Two women ignored by history books

Throughout our education we have learnt great people that have marked history by their findings or research. The vast majority of them are the names of men who have achieved success. What the books do not tell you is that many of these men have worked together with women, without whom their achievements would not have been possible.

In all sectors of work we find women who have been made invisible simply because they are women. In many cases, their work has even been attributed to the figure of a man who has received all the recognition, and the world of economics is no exception. We want to shine a light on these women who have been left in the shadows and vindicate their contribution to history.

Beatrice Webb, revolutionary ideas

From an early age, Beatrice had many intellectual interests and was very interested in socialist ideas as a result of the revolutionary ideas that were current at the time. She was born in 1858 in Gloucester, England, a time when the working class of the Industrial Revolution suffered indiscriminate exploitation by the bosses and families lived in misery. Driven by this context and her delicate health, Beatrice undertook a practically self-taught education with a strong focus on philosophy, science and literature.

In 1890 she met the socialist intellectual Sidney Webb, who later became her husband. Together they began to work on new theories by holding meetings with other socialist sympathisers where they would argue for hours on different subjects. In 1897 they published what was to be the most important work of their lives and a key instrument for understanding the non-Marxist socialist revolution in England, “Industrial Democracy”.

They are credited with the idea of a state guaranteeing a decent life for its citizens, a term she herself called the house-keeping state. Although they formed a perfect tandem and worked together on different publications, only the name of her husband, Sydney Webb, went down in history as one of the most important social reformers in England.

Anna Schwartz, essential to monetarist theory

If we mention the name Friedman, it is likely that we have heard of him or even recognise him as the father of monetarist theory. And he certainly contributed to the creation of his reputation, but he was helped by Anna Schwartz, a researcher who remained in the shadow of Friedman’s prestige.

Born in New York in 1915, she spent much of her life working at the National Bureau of Economic Research in her native city. In 1963, however, her career took a leap forward with the publication of “A Monetary History of the United States, 1867 to 1960’, a work that came to light thanks to the joint research of Schwartz and Milton Friedman. The work marked the history of the US economy and is still today a benchmark for good economic management and how to avoid fluctuations at the national level.

Friedman was named as the founding father of monetarist theory, relegating Schwartz to second place. In 1976 she received the Nobel Prize in Economics for her work with Schwartz, but she received no mention in the committee or in the public sphere. Years later, British critics highlighted Schwartz’s research, claiming its importance in the development of the theory, but she did not receive recognition.

They are just two examples of women who have contributed to history but who, because they are women, have been relegated to the background, to the shadows. Now, with more resources than before and a more critical eye, we can dust off those figures who, despite having made their contribution, have been excluded from the history books.

11Onze is becoming a phenomenon as the first Fintech community in Catalonia. Now, it releases the first version of El Canut, the super app of 11Onze, for Android and Apple. El Canut, the first universal account can be opened in Catalan territory.

A mesura que el segle XXI ha deixat enrere el bel·ligerant segle XX, el sistema econòmic s’ha anat fent cada vegada més complex. Pel camí, algunes crisis han estat terriblement violentes i de conseqüències devastadores; altres, anecdòtiques. Finalitzem aquesta radiografia sobre les grans crisis de la història de la humanitat.

Malgrat que el segle XX és un segle curt, les seves conseqüències afecten encara el nostre dia a dia. La historiografia considera que el seu arc cronològic va des del final de la Primera Guerra Mundial (1918) fins a la caiguda del mur de Berlín (1989), tot i que es podria allargar fins a l’atac de les torres bessones de Nova York (2001). La intensitat dels esdeveniments és de tal magnitud que ens obliga a reflexionar cap on anem. Per això, el segle XXI l’hem iniciat amb un munt de preguntes transcendentals a respondre: la crisi climàtica, el model productiu, el consum, l’habitatge, la relació amb els diners, la tecnologia, la llibertat… Sabrem trobar respostes que beneficiïn el conjunt de les societats?

1929: El megacrac

Hi ha fets històrics… i després hi ha EL FET històric. I, per al món contemporani, aquest l’és. És la frontissa que marca un abans i un després. Una concatenació de decisions polítiques, econòmiques i socials que acabarien portant el món a l’abisme. Les seves causes i conseqüències han estat estudiades per totes les disciplines de les ciències socials. I, encara avui, es pren com la referència per definir si una crisi econòmica tindrà un impacte més o menys gran. Parlem del crac borsari americà de l’octubre de 1929.

L’economia americana de principis dels anys 20 del segle XX es va assentar seguint un esquema purament especulatiu, la qual cosa va provocar un important desfasament entre l’economia real i l’activitat borsària, que s’aniria agreujant i agreujant cada cop més.

Davant del tancament dels mercats europeus i del descens dels preus agraris, el govern americà i els bancs van intentar contrarestar-ho amb l’oferta d’un volum considerable de crèdits. Aquestes mesures van donar lloc a una gran abundància de capitals a curt termini i a l’especulació, especialment a partir del 1926. Per a més desgràcia, les autoritats monetàries no van actuar a temps per posar fre a aquest lucre malaltís.

Així va ser que, en començar l’octubre del 1929, es van produir tendències a l’alça de les inversions. Però quan la venda d’accions es va disparar, el 24 d’octubre es va desfermar el pànic, i el mateix va succeir el dimarts 29 d’octubre. La caiguda de la borsa va ser inevitable a causa de la nul·la demanda d’accions i es va desencadenar una crisi global de dimensions bíbliques. Apocalíptica. Molt pitjor que la crisi anglesa de 1720, atès que va afectar el món sencer.

Fins al 1932, uns 5.096 bancs es van declarar en suspensió de pagaments. El seu esfondrament va arrossegar a la fallida moltes empreses, que veien com s’acumulaven els estocs de mercaderies, cosa que va comportar un important descens dels preus, especialment en el sector agrari. Finalment, el descens de l’activitat econòmica va provocar un augment desbocat de l’atur.

Per frenar l’hemorràgia del sistema financer, a partir de 1931, la repatriació massiva de capitals nord-americans d’Europa —que havien ajudat a finançar la postguerra de la Primera Guerra Mundial— va provocar les fallides dels bancs europeus, principalment austríacs i alemanys. A partir d’aquí, la història és coneguda. El món sencer es veié abocat a una llarga nit apocalíptica.

“El crac borsari americà de l’octubre del 1929 és la frontissa que marca un abans i un després. Encara avui, es pren com la referència per definir si una crisi econòmica tindrà un impacte més o menys gran”

1945: Després de l’Apocalipsi

60 milions de morts. Aquest és el cost total en vides que va haver de pagar la humanitat per la Segona Guerra Mundial. La destrucció de ciutats, pobles, infraestructures, paisatges, béns materials, indústria… fou gegantí. Descomunal. La despesa econòmica ha estat xifrada en 200.000 milions de dòlars del 1947, la qual cosa equivaldria actualment a uns tres bilions de dòlars. La devastació d’Europa i parts de l’extrem asiàtic, com ara el Japó, va ser de tal magnitud que el món sencer va experimentar una profunda i dolorosa postguerra. Calia començar a escriure la història de nou amb urgència. Però, quines opcions hi havia?

Igual que havia succeït en el passat en la resolució de conflictes bèl·lics, com ara al Congrés de Viena per redibuixar el mapa d’Europa després de la derrota napoleònica o al Tractat de Versalles després de la Primera Guerra Mundial, la trobada entre vencedors era un fet imminent. Calia projectar el futur i, per aquest motiu, els aliats es van reunir a la ciutat alemanya de Potsdam, l’estiu de 1945.

Els acords van tenir una resolució relativa, perquè es van anar configurant en les següents dècades. Tanmateix, els vencedors van actuar més com a notaris de la nova situació geopolítica que no pas com a cervells de la nova reordenació mundial. Per tant, la Conferència de Potsdam va visualitzar amb claredat la divisió del món en dos blocs. Dos models polítics, socials i econòmics que provocarien diversos conflictes armats de baixa intensitat al llarg de les següents quatre dècades.

L’avenç tecnològic que va suposar la Segona Guerra Mundial portaria la humanitat a sortir a l’espai exterior, a la Lluna i més enllà, però també va suposar el desenvolupament de la bomba atòmica com a arma de destrucció massiva. Aquesta amenaça ha estat emprada des d’aleshores com a instrument de pressió política.

1973: Si jugues amb foc, et pots cremar

Acabada la Segona Guerra Mundial, el model de creixement que va adoptar el món occidental, inclòs el Japó, es va basar en el consum massiu de petroli. D’aleshores ençà, l’economia d’Occident ha tingut una forta dependència d’aquest recurs limitat. I és ben sabut que, si vols que la teva economia funcioni correctament, has de saber quines són les teves amistats i ser conseqüent amb els teus actes.

El 6 d’octubre de 1973, el dia del Iom Kippur o Dia de l’Expiació del Pecat, la festivitat més important pels jueus, tropes d’Egipte i de Síria van llançar una gran ofensiva contra Israel per tal recuperar el Sinaí i els Alts del Golan perduts el 1967. Després de tres setmanes de combats, els israelians, amb el suport dels Estats Units, van aconseguir restablir la seva hegemonia a la zona.

Aleshores, els països àrabs de l’OPEP, és a dir, els que controlaven el petroli, no contents amb la situació, van decidir embargar el petroli a tots els països occidentals com a represàlia vers els qui havien donat suport al conflicte. La mesura va provocar un increment desorbitat del preu del petroli —es va passar de pagar 2,90 dòlars a 11,90— cosa que va provocar un fort augment de la inflació a escala mundial.

Per a l’economia nord-americana, principal motor econòmic d’Occident, l’embargament va suposar una desacceleració dràstica de l’economia, amb el consegüent augment de l’atur. De fet, ja feia mesos que el mercat havia començat a mostrar símptomes preocupants de desacceleració, als quals se sumava la decisió del president Nixon de deslligar el dòlar del patró or. Així va ser com, amb la fi del sistema pactat en els acords de Bretton Woods, es va abocar l’economia a l’abisme.

L’embargament va durar sis mesos i va generar importants problemes de subministrament energètic, així com una etapa de baix creixement econòmic generalitzat a escala mundial. Alguns països, com França, van buscar altres fonts energètiques, com l’energia nuclear, mentre que els Estats Units i el Canadà van optar per la crema de residus de fusta.

Precisament, el nostre present ens obliga a plantejar-nos si aquest model de consum energètic desbocat, que ha estat durant dècades la principal font de creixement per al món occidental, es pot continuar mantenint. La crisi climàtica és una realitat ben palpable i cal treballar de valent per trobar solucions reals que promoguin un canvi de model productiu i de consum molt més sostenible.

“El nostre present ens obliga a plantejar-nos si aquest model de consum energètic desbocat, que ha estat durant dècades la principal font de creixement per al món occidental, es pot continuar mantenint. La crisi climàtica és una realitat ben palpable”

1988: El sistema va col·lapsar

Si volien sobreviure, havien de fer un pas endavant. Per no col·lapsar, calia fer una reforma molt rellevant, i mil·limètricament calculada, del sistema implementat el 1917. L’encarregat de dur a terme aquest repte gegantí va ser un jove advocat, escollit primer secretari del Partit Comunista tres anys abans, i sobre el qual la vella guàrdia tenia dipositades totes les esperances. A principis de la dècada dels 80 del segle XX, l’URSS estava davant d’una cruïlla històrica important. Com era possible que, essent la segona potència industrial del món, no fos capaç de produir prou béns de consum i aliments per satisfer les necessitats de la seva població?

La situació s’havia fet més que evident a partir dels 70, quan el sistema soviètic s’havia mostrat ineficaç pel que feia a planificació central. I a això s’hi sumava el pes descomunal de la despesa militar, un endarreriment tecnològic brutal i una deficient qualitat del treball a causa d’una mà d’obra desmotivada. A més, tot això era gestionat per un partit únic conformat per velles glòries!

Les reformes econòmiques i polítiques promogudes a partir del 1988 pel primer secretari del Partit Comunista rus, Mikhaïl Gorbatxov, anaven encaminades a reajustar el sistema sense destruir-lo. Aquest reajustament implicava una liberalització del mercat i una obertura del comerç exterior. No obstant això, tard o d’hora, se sabia que ambdues opcions desembocarien en una democratització de la societat. L’acceptació explícita de la transició d’una economia centralitzada i planificada cap a l’economia de mercat posava fi a més de 70 anys d’experiment soviètic, iniciat en aquella llunyana Revolució d’Octubre del 1917.

Malgrat totes les mesures dutes a terme, la Perestroika va fracassar. El debilitament del poder central, la reactivació dels nacionalismes i l’aparició d’importants conflictes interns va accelerar el final de la Unió de Repúbliques Socialistes Soviètiques en menys de tres anys. Després d’això, li va seguir un període de fortes crisis als antics territoris de l’URSS, molts dels quals encara perduren avui en dia, com demostra el que passa a Ucraïna, on es barregen motius històrics i interessos geopolítics derivats de la guerra freda.

2001: ‘Corralito’, quan els diners es van volatilitzar

I van voler tocar el cel. A principis dels 90, l’Argentina havia posat en marxa el Pla de Convertibilitat, que consistia a mantenir un canvi fix d’un peso per un dòlar (1:1). Aquesta mesura pretenia acabar amb la hiperinflació i estabilitzar els preus a través del creixement econòmic. D’aquesta manera, es buscava reduir el dèficit fiscal després d’un període de recessió amb el consegüent endeutament de l’Estat.

A principis del 2000, el deute extern argentí provocat per la convertibilitat va començar a ser cada vegada més important, cosa que va propiciar un augment exponencial del dèficit fiscal. Tot plegat, va començar a generar desconfiança entre els inversors, tant interns com externs, que, moguts pel rumor d’una possible suspensió de pagaments de l’Estat, van iniciar una fugida massiva de capitals.

El drama de tot plegat va començar un fatídic 3 de desembre de 2001, quan l’Argentina es va enfrontar a una limitació de la llibertat dels titulars dels comptes per disposar de diners en efectiu dipositats a les entitats bancàries. Aquest ‘corralito’ va ser decretat pel president de la República per estabilitzar l’economia, la qual cosa va provocar l’efecte contrari.

Què havia fet l’Estat davant d’una situació extrema? Doncs demanar un préstec de 40.000 milions de dòlars al Fons Monetari Internacional (FMI) l’any 2000. I quan se li van acabar, què va fer? Doncs tornar a demanar un altre préstec de 30.000 milions de dòlars a l’FMI el 2001. D’aquesta manera, el novembre del 2001, el deute públic de la República Argentina es va situar a prop dels 145.000 milions de dòlars. O sigui, un 150% del seu PIB. Per tenir una equivalència i ser conscients de la magnitud de la tragèdia, les economies occidentals d’aquell període estaven a prop del 50% d’endeutament del seu PIB. Un any més tard, l’Argentina abandonava la convertibilitat [1:1,45], devaluava la seva moneda i es declarava en bancarrota.

La taxa d’atur s’havia situat a prop del 35%, la prima de risc s’elevà per sobre dels 5.000 punts, la inflació se situà en el 52% i el 60% de la població esdevindria pobre en els següents anys. Davant d’aquesta situació tan dramàtica, esclataren importants aldarulls a les principals ciutats argentines. I quina va ser la reacció de l’Estat? Una contundent i indiscriminada repressió. Les seqüeles d’aquella crisi perduren en la societat argentina i la por d’un altre ‘corralito’ continua existint en la seva memòria. Es calcula que en 11 mesos, quasi 25.000 milions es van volatilitzar. El 2010, Grècia va viure una situació similar al ‘corralito’ d’Argentina.

“A partir del 2008, la realitat va ser una altra: un veritable desastre. El sistema financer havia desenvolupat i comercialitzat productes com les hipoteques ‘subprime’, les preferents o els futurs, i acabaria engolit per la seva cobdícia”

2008: Una hipoteca dona tant?

Segur que aquesta història et sona: “Tenia un piset que em van deixar els meus pares en herència. El vaig vendre. Amb l’import obtingut, vaig comprar un terreny que vaig hipotecar per construir la casa dels meus somnis, perquè sempre havia volgut viure fora de la ciutat. D’aquesta operació financera em van quedar uns estalvis.

Un bon dia, vaig rebre la trucada del meu assessor, el del banc de tota la vida, el qual m’oferia invertir els meus estalvis en la promoció d’una luxosa urbanització de cases unifamiliars a prop del mar. Semblava una inversió segura. Com que estava avalada pel mateix banc, hi vaig confiar. Llavors, el meu assessor em va comentar, sense estar signat enlloc, que amb aquesta operació podria viure despreocupadament dels diners la resta de la meva vida.

Aleshores, va ser quan em vaig engrescar. Per la confiança que em generava l’operació, per la gestió personalitzada de tants anys plegats i, per dir-ho clar i català, per guanyar més diners, vaig sumar als estalvis una ampliació de la hipoteca de la casa. També vaig demanar una mica més per construir-me una piscina, renovar-me el cotxe i, fins i tot, vaig anar de vacances a les Illes Fiji.

Però un dilluns fatídic em va trucar l’assessor per comentar-me que la promoció havia estat un fracàs i que, per tant, ho havia perdut tot. A partir d’aquell moment, la quota mensual de la meva hipoteca se’m va incrementar un 800%”.

Aquesta va ser la il·lusió amb què el sistema financer, encapçalat principalment pels bancs, va fer creure a molta gent que era possible viure en un món feliç. Tanmateix, a partir del 2008, la realitat va ser una altra: un veritable desastre que, sumat a altres productes que el sistema financer va desenvolupar i comercialitzar, com les hipoteques ‘subprime’, les preferents o els futurs, acabaria engolint la cobdícia d’aquest mateix sistema.

Infinitat d’estudis, articles, entrevistes, reportatges, documentals o pel·lícules han explicat fins a l’avorriment la crisi financera global del 2008, que va tenir el seu origen en la comercialització d’un conjunt de bons d’habitatges col·locats al mercat pels principals bancs als Estats Units. En un principi, aquests bons immobiliaris oferien a l’inversor un alt rendiment amb un risc baix. Aviat, això va propiciar que aquests productes es convertissin en l’instrument de moda i els preferits pels bancs.

Els bons estaven sustentats per un conjunt d’habitatges hipotecats, amb pagaments regulars al corrent per part dels propietaris. En aquesta fase, la taxa d’interès es mantenia baixa. Fins aquí, un producte normal del 2000 que oferien els bancs. Però la cosa va començar a canviar a partir del 2006, quan algun espavilat va trobar la manera de mantenir el flux constant de capital que aquests bons generaven.

Per tant, la clau de volta radicava en ampliar el mercat i començar a oferir crèdits hipotecaris a tort i a dret, sense comprovar ni ingressos regulars ni l’historial creditici de qui l’anava a adquirir. Segurament, l’espavilat d’abans ja sabia que això tenia un límit, perquè les cases són finites i els pagadors regulars, també. Perquè, què passa quan un no paga? El sistema ho pot assumir. I què passa quan dos no paguen? El sistema encara pot assumir-ho. I què passa quan molts no paguen? Aquí és quan apareix el problema. Tot s’esfondra. La resta és sabut.

A mitjans dels anys 80, l’economia japonesa ja havia passat per un procés similar de revalorització d’actius financers i immobiliaris, que els experts havien considerat com una de les majors bombolles especulatives de la història moderna. El 2006 ningú va mirar al passat. Només uns pocs se’n van adonar. Si t’interessa saber com s’ho van fer, no et pots perdre la pel·lícula ‘The Big Short’ (2015).

“Serà de vital importància preparar-se, construir una cultura financera sòlida, en comunitat i amb llibertat, per no tornar a caure en l’abisme, pel que vindrà”

2022: Cap a una simbiosi amigable

Potser va ser massa agosarat i el temps ha demostrat que es va equivocar. Va ser en el context de la caiguda del mur de Berlín, l’any 1989, quan el politòleg nord-americà Francis Fukuyama va publicar el seu cèlebre i polèmic article sobre “el final de la història”.

La tesi plantejava que, amb el final de la guerra freda, la història havia arribat a la seva fi, perquè s’havia arribat a una uniformitat ideològica global. Aquesta afirmació se sustentava sobre la idea que havia estat la democràcia liberal, representada pel capitalisme occidental, la que havia estat capaç de fer caure el comunisme del bloc soviètic i, per tant, seria capaç de frenar en el futur altres guerres i revolucions. Però realment la història s’havia acabat?

La realitat del nostre present ens obliga a mirar cap al passat per entendre el que ens està succeint. I el debat actual pivota sobre l’enfrontament de dos models, a priori antagònics, que busquen una simbiosi amigable, i que troben la seva hipèrbole en dues novel·les distòpiques escrites precisament al segle XX.

D’una banda, tenim el model que tan bé va descriure l’escriptor Aldous Huxley a la distopia ‘Un món feliç’ (1932), en què descriu un món on les persones són controlades per mitjà de l’entreteniment, les drogues i unes relacions afectives deformades. De l’altra, el model que va descriure George Orwell a la també distòpica novel·la ‘1984’ (1949), on planteja un món dirigit per una elit que, per mitjà del llenguatge i de la manipulació de la ment, ens vigila i castiga amb violència.

Serà la quarta revolució industrial, amb tota aquesta hiperconnectivitat, la que possibilitarà la coexistència d’‘Un món feliç’ i de ‘1984’ en una mateixa matriu? Són Rússia i la Xina la concreció d’aquesta simbiosi? Què passarà amb Occident, que s’encamina més aviat cap a un ‘Don’t look up!’ (No miris amunt!), com a la pel·lícula que porta el mateix nom?

Arribem al final d’aquesta radiografia econòmica, on hem analitzat les crisis dels darrers segles a partir de moments concrets. I, a mesura que ens hem apropat al present, hem abandonat l’anàlisi històrica amb què les ciències socials interpreten l’esdevenir de les generacions per convertir-nos en opinadors de l’actualitat. Com més a prop som del que ens passa, més perdem la perspectiva necessària per comprendre amb mirada crítica el que succeeix. Encara no som capaços de percebre la multidimensionalitat del present històric, perquè ens manca el pòsit temporal.

Molts dels esdeveniments actuals encara estan en marxa i molts altres ni tan sols han començat. Quin futur ens espera? No ho sabem. Sí que sabem què va succeir en el passat, sí que sabem que hi ha preguntes que la història ens ajuda a respondre. I, sobretot, sí que sabem que serà de vital importància preparar-se, construir una cultura financera sòlida, en comunitat i amb llibertat, per no tornar a caure en l’abisme, pel que vindrà.

11Onze és la fintech comunitària de Catalunya. Obre un compte descarregant la super app El Canut per Android o iOS. Uneix-te a la revolució!

Catalonia is a country with a strong advertising tradition. Barcelona has been the birthplace of internationally renowned advertising agencies, which have been recognised for their creativity. Catalan advertising began more than 150 years ago. At 11Onze we take a look back at the best moments in our history.

The first advertising company in Spain was founded in Catalonia by Rafael Roldós (1846-1918). His family was linked to the world of printing and he began his professional career as an advertising broker for the ‘Diari de Barcelona’ and soon founded Roldós y Compañía in 1872. The exhibition ‘Publicitat a Catalunya 1857-1957. Roldós i els pioners’, which was shown at the Palau Robert, brings together all this legacy.

Today, Roldós S.A. is one of the oldest advertising companies in the world and for more than 100 years it was the example to be followed by the rest of the Catalan advertising agencies. The experience of Roldós was joined by other advertising agencies, such as those of Pere Prat Gaballí, Rafael Bori, Joan Aubeyzon, José Gardó and Malcolm Thomson, who helped to consolidate a profession that mediates between advertisers and the media. At first, of course, advertisements had almost no illustrations and the texts were straightforward. “Hair wash”, “Bargain, really”, “Public notice”, “Great range” were the common slogans to catch the readers’ attention.

The rise of poster art

However, illustrations were gradually gaining ground. Catalonia was also the first place in Spain where the modern poster appeared. Industrialisation and the bourgeoisie were the main driving forces behind Modernisme, a highly charged and precious style, which also incorporated advertising, always in the latest fashion. Especially as a result of the Universal Exhibition of 1888, poster design spread throughout the country, where competitions were even organised. The book that best captures this history is undoubtedly the work directed by Carolina Serra, ‘Història de la publicitat de Catalunya’ (History of Advertising in Catalonia), which highlights the importance of this sector.

Thus, the first modernist poster is by Alexandre de Riquer for a photography brand in 1895. Others by Llorenç Brunet, Modest de Casademunt, Ramon Casas, Joan Llaverías and Francisco de Cidón will soon follow. Possibly the most recognised poster of the period is ‘4 gats. Pere Romeu’ by Casas, in which we see Romeu at the bar of the famous Barcelona restaurant Els Quatre Gats looking directly at the reader. But there are others, such as those for Anís del Mono or Codorniu.

War and repression: the emergence of new formats

With the spread of radio at the end of the 1920s, new advertising formats appeared that changed the whole face of advertising. Advertising was incorporated into the world of education and professionals began to organise themselves into associations. Poster design, moreover, took on a rationalist aesthetic and, especially during the Civil War, political messages and proclamations triumphed. The work of the Propaganda Commissariat of the Republican Generalitat to fight fascism, headed by Jaume Miravitlles, was particularly noteworthy at this time. From this period are the well-known poster-photographs by Pere Català i Pic and the transmedia campaign “El més petit de tots”.

After the Civil War, international isolation and repression led to the complete disappearance of Catalan in advertising. And it was not until the early 1950s that Catalan society once again showed an interest in consumerism. Advertisements such as Potax and Cerebrino Mandri date from this period. But 1956 was the year that marked a before and after, because it was when Televisión Española began its first broadcasts and new advertising agencies appeared that changed advertising formats forever.

The Olympic Games and the rise of the audiovisual industry

It was during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s that advertising production, art and film were perfected. New ideas were explored, created, innovated and, finally, sold. It must be understood that, at that time, advertising teams had not studied any university degree: they built the profession as they practised it. This is how multidisciplinary teams were formed, with filmmakers, graphic designers, photographers, art directors, producers and commercials.

From the simple messages of the 1960s, such as “OMO lava más blanco”, to filming would take only a few decades. With the advertising boom in the United States and the United Kingdom, the psychedelic photographs and montages of Leopoldo Pomés triumphed. Possibly the most famous was for Terry cognac with the slogan “Terry me va”. Other notable names include Jaime de la Peña and Pepe Fons of Group Films. Peña won the Golden Lion at the Cannes International Advertising Film Festival for the 1979 advert “I Feel Lois”. The Moro brothers, who spread the use of the jingle, also made a name for themselves at that time. Theirs are the “Está como nunca” from Fundador (1960) or the Gallina Blanca advert from the same year, where a hen does a striptease for the camera.

But it was from the 1980s onwards that everything took on a new dimension, culminating in a new image for Catalonia and Barcelona with the 1992 Olympic Games and the production of the Olympic film by the production companies Ovideo, Group Films and Lolafilms. At that time, the underground art of fanzines and cultural magazines had a major influence through illustrators such as Mariscal and Nazario. Group Films was joined by other agencies such as MMLB, RCP and Bassat & Asociados, and Barcelona became the advertising factory for Spain. Nenuco, Cruz Roja, Byly, Trex… By the 1990s, special effects and digital animation were incorporated, and continue to this day.

Advertising is part of our collective memory. That’s why we still remember the song of the language campaign “Parla sense vergonya”, the song “Envàs, on vas?” or the sense of peace of the Audi advert with the slogan “¿Te gusta conducir?”. We have even organised neighbourhood raids to get this year’s La Mercè poster or that of illustrator Paula Bonet. And every summer we eagerly await Estrella Damm’s “Mediterràniament” advert; and every Christmas, the La Grossa and Campofrío ads. Advertising, whether we like it or not, explains us and makes us.

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the super app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

The French Revolution, as well as bringing the concepts of liberty, equality and fraternity, also brought the beginning of the homogenisation of metric systems of weights and measures on a global scale. Until then, each territory had its own systems and each, in its own way, had tried to unify them. In 11Onze we take a look at this evolution.

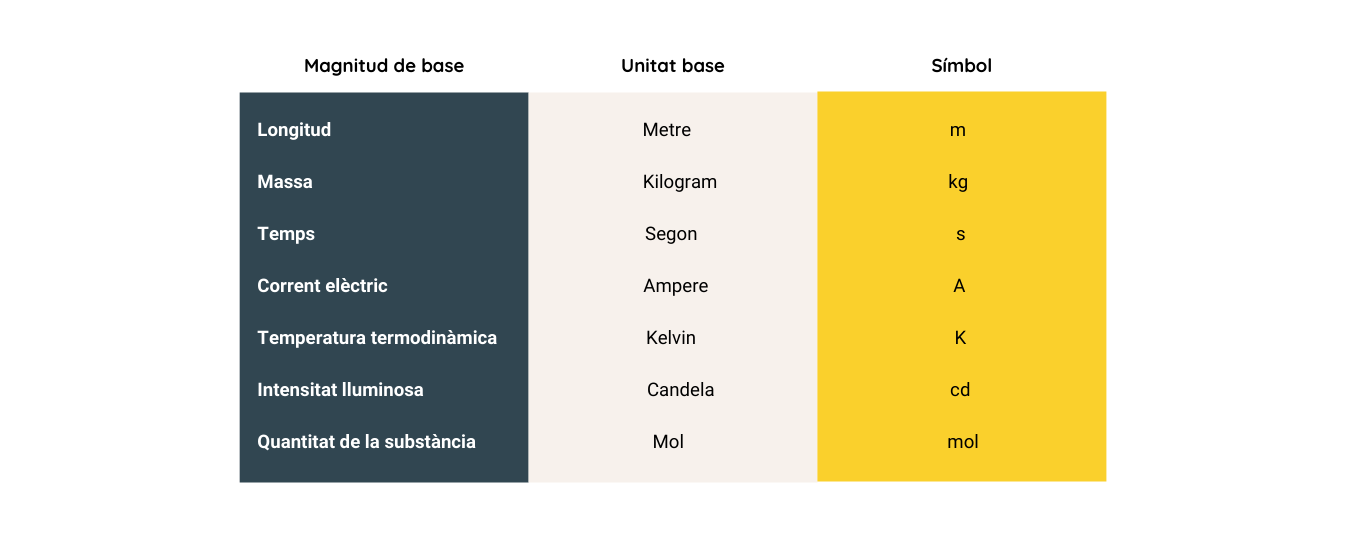

In 1791, France was the first state to adopt the decimal metric system based on the metre and the gram. From then on, the use of the gram and the metre spread throughout the world. But its acceptance as a standard metric system was not approved until 1960, when the International System of Units (SI) was internationally recognised.

It should be borne in mind that the need to measure things has been a human constant since time immemorial. For as long as mankind has had to trade goods, it has used measurement systems, which have been recorded for more than 5,000 years. Over the years, people have used measurements adapted to their circumstances. For this reason, different unique systems of weights and measures have been proposed.

The Metre Convention

Agreeing on a system of measurements has been hard work. Its acceptance by some territories is not yet 150 years old. On 20 May 1875, the Metre Convention was held in Paris, where 17 countries signed an international treaty that aimed to create a world authority in the field of metrology, the science that studies systems of weights and measures.

This treaty created three bodies that are still in force today: the General Conference of Weights and Measures (CGPM), the International Committee of Weights and Measures (ICWM) and the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM). The mission of these bodies was and is to determine a standardised measurement system. At the 11th General Conference on Weights and Measures in 1960, the well-known SI was adopted, which determined six base units. At the 14th General Conference, the seventh base quantity, the mole, was adopted.

The BIPM, in its 2018 revision of the SI, modified the definitions of four of the basic units: the kilogram, the ampere, the kelvin and the mole. The new definitions are based on the fixed numerical value of Planck’s constant (h), the elementary charge (e), Boltzmann’s constant (k) and Avogadro’s constant (NA), respectively. This fact indicates that the values are constantly being revised and that this system is redefined and refined in order to facilitate industrial production, scientific research and commercial exchange.

The metre, Barcelona and the Balearic Islands

Of all the measurements, the metre is one of the two units that was standardised from the very beginning. And Barcelona, as so often in history, played a key role. In 1799, when it was first defined, the metre was equivalent to one ten-millionth of a quadrant of the Earth’s meridian. This measurement was determined after the fraction of the Paris meridian was measured between Dunkirk and Barcelona in 1718. Later, between 1792 and 1798, geodetic triangulations were extended to the Balearic Islands. Francesc Aragó from Roussillon played an important role in the work of the second part of the survey.

Thus, in 1889 the definition of the metre was the length of the international platinum-iridium prototype, which was replaced in 1960 by the definition based on the wavelength of the radiation corresponding to a particular transition in krypton 86. This change was adopted to improve the precision with which the metre could be defined, which was achieved by using an interferometer with a travelling microscope to measure the optical path difference as the fringes were counted. But in 1983 the definition was changed again, and since then the metre has been defined as the distance that light travels in a vacuum in a given time interval.

Different systems lead to miscalculations

There are many reasons for the complexity of defining individual measurements, but the main one is undoubtedly miscalculation. History is full of misunderstandings, disputes and disasters due to the lack of a standardised system of weights and measures. Contemporary history does not escape from this, despite the fact that almost all countries have accepted the SI —except for the United States, Liberia and Burma — and has episodes that continue to vindicate the need to use a single system, especially in a world as globalised as the one we live in.

One of the most notorious cases is that of the Mars Orbiter, the first meteorological satellite that NASA sent to Mars, but which was never able to complete its work because in 1999, on reaching Mars orbit, it was lost. The exact causes are not known. However, it is known that there was a miscalculation. NASA used the imperial or Anglo-Saxon system, which uses measurements such as inches, miles and gallons, while one of the contractors used the decimal metric system, which uses measurements such as metres, kilograms and litres. One of the investigations carried out to clarify the case determined that the cause of the loss of the satellite was an error in “the conversion of units”.

Traditional Catalan magnitudes

Beyond Barcelona’s prominence in the definition of the metre, the history of metrication in Catalonia is extensive and full of nuances. The territories had created their own measurement systems, based on the legacy left to us by the Roman Empire. In fact, until not too many years ago, people still used ounces, pounds, ‘carga’, ‘petricó and ‘jornal’, among others, in their commercial jargon.

In Catalonia, the desire to unify the metrology system dates back to the 13th century. The first firm agreement, however, was reached at the Cortes de Monzón held in 1585, where the unification of the systems based on the units of measurement used in the city of Barcelona was proposed.

Unification was not easy: establishing the methodology alone took two years. The reduction of weights and measures began in the Vegueria de Barcelona in 1587 and was completed in the Vegueria de Tortosa in 1594. This laborious work has been largely preserved thanks to the minutes collected in five volumes that are kept in the Archive of the Crown of Aragon. Scholars of Catalan metrology have their point of reference there. And you, do you still use any old measurements?

The most common measures and weights in the Catalan tradition:

‘Ounce’. The Catalan weight is equal to one twelfth of a pound. Weight used in jewellery, equal to four quarters or one eighth of a mark, which is equivalent to 33.54 grams. Weight equivalent to nine drachmas. In the Modern Age, a coin of eight ‘escuts’ of gold issued on the peninsula and in the American territories that weighed one ounce, equivalent to 27 grams.

Pound. The pound was the currency of account along with wages and money in the traditional monetary system of Catalonia since Charlemagne. The Catalan unit of weight, divided into 12 ounces, was equivalent to 400 grams in the Principality, 407 grams in the Islands and 355 grams in the Valencian Country. In addition to the common pound, there were different types of special pounds, among which the following stand out: the pound of fresh fish, which was equivalent to 30 ounces; the pound of meat, which was equivalent to 36 ounces or three thirds, and the fat pound, which was equivalent to 18 ounces. It is also the unit of measurement of weight used in Anglo-Saxon countries, the value of which varies according to the system of units used. The pound as a measure of capacity for liquids was used, among other things, to measure wine and oil.

‘Petricó’. Measure of capacity for liquids, which is equivalent to a quarter of a jug.

‘Carga’. Weight equivalent to three quintals or 312 pounds. A measure of capacity of variable value according to the object measured and according to the region. The ‘carga’ of wine is equivalent to 128 ‘porrons’, i.e. 121.60 litres. The quantity of grapes put inside the carriers, which is generally equivalent to 12 ‘arroves’.

‘Cana’. Measurement typical of Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and Northern Catalonia, which is equivalent to eight palms, or six feet, or two steps, and, in Barcelona, is equal to 1.555 metres.

D’ençà que l’ésser humà va deixar el nomadisme per constituir-se en societats sedentàries, l’aparició de l’estratificació social, basada en l’acumulació de riquesa, va esdevenir un fet. Des de llavors s’han alternat períodes de bonança i de crisis. En aquesta primera part, repassem la història de les grans crisis dels segles XVII, XVIII i XIX.

En el naixement del capitalisme incipient, les crisis van sorgir sobretot per l’expansió dels mercats, els grans monopolis comercials, el consum de productes de moda i les males collites provocades per canvis mediambientals. Des de la crisi de les tulipes, fins a les companyies del mar del sud, passant per les guerres napoleòniques, els problemes del deute, de la depreciació, de la inflació i la consegüent caiguda de règims polítics emergien com ho fan avui dia. Com s’ho van fer aleshores? Com aquestes crisis van fer caure l’antic règim? Les respostes que van trobar ens poden ajudar a comprendre el nostre aquí i ara.

1637: Per què les tulipes costen tant?

Amb la Unió d’Utrecht, les 17 Províncies Unides es van conjurar per treballar plegades per deslligar-se de l’ocupació de la Corona de Castella. Aquesta lluita comuna els va permetre viure una pujança econòmica i comercial que les va dur a un dels períodes més daurats de la seva història. El procés de creixement econòmic va fer eclosió a principis del segle XVII, quan ja constituïdes com a República Holandesa, van esdevenir la primera potència econòmica mundial. Era possible compaginar l’ètica protestant i l’esperit del capitalisme sorgit dels monopolis comercials de les mars del Japó?

Sí, i el pintor neerlandès Frans Hals ho va retratar. L’artista, considerat el gran retratista flamenc del segle XVII, va pintar per a la posteritat infinitat de retrats per a les classes acomodades holandeses, que tenien molt d’interès a deixar constància de la seva bona fortuna. Un clar exemple és el seu conegut quadre ‘Retrat d’una parella’, que mostra a un matrimoni agafant-se de la mà, símbol de lleialtat.

En aquest context d’exuberància econòmica, fou quan les tulipes van adquirir una rellevància incomprensible, atès que van convertir-se en l’expressió de major ostentació econòmica que es podia mostrar en públic. Perquè ens fem una idea, durant la dècada dels anys 20, només un bulb de tulipa es podia vendre fàcilment per 1.000 florins, mentre que el sou mitjà anual d’un holandès era de 150 florins. És a dir: un neerlandès mitjà havia de treballar durant quasi deu anys per adquirir un bulb de tulipa exòtic.

Aquest exotisme desmesurat va desembocar en una bogeria per la compra de tulipes a futur que duraria anys, fins a arribar a provocar una crisi financera descomunal i la fallida total del sistema econòmic holandès a partir del 6 de febrer de 1637. Aquesta bombolla de les tulipes que va petar potser ens recorda a la bombolla immobiliària del 2008 i les maleïdes hipoteques ‘subprime’.

1720: Qui té un amic, té un tresor

Si t’ofereixen l’oportunitat d’invertir en una empresa i t’asseguren que et reportarà moltíssims beneficis, segurament t’ho pensaràs. Després, et faràs la següent pregunta: aquesta empresa exactament què produeix per generar tants beneficis? A l’Anglaterra de principis del segle XVIII, molts inversors —petits, grans i molt grans— aquesta pregunta la van obviar. De fet, ni tan sols se la van plantejar.

L’afany per conquerir nous mercats per tal d’incrementar les balances comercials de les principals monarquies europees —castellana, francesa i anglesa— va provocar importants conflictes bèl·lics continentals. I, tots ells, comportaven uns elevadíssims costos econòmics per als eraris públics. Per això, es van veure obligades a cercar el control de nous territoris d’ultramar, principalment de les Amèriques; i el domini del món, en general.

L’emissió de deute era una de les fórmules emprades pels Estats per finançar les seves polítiques expansionistes. A l’Anglaterra del 1719, la Companyia dels Mars del Sud era una de les moltes empreses que compraven part del deute. A la vegada, l’empresa emetia accions per finançar-se i amb aquests diners tornava a comprar deute. Tanmateix, a diferència de la resta de competidors, la Companyia dels Mars del Sud va aconseguir un acord crucial d’exclusivitat en esdevenir l’única companyia anglesa amb potestat per comerciar directament amb les colònies sud-americanes de la Corona Castellana.

Aquest acord va provocar que els mercats financers es veiessin desbordats per una gran eufòria compradora d’accions de la companyia. Tanmateix, no hem d’oblidar que tot aquest engranatge —ple de trucs organitzats—, era mogut per l’Estat anglès per finançar-se. El fet curiós és que aquesta companyia pràcticament no va exercir mai cap activitat, però les seves accions van pujar més d’un 1.000% en menys d’un any.

Així i tot, quan l’eufòria va desaparèixer i els preus de les accions van col·lapsar, va haver-hi una crisi de liquiditat, que es va estendre per tota l’economia anglesa i va desencadenar en una crisi de dimensions bíbliques. Per davant es va emportar a milers d’inversors que ho van perdre tot, el govern va dimitir en bloc, el Parlament es va dissoldre i una comissió gestora es va fer càrrec de la gestió del país. Els representants de la Companyia dels Mars del Sud van acabar tots a la Torre de Londres. Finalment, Anglaterra va entrar en una llarga i profunda recessió econòmica que va durar dècades.

“Què passa quan comences a construir la capital dels EUA i més del 40% dels terrenys són privats? La North American Land Company va provocar la desfeta de la xarxa creditícia de l’Atlàntic, i va acabar per accelerar el col·lapse del sistema”

1797: La construcció d’una nova capital

Reunits a la ciutat de Filadèlfia, 55 representants de les antigues colònies americanes es disposaven a redactar una innovadora i revolucionària Carta Magna per a la incipient nació. Enrere quedava la guerra i el futur semblava prometedor. La nova constitució —d’arrel il·lustrada— s’inspirava en els principis de la llibertat i la igualtat. Aquella generació d’europeus que havien crescut i lluitat per implementar els principis de la raó en les seves societats, van observar el revolucionari sistema democràtic i republicà dels recentment nascuts Estats Units com el pas definitiu cap a la modernitat. A partir d’aleshores, tots els homes esdevindrien iguals per naturalesa i davant la llei.

La constitució nord-americana plantejava la creació d’un govern federal, limitat en les seves competències, però superior als Estats, equipat amb branques executiva i judicial, i un cos legislatiu bicameral: el Senat i la Cambra de Representants. I tots aquests organismes, on s’havien d’ubicar? S’havia de construir una nova capital?

Les discussions per decidir la ubicació van ser llargues i tenses, encara que al final es va decidir que es construiria en uns extensos terrenys sobre el riu Potomac, al sud de Baltimore. L’urbanisme de la capital havia de representar l’esperit il·lustrat mitjançant grans avingudes, rotondes, extenses zones enjardinades, i tot havia de respirar un estil neoclàssic. Tanmateix, què passa quan comences a construir la capital i més del 40% dels terrenys són privats?

La North American Land Company pretenia, amb la compra dels lots de terra, vendre’ls a inversors europeus. Així i tot, aquesta venda massiva no es va materialitzar, perquè Europa estava massa entretinguda amb Napoleó, causant principal de la tensió monetària i la retirada massiva de dipòsits dels principals bancs europeus. Per això, la North American Land Company va accedir als principals mercats crediticis europeus —anglès, francès i holandès—, va provocar la desfeta de la xarxa creditícia de l’Atlàntic, i va acabar per accelerar el col·lapse del sistema i en una important aturada comercial.

1815: El món després de Viena

Una figura a cavall va emergir entre les boires matinals a la Prairie de la Rencontre, a prop de Grenoble. Dirigint-se a l’exèrcit —que el venia a detenir per haver-se escapat de l’illa d’Elba— va cridar: “Soldats! Soc el vostre emperador. No em reconeixeu?”. Al cap d’un mes i mig, entrava a París entre crits de “Visca l’Emperador!”. La història estava disposada a donar-li una nova oportunitat a en Napoleó Bonaparte.

La restauració de la monarquia francesa —i, per tant, de l’antic règim— xocava de ple amb l’esperit revolucionari que Napoleó havia estat combatent durant quasi dues dècades. Semblava que les dues concepcions sobre la gestió del poder eren irreconciliables i calia dirimir-ho en el camp de batalla. Realment, Waterloo va significar la fi del somni revolucionari d’en Bonaparte?

Els vencedors de Waterloo —Àustria, Gran Bretanya, Rússia, Prússia i França— es van citar a Viena per restaurar l’antic ordre prerevolucionari. Convençuts de redreçar la situació, aviat es van adonar que les guerres napoleòniques havien produït uns canvis radicals i profunds a Europa, així com a altres parts del món. Tots els esforços per revertir les polítiques napoleòniques van ser infructuosos.

Durant quasi 20 anys, la subjugació dels països europeus sota l’Imperi Francès va permetre introduir moltes de les característiques liberals de la Revolució Francesa: la democràcia, les lleis, el procés judicial de les Corts, l’abolició de la servitud, la reducció del poder de l’Església catòlica i la demanda d’un límit als poders de la monarquia. Un dels llegats més importants de l’expansió napoleònica a Europa va ser la instauració del dret civil i les seves institucions.

“Convençuts de redreçar la situació, els vencedors de Waterloo aviat es van adonar que les guerres napoleòniques havien produït uns canvis radicals i profunds a Europa i el món. Tots els esforços per revertir-los van ser infructuosos”

1845: El genocidi gastronòmic de la patata

A partir del segle XII, Irlanda va caure sota el domini d’Anglaterra, que va traslladar a l’illa població no autòctona perquè s’establissin com a colons. Al segle XIV, es van imposar les anomenades Normes de Kilkenny, que prohibien els matrimonis mixtos, així com l’ús del gaèlic i els costums del país. Oliver Cromwell, al segle XVII, va ordenar la confiscació de terres i altres béns dels catòlics irlandesos, que podien passar a mans dels colons protestants anglesos, els únics que podien obtenir beneficis de les terres.

Abans d’aquesta confiscació, l’alimentació tradicional irlandesa es basava en cereals, carn, lactis, verdura i fruites. Després de la confiscació, grans quantitats de productes —cereals, bestiar, lactis, aus— van començar a sortir diàriament dels ports irlandesos cap a Anglaterra. Per això, els irlandesos van ser forçats a mantenir una dieta exclusivament a base de patates i llet.

I de cop i volta, l’any 1845, a les plantacions de patates va aparèixer una terrible plaga provocada pel fong ‘Phytophthora infestans’, que es va estendre ràpidament i va afectar de manera fatídica tots els cultius de patates. La plaga va desencadenar un terrible episodi de fam per tota la pagesia irlandesa, i va causar la mort de més d’un milió de persones. Mentrestant, el Parlament anglès no va prendre cap mesura per ajudar a la pagesia irlandesa: únicament va enviar a Irlanda uns 200.000 soldats per mantenir la situació comercial sota control i evitar l’aixecament de la població. D’aquesta manera, s’assegurava que desenes de milions de caps de bestiar, tones de farina, gra, aus i productes lactis sortissin del país.

Davant d’aquesta situació tan dramàtica —agreujada per uns rigorosos hiverns—, entre el 1845 i el 1849, més d’un milió i mig d’irlandesos van decidir deixar de passar gana a les estepes verdes i emigrar al nou món.

1866: Rendibilitats fictícies

Certs estudis tècnics demostraven que a Ogassa —població situada sota el Taga— hi havia abundància de carbó, fet que possibilitaria l’explotació de la zona a gran escala. Aquesta extracció plantejava la necessitat de construir una xarxa moderna per transportar el material a un baix cost fins a Barcelona per fer funcionar les modernes màquines de vapor de la incipient indústria tèxtil. Per aquest motiu, es van destinar gran quantitat de recursos econòmics —públics i privats— a la construcció de la xarxa ferroviària catalana. Amb aquesta infraestructura es pretenia aconseguir una indústria més competitiva i diversificada.

Ràpidament, la Monarquia es va pujar al carro del desenvolupament territorial per a tot l’àmbit estatal. I la història ens ha ensenyat que la construcció d’una nova gran infraestructura a escala estatal requereix molts recursos econòmics. Moltíssims. Per això, es va haver de reformar el sistema financer estatal per mitjà de dues importants lleis: la Llei de Bancs d’Emissió i la Llei de Societats de Crèdit.

Però els mecanismes financers que havien fet possible la gran expansió de la dècada van tocar fons el 1866 amb el crac de la Borsa de Barcelona. Simplificant molt, els motius van ser tres. El primer, la progressiva acumulació de pèrdues de les principals empreses creditores —com per exemple, Catalana General de Crèdit, molt implicada en la construcció i explotació ferroviària—, que van anar demostrant que seria impossible recuperar totes les inversions realitzades. Segon, la intensa participació de la societat en el negoci ferroviari, tant en forma d’accions i obligacions en cartera com en préstecs garantits, que seria afectada per una caiguda dràstica de la seva cotització. I tercer, l’increment desmesurat dels tipus d’interès, amb els efectes inevitables sobre tot el sistema financer. Tot plegat acabaria esgotant tots els recursos econòmics atresorats durant dècades.

“Els rabassaires van haver de triar: perdre la majoria dels antics drets sobre la terra o emigrar a la ciutat i esdevenir mà d’obra barata per a les modernes fàbriques tèxtils”

1879: La mort de les vinyes

La Sentència Arbitral de Guadalupe —de finals del segle XV—, va posar fi a la qüestió de la remença a Catalunya. Una de les seves conseqüències va ser sobre la propietat de la terra, que es va anar disgregant. Les grans propietats es van anar parcel·lant en règim d’emfiteusi, semblant a un arrendament, per mitjà d’un contracte de rabassa morta. Aquest instrument jurídic tenia com a objectiu la cessió al pagès d’unes terres ermes, és a dir, no treballades, perquè aquest hi plantés ceps i treballés la vinya mentre visquessin els ceps que havia plantat. D’aquesta manera, el pagès es convertia en usufructuari de les terres que conreava, a canvi de pagar un cens anual al propietari.

Al llarg dels segles XVIII i XIX, les principals comarques catalanes productores de vi van incrementar exponencialment la seva producció agrària, a causa d’una forta demanda del mercat. Aquest fet va portar a l’increment espectacular d’explotació de noves terres, amb la consegüent necessitat d’una abundant mà d’obra i, a la llarga, un augment demogràfic. La dècada dels anys 80 del segle XIX, Catalunya va viure l’edat d’or de la vitivinicultura, mentre França estava infectada per la fil·loxera.

Aquest insecte americà atacava les arrels de la vinya i les matava lentament, la qual cosa explica la seva lenta extensió territorial. Però la fil·loxera va saltar a Catalunya per l’Empordà l’any 1879. El 1893 va arribar al Penedès, on en vuit anys va arrasar fins a 385.000 hectàrees de vinya. I el 1899 va arribar a la Terra Alta.

Encegats pels beneficis, aquella generació només va pensar en el curt termini. Ni es va plantejar la possibilitat que la fil·loxera els afectés, ni de bon tros que els pagesos haguessin d’arrencar els ceps i, encara menys, passar un temps sense produir. I, si els ceps es morien, què passaria amb els contractes de rabassa morta? La situació es va complicar. I molt.

Primer de tot, es van substituir el 99% dels ceps europeus —‘Vitis vinifera’— pels ceps americans —‘Vitis rotundifolia’—, atès que són molt més resistents a la fil·loxera. I segon, els propietaris de les terres van considerar trencats el contractes de rabassa morta amb la mort dels ceps, tot i que els rabassaires demanaven la renovació dels contractes per l’excepcionalitat de la situació. Donat l’augment de la conflictivitat, les opcions van anar encaminades en dues direccions: que els antics rabassaires esdevinguessin parcers, la qual cosa volia dir perdre la majoria dels antics drets sobre la terra o emigrar a la ciutat, i esdevenir mà d’obra barata per a les modernes fàbriques tèxtils.

11Onze és la fintech comunitària de Catalunya. Obre un compte descarregant la super app El Canut per Android o iOS. Uneix-te a la revolució!

A 11Onze ens hem engrescat i hem recopilat alguns dels llibres que s’han escrit en català sobre l’avarícia. Com s’ha construït aquesta mala fama que diu que els catalans tenim un desig excessiu d’adquirir riqueses per guardar-les?

A través de tots aquests personatges avars, patètics, miserables i egòlatres, els escriptors catalans han retratat, no només la gasiveria de la burgesia catalana i la mesquinesa del ‘lumpen’ que malda per sobreviure, sinó la societat del seu temps en conjunt, tan patològicament malalta com tots aquells que l’habiten.

- L’escanyapobres (1884) de Narcís Oller (1846-1930) ha deixat a la literatura catalana algunes obres mestres, com ara aquesta, sovint lectura obligatòria de batxillerat la qual abandona el romanticisme i se submergeix de ple en el realisme i el naturalisme. La novel·la narra les desventures de l’Oleguer, l’avar que viu a la masia de la Coma i que, per culpa del seu caràcter esquerp, es baralla amb tots els pagesos de la contrada. Oleguer sempre mostra dues cares: de cara enfora, l’home treballador que manté la masia; però, de cara endins, l’home obsessionat amb els diners que humilia els seus subalterns. De l’autor és obligatori esmentar La febre d’or (1890-1892), perquè és la gran novel·la de la Barcelona del segle XIX, on la burgesia creix sense aturador gràcies a una especulació malsana. L’obra és un retrat d’un moment crucial de la història de Catalunya.

- Terra Baixa (1897) d’Àngel Guimerà (1845 -1924). A Catalunya, sobretot durant les primeres dècades del segle XX, hem estat molt dels drames rurals i l’obra teatral d’en Guimerà és possiblement qui millor ho exemplifica. Aquesta obra mostra de forma descarnada el conflicte entre unes imaginàries terra alta i terra baixa. A partir d’una història d’amor possessiva, el drama tracta sobre les misèries de la vida al camp, les penúries de les llars catalanes de l’època i l’estructura jeràrquica de les societats rurals.

- Drames rurals (1904) de Víctor Català (1869-1966), pseudònim de Caterina Albert, també narra els drames rurals de la Catalunya de principis de segle XX. El Club Editor recopila en tres volums els contes d’aquesta gran autora catalana, que representa amb una sensibilitat sense precedents la cara més fosca de la vida rural, i que sovint s’acarnissa amb les dones.

- La Xava (1910) de Juli Vallmitjana (1873-1937), rescatat de l’oblit no fa massa, l’autor va saber retratar els ambients més pobres de la Barcelona de principis del segle XX, com també ho va fer a l’obra De la ciutat vella (1907) les quals parlen del carrer als barris de sota de Montjuïc. Narra la lluita descarnada per sobreviure i com els senyorets de Barcelona, avars i narcisistes, feien servir la pobresa més negra per construir la seva bohèmia d’or. Les seves obres, plenes d’històries petites, narren també els grans esdeveniments col·lectius de l’època, i el combat de les classes proletàries i la burgesia.

- L’auca del senyor Esteve (1907) de Santiago Rusiñol (1861-1931), també de principis del segle XX, narra la confrontació i la reconciliació entre el senyor Esteve, un comerciant arquetípic de la petita burgesia, i el seu fill, un artista modernista que no vol heretar el negoci familiar. L’obra va resseguint la vida del protagonista, un home prudent i pràctic, que ja de petit vol dedicar-se exclusivament a la seva botiga de vetes i fils, La Puntual, i que es casa amb Tomaseta, una dona del mateix tarannà. De fons, s’hi endevina Barcelona com una ciutat en procés de modernització.

- Vida Privada (1932) de Josep Maria de Sagarra (1894-1961). Després d’anys de prosperitat de la burgesia catalana a costa de l’explotació dels més pobres, qui narra com ningú la seva decadència és aquest autor. Ho fa a través de la història familiar dels Lloberola, que veu com s’esvaeix tot el seu patrimoni en mans dels més joves de la casa. Sagarra retrata amb ironia el procés de degradació social i moral de la família i fa un retrat de l’alta i la baixa societat, a través de les reunions en salons, sales de juntes i bordells. De Sagarra també cal esmentar altres obres seves, com La rambla de les floristes (1935), El cafè de la Marina (1933) o L’hostal de la Glòria (1931), perquè fan un retrat calidoscòpic dels avars i els miserables que poblen la història de Catalunya del segle XX.

- El carrer de les Camèlies (1966) de Mercè Rodoreda (1908-1983) és qui retrata els anys de la Guerra Civil i la postguerra a la perfecció. La novel·la ressegueix la vida de Cecília, una supervivent, que comença la seva vida miserable a La Rambla. Després, viu engabiada en un pis de l’Eixample i acaba venent-se en unes barraques del Carmel. Rodoreda retrata una societat consumida per l’avarícia dels anys anteriors, un viatge cap a la foscor. Aquesta tristor grisa serà una constant en les obres de Rodoreda, com ara a Aloma (1936) o a la famosa La plaça del diamant (1962). També retrà comptes amb el passat a la novel·la Mirall trencat (1974), un retrat de la decadència burgesa a l’estil de Sagarra.

- Feliçment soc una dona (1969) de Maria Aurèlia de Capmany (1918-1991). Com ho fa Rodoreda a El carrer de les Camèlies, Capmany retrata la societat del seu temps a través del personatge de la Carola, que ha viscut intensament i ha estat víctima dels clarobscurs d’una ciutat avara que creix de manera desordenada. La protagonista enceta, al principi, un viatge a la recerca de la felicitat, però agafa el camí equivocat que li farà perdre tota la innocència. Capmany també retrata aquesta ciutat vençuda pels anys avars a Betúlia (1974).

- Benzina (1983) de Quim Monzó. L’efervescència avariciosa dels feliços anys vuitanta del segle XX la retrata Monzó a través de la història de l’Heribert. El personatge, que ha triomfat al món de l’art després d’una conquesta àrdua, viu una vida condescendent i avorrida fins que s’adona que els seus amors l’enganyen amb homes extravagants.

- El cau del conill (2011) de Cristian Segura. Ja al segle XXI, Segura retrata la plàcida existència de l’empresari Amadeu Conill: les partides de tenis al migdia, les demostracions de popularitat a la tribuna del Barça, els vermuts al Turó Park o les tardes de compres a l’Illa Diagonal. L’autor relata les tribulacions d’un prohom de la burgesia barcelonina en caiguda lliure i el relleu generacional d’una classe social en una decadència feliçment aconseguida en ple món globalitzat.

- Tsunami (2020) d’Albert Pijuan. Finalment, hi trobem els tres cosins de Pijuan, fills dels tres germans fundadors d’un grup turístic amb hotels arreu del món. Als divuit anys, gaudeixen com mai i com ningú durant la inauguració del nou hotel a Sri Lanka: festes, alcohol, submarinisme, paisatges exòtics, luxe asiàtic… Però les coses canviaran dràsticament quan una alerta de tsunami s’escampa per tots els racons de l’oceà Índic.

11Onze és la comunitat fintech de Catalunya. Obre un compte descarregant l’app El Canut per Android o iOS. Uneix-te a la revolució!

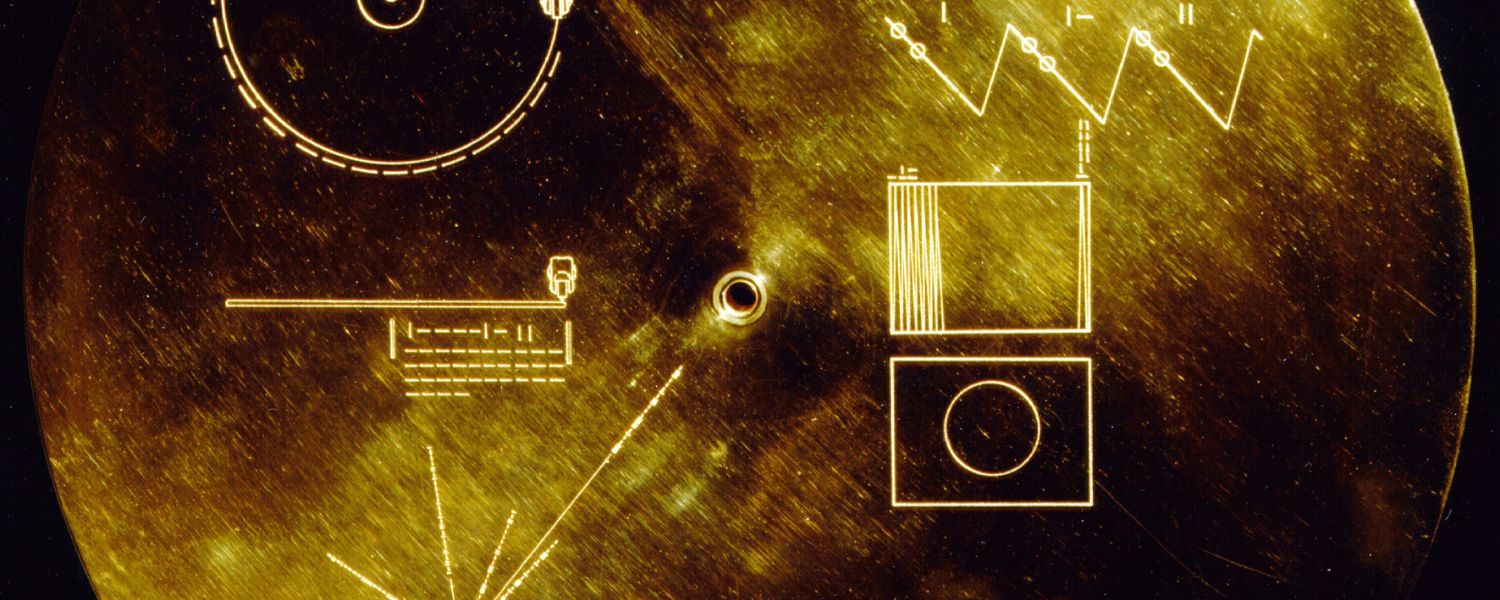

The two Voyager probes launched into space by NASA in 1977 were designed to explore the outer planets of our solar system. They were accompanied by a gramophone record made of copper and covered in gold, containing a message to show the existence of life on Earth to possible intelligent extraterrestrial beings.

In the vastness of the cosmos, two tiny time capsules traverse interstellar space with a message intended to make our existence known to any intelligent extraterrestrial life forms they may encounter along the way. A message in a cosmic bottle containing a small sample of what humanity and planet Earth are all about also symbolises our eagerness and ability to discover new frontiers.

Carl Sagan, the well-known American astrophysicist, astronomer and science communicator, led the team that created the “Golden Record” in 1972. The Voyager Programme’s Golden Record was to be an upgrade of the plates previously mounted on the Pioneer probes, with much more information about life on Earth and the essence of humanity.

The discs are thirty centimetres in diameter, made of gold-plated copper. These metals were chosen for their chemical stability and thermal properties, as they had to be strong enough to withstand the forces of the launch and subsequent thermal changes in space. A tiny amount of uranium-235 was also added to serve as a clock so that a future extraterrestrial discoverer could deduce its age.

The contents of the Golden Records

The beating of a heart, birdsongs, Bach’s Brandenburg concerto, a Balinese dancer, a human embryo… The golden records include a compendium of sounds, images, and information that provide an overview of the Earth and its inhabitants. The contents of the records range from greetings in various languages to recordings of popular music, sounds of nature, photographs of people and landscapes, and even instructions on how to play them.

Each record includes 90 minutes of music with pieces from different cultural traditions, from classical music to popular music from various countries. The intention was to capture cultural diversity and human artistic expression and show it to the rest of the universe. This idea was imprinted on the records: “To the creators of music – all worlds, all times”.

Selected nature sounds were also recorded to show some examples of what life is like on Earth, conveying the richness and complexity of our natural environment. As well as 115 photographs in analogue format, ranging from stunning landscapes to depictions of human anatomy and scientific diagrams. In addition, greetings in 55 different languages (no, there are no greetings in Catalan) were included to show the linguistic diversity of our planet.

The Voyager space probes are the most distant man-made objects from Earth and the first to reach interstellar space. Thanks to NASA’s latest efforts, they will have a lifespan until around 2026 and then continue their journey in silence. The likelihood that they will ever be found by intelligent extraterrestrial life is minuscule, but the message contained in the golden records will live on forever and ever in outer space.

If you want to discover the best option to protect your savings, enter Preciosos 11Onze. We will help you buy at the best price the safe-haven asset par excellence: physical gold.

And the next day, nothing was ever the same again. The Catalan state disappeared ‘ipso facto’ with the abolition of the Generalitat, the municipal dismemberment and the annulment of the Catalan constitutions following the loss of the War of Succession (1701 -1714). After this, the only administration that remained active in Catalonia was the army of occupation, which, by maintaining some 25,000 permanent soldiers within the Principality, consolidated the Bourbon objective by means of harsh repression that would last until the mid-18th century. But not everyone faired badly…

As a result of the victory, the elite of the Bourbon army was permanently installed in Catalonia: the Royal Castilian Guards and the Royal Walloon Guards, reinforced by other special military occupation contingents. The total number of troops deployed throughout Catalonia was 47% of the total for the rest of the Iberian Peninsula. And if we add those deployed in the rest of the territories of the Catalan Countries – Valencia, Majorca and Aragon – the figure rises to 65%. A full-blown invasion.

The drafting of the Nueva Planta Decree would turn Catalonia into just another province of a new centralised monarchy that would rule over the entire Iberian Peninsula without legal differences. Thus, the dream of a Hispanic monarchy based on the existence of different kingdoms and cultural realities on the peninsula would crumble, but it would not disappear. From then on, there would only be a single Cortes, those of Castile, which would represent the whole of the peninsular territories, but would focus on a new political construction structured around identifying Castile with the new state.

Eighteenth-century Catalonia would be a territory governed solely by the military. The supreme head of the administration of Catalonia would be the Captain General. Territorial administration – the ‘corregimientos’ – would be in the hands of the ‘corregidores’, who would always be military men. Public order – in the first instance – would always be in the hands of the army and the famous “Veciana Squads”. This institution was founded in 1719 by Pere Anton Veciana Rabassa, a deserter from the Austracist cause who in early 1713 decided to place himself at the service of the Bourbon king and create a paramilitary and police organisation that would work at the service of the Captain General -Francisco Pío de Saboya y Moura-, with the mission of continuing to repress internal Bourbon resistance.

Veciana would set up a system of criminal files – known as ‘summary files’ – which would enable the corps to systematise police information. He also created a network of informers throughout the territory and organised the first agents to infiltrate the resistance. In 1735, Veciana had to resign his post for reasons of age, and it was then that the Captain General transferred the responsibilities of the corps to his son, Pere Màrtir Veciana. From then on, the command of the corps would be inherited by the Veciana family for five generations, until 1836.

“Pere Anton Veciana y Rabassa, a deserter from the Austracist cause who at the beginning of 1713 decided to place himself at the service of the Bourbon king and create a paramilitary and police organisation that would work at the service of the Captain General -Francisco Pío de Saboya y Moura-“.

Repression and state terrorism

For eleven years, Catalonia was subjected to harsh military repression, which lasted until 1725, when, through the Treaty of Vienna between the representatives of Philip V of Castile and Charles VI of Austria, the two sides mutually recognised each other’s succession rights and put an end to the dynastic dispute.

And what happened to the supporters who fought in favour of the Archduke of Austria’s choice? During the war, as the Bourbon armies occupied the Principality, a kind of ‘military terrorism’ was applied, which consisted of persecuting the local population, regardless of the degree of connection they had had with the Austracist cause, with the aim of undermining morale. After the fall of Barcelona, the main military commanders who had not been able to flee to Austria – such as Antoni de Villarroel – were indiscriminately persecuted and sent to prisons scattered around the Iberian Peninsula. Most of them ended up dying without ever regaining their freedom, while others were sent to the galleys.

The long post-war period allowed the repression to continue against all the armed elements that were still fighting against the new legal system, such as the notorious ‘carrasclets’. But all those families whose members were in exile in Austria were also persecuted and forbidden from maintaining any correspondence. The losers of the war were to have their property seized and all their rights revoked. They would even be banned from taking part in all public tenders or applying for state aid.

The establishment of permanent contingents in Catalonia would lead to a significant increase in military demand due to the need to supply royal troops. According to the General Manuals of the Quartermaster’s Office of Catalonia – an institution created to manage the post-war period – between 1714 and 1735 a total of 271 ‘asientos’ or contracts directly related to the supply of materials to the army and navy are recorded: gunpowder, weapons, artillery trains, uniforms, food, ironwork for horses.

The ‘asientos’ were also used for the construction or supply of barracks, such as the Ciutadella, and to produce everything necessary for subsequent Bourbon military campaigns, such as those in Italy. And this supply would come about thanks to the existence of a considerable productive, commercial and financial structure that had remained unchanged despite the war, and which would be capable of solvently producing the ‘seats’ that the monarchy would need over the following decades.

“The losers of the war will have their property seized and all their rights annulled. They will even be banned from taking part in all public tenders or applying for state aid”.

Catalan collaborationism

So, the question to ask ourselves is clear: how was it possible to maintain a Catalan productive structure in the context of the war at the beginning of the 18th century? How was it possible to supply the Bourbon army during the invasion of Catalonia and the siege of Barcelona in a territory that was completely unknown to them? Well, with the help of local characters who supplied, lent or helped the Bourbon army of occupation with food, money and logistics throughout that turbulent period. They were a group of merchants who changed sides – just like Pere Anton de Veciana – in search of a more favourable personal situation and taking advantage of the circumstances to improve their social and economic position.

Names such as the Milans of Arenys, the Mates and Lapeira of Mataró or the Massiques of Vilassar and many others would be great family names that would establish their prestige throughout the 18th century for having obtained important privileges as thanks for the services rendered during the occupation of the Principality. Many of these “illustrious” figures would be placed in key institutions for the deployment and execution of the Nueva Planta Decree, because otherwise it would not have been possible.

The new regime would pass “a disinfectant cotton wool over Catalonia”, in order to subsequently build a new network of local loyalties that would consolidate it within the territory. This reason why they were placed at the head of key institutions, such as the General Treasury (Catalonia’s taxation), the General Intendancy (Catalonia’s supply and logistics), the Confiscations of Catalonia (seizure of property) and the Bureau de Change (communal bank), a minority but large sector of the Principality’s population who, for various reasons, sided with the Bourbon proposal. In this way, the monarchy combined the principle of authority, as represented by the laws deployed in the Nueva Planta Decree, with a large institutional bureaucracy and flexibility with certain local social sectors, mainly the master craftsmen and merchants, who had sufficient economic resources to boost the economy.

The self-interested attachment of these sectors of Catalan society to the new Bourbon State gave them access to new sources of income derived directly from the new policies of Bourbon absolutism. Loyalty would give them access to large public contracts, which would lead to widespread corruption at all levels of public administration.

Until the end of the 1740s, Catalonia underwent a painful period of adaptation to its new status as a defeated nation, always suspected of disaffection. From then on, economic policy decisions were no longer taken in Barcelona, but at the Bourbon Court, following criteria based on the dreams of grandeur of the new reigning monarchy, regardless of the needs of its subjects.

BASIC BIBLIOGRAPHY

Benet Oliva i Ricós: ‘Els proveïdors catalans de l’exèrcit borbònic durant el setge de Barcelona de 1713/1714’, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, 2014.

David Ferré Gispets: Els efectes del “Contractor State” borbònic a la Catalunya d’inicis del segle XVIII, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, 2019.

Josep Maria Delgado Ribas: ‘Barcelona i el model econòmic de l’absolutisme borbònic: un tret per la culata’, Barcelona Quaderns d’Història, 23 (2016), pàg. 225-242.

Josep Juan Vidal: ‘Les conseqüències de la guerra de Successió: nous imposts a la Corona d’Aragó, una penalització o un futur impuls per al creixement econòmic?’, Universitat de les Illes Balears, Palma de Mallorca, 2013.

Find out about the families that were enriched by the defeat of 1714 on 11Onze TV.

The sun set. A long, cold, and decadent night spread across Spain for almost forty years. Finally, the guns had imposed “me over you”. But the conviction and tenacity of many women made it possible to change the situation as the century progressed. We continue with the historical exercise on the history of contemporary women.

The drama increased when some 500,000 people crossed the border into France between the end of 1938 and January 1939, fleeing the horror. In fact, it had been suspected for months that this would happen. The victory of fascism in Spain became a reality in April 1939, when the hopes and illusions of a social majority that had worked to create a fairer and more egalitarian society were finally dashed. From then on, peace would be imposed under the constant threat of imprisonment for dissidents against the new order.

The regime imposed by force of arms was based on national trade unionism, but after the Second World War it was forced to move towards a different conception of power in order to ensure its survival. The world that emerged after 1945 would no longer be the same as at the end of the Spanish Civil War, since historical reality would be constructed on the basis of the confrontation between the capitalist and communist countries.

It was then that Francoism decidedly opted for National Catholicism as a social articulation. Catholic rhetoric would be more acceptable to the Western allies, the winners of the world war. And the most visible manifestation of this conception of power would be the return of hegemony to the Church, which would control all aspects of public and private life in society. The state would put the clergy on the payroll and provide the Church with a broad tax exemption and, most importantly, it would once again be given absolute freedom in the management of education.

Involution of the role of women

Franco’s dictatorship would destroy all the achievements of the Republic. The Church would legitimise the redefinition of the role of women in society. Thus, Franco’s regime would put the brakes on all the female achievements of the previous period by arguing an anti-feminist discourse, in which women would be perceived as inferior to men, both spiritually and intellectually.

Under this pretext, the new regime would relegate women to household chores, as mothers and wives. Many women were repressed by the regime, especially in the period 1939-1945. Feeding, helping or curing Republican combatants was considered a crime, for which many women were imprisoned, sent to concentration camps or even shot. Others, conditioned by fear, silenced their participation in the battlefields, making it a purely private memory.

Even so, the regime legitimised two youth organisations, the Women’s Section and the Youth Front, which were set up to indoctrinate all young people in the principles of the ‘movement’. In this way, the aim was to build a new society that was obligatorily articulated by the new values that underpinned Francoism.

A new political turn

Towards the end of the 1950s, something began to change. The failure of the autarchy and the tense international situation, with the Cold War in the background, led the regime to a forced reorganisation of forces in the power families. The Falangists, who had dominated the political scene until then and were the guarantors of fascist symbolism and rhetoric, were replaced by young technocratic politicians linked to Opus Dei.