Before becoming an absolutist state, it had to restrict the power of the nobility, force adherence to the Catholic religion and unite all power in a loyal devotion to the King. Contrary to what some think, the language remained outside this power scheme. Therefore, it was never a unifying element until the beginning of the 18th century, although Francoism tried to falsify history once again.

Power was organised around five Councils of State: Castile, Aragon, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal (1580-1640) and the West Indies. Therefore, the different territories that made up the geography of the Corona de Hispaniae —plural of Hispania— maintained their own administration, currency, and laws. In this sense, it was a kind of confederation of nationalities, which retained their own peculiarities, charters, and traditions.

The predominance of Castile (which included Galicia, Asturias, and León) over the other existing kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula became increasingly evident, in terms of extension and population and, above all, after incorporating the West Indies into the Castilian kingdom, which did so by way of “discovery,” with all that this entailed. Thus, the progressive transfer of the economy from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic brought about a paradigm shift in relations between the different territories that made up the Hispanic Crown.

This plurality, which was not without its ups and downs, gradually led to a greater centralisation of power. But the definitive leap came after the War of Succession and the subsequent enthronement of the Bourbon dynasty on the Castilian throne. Between 1707 and 1716, the new King Felipe V promulgated the well-known Nueva Planta Decrees throughout the different territories of the Crown of Aragon as punishment for their rebellion and as a right of conquest. However, this loss of autonomy never affected Navarre or the Basque Provinces, since these territories had been loyal to the Bourbon cause.

It was then that Castile was transformed into Bourbon Spain: an absolute and highly centralised monarchy. As proof of this process, Felipe V wrote in 1717: “I have judged it convenient […] to reduce all my Kingdoms of Spain to the uniformity of the same laws, customs, habits, customs and courts, all governed equally by the laws of Castile.” Thus, as a result of repression and by right of conquest, a forcibly Castilianised Spain began to take shape as a modern (French-imported) national (Castilian-exported) state. Naturally, the illusion was short-lived.

“Of the nine contemporary Spanish constitutions, all of them have in common the same affirmation: they are a constitution of the monarchy and of Catholic confession.”

The failed illusion of the “federative republic”

The enlightened writer José Marchena (1769-1821), exiled in Bayonne to escape the Inquisition, wrote a revealing report in 1792 for Jacques Pierre Brissot, a Girondin and foreign minister of the French Republic, on the difficulties of implementing in Spain a constitution similar to the French one of 1791. His words are quite revealing: “France has now adopted a constitution which makes of this vast nation a united and indivisible republic. But in Spain, the various provinces of which have very different customs and usages, and to which Portugal must be united, it should only be possible to form a federative republic.”

In a similar vein, in 1808, in Cadiz, the famous politician from Girona, Antonio de Campmany wrote, just after the French War had begun, in the famous publication ‘El Sentinella’: “…. In France, then, there are no provinces or nations; no Provence or Provençals; no Normandy or Normans. They have all been wiped off the map of their territories and even their names […]. They are all called French.” And he goes on to say: “So what would become of the Spanish if there had not been Aragonese, Valencians, Murcians, Andalusians, Asturians, Galicians, Extremadurians, Catalans, Castilians? Each of these names inflames the pride of these small nations, which make up the great nation.”

Decade after decade, of the nine Spanish constitutions drafted during the contemporary age (1812-1978), all have in common —with minor nuances— the same affirmation: they are a constitution of the monarchy and of Catholic confession, the religion of the King and of the nation. Therefore, the unity of the nation is the unity of the monarchy.

Does it exist, then, a nation of nations?

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

👍

Espanya és una unió forçada de regnes i estats mal avinguts.

Gran aportació! Seguim a La Plaça!

Fa un any mentre llegia aquest article m’anava enrabiant.

Avui l’he gaudit. El problema s’agreuja, però hi ha gent com l’Oriol que es creuen el

#seguim i actuen en conseqüència. Hi afeigexo #fent.

Gràcies Oriol, gràcies 11Onze, gràcies La Plaça.

Seguim al mateix punt on ho vàrem deixar ara fa un any! Hem de superar l’adormida que ens han imposat. Sense aquest pas, mai assolirem l’objectiu final. Gràcies, Mercè. Seguim a La Plaça!

Molt Interessant.

D’això es tracta, Joaquin d’aportar valor i coneixement a la comunitat! Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Moltes gràcies, Joaquim!!!

Bona feina, Oriol, gràcies

Gràcies, Guillem! Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Et felicito Oriol,es brillant i encertada aquesta conclusió de “totes les constitucions espanyoles són del rei i la religió

Extraordinari

Gràcies, Alícia per llegir-nos i seguir-nos. Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Paper mullat

Totalment d’acord, Ricard! Seguim a La Plaça!

Quan una constitució s’imposa per la força a uns quants, és esperable que aquests darrers com que es poden sentir sotmesos es rebel·lin.

Cert, Francesc! Cal construir una nova realitat històrica ràpidament. Ens veiem per La Plaça.

Totalment d´acord Francesc. Seguim endavant!

Molt bé nois! 👌👌

Moltes gràcies, Joan! Seguim a La Plaça!

👍

Moltes gràcies, Joan! Ens veiem a La Plaça!

👍 Ok

Moltes gràcies, Josep! Ens veiem a La Plaça!

A l´hora de redactar les constitucions quan la batuta la porta el que guanya les guerres no se’n pot esperar res de bo, tant si el vencedor és un regne com una república. Les nacionalitats van surgir per descafeinar les nacions, que són les que poden aplicar l’autodeterminació, i per descomptat els vençuts ho van acceptar, presentant-ho com un triomf. El redactat és important. Podem analitzar el que sigui, tenint sempre present l’article 2 “La indisoluble unidad de la nación española, patria común y indivisible de todos los españoles”.

La constitució del 78 es hereva dels usos i costums de les relacions Castella-Catalunya durant 500 anys, on hi ha una nació, Castella, que és qui mana, i una altra que creu, Catalunya.

El gener del 39 Franco va entrar a Barcelona com Ejército de Ocupación, no de Liberación ,no ho oblidem. Es la clau de moltes coses.

Oriol, molt bé que expliquis el perquè els bascos i els navarresos gaudeixen de privilegis especials, Els del bàndol dels vencedors sempre hi guanyen. Vol dir doncs, que la guerra de Successió encara influeix molt a Espanya.

Penso que molts pocs n’estan al cas.

Gràcies per l’article, ens fa molta falta saber perquè som on som.

I el problema de tot plegat és que ens van explicar fins a l’avorriment que la TRANSICIÓ havia estat MODÈLICA. I resulta que l’Estat fa aigües per tot arreu. Cal aprofitar l’oportunitat que se’ns presenta, Mercè. Seguim a La Plaça.

👏🏿👏🏿 Oriol

Thanks, James.

Brillant exposició! “la unitat de la nació és la unitat de la monarquia” Una nació de nacions, molt d’acord. Gràcies, Oriol!

Gràcies per seguir-nos i llegir-nos, Anna!