Banking and Money Laundering: Miami Vice

The 1980s on Wall Street was a decade of big personalities, big bonuses and a culture of excess that was accompanied by a meteoric rise in drug trafficking. The pressing need to launder large amounts of drug money led to collaboration between banks and criminal organisations.

To the banks and drug cartels, Bob Musella was a wealthy American businessman dressed in Armani who owned a chain of jewellery stores and ran an investment company from Miami. What they didn’t know was that he was Robert Mazur, an undercover DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) agent who would eventually bring down drug lords and corrupt banks in one of the most successful anti-money laundering operations of all time.

“Miami is the crossroads of the international drug trade and this is where I did a lot of my business,” said Robert Mazur. With the help of two informants connected to a New York Mafia family and another based in Medellín, Colombia, Mazur mounted the most sophisticated undercover anti-money laundering operation ever conducted.

The evidence he gathered from this operation, known as C-Chase, was key for the US Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee, led at the time by Senator John Kerry, to legitimise the closure of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI), controlled by the Pakistani, Agha Hasan Abedi, which was dedicated to laundering money for the Medellín Cartel, led by Pablo Escobar.

The BCCI and the Medellín Cartel

To launder all this drug money, a series of companies were created with the help of some banking institutions, including BCCI. It was the seventh-largest private bank in the world, its reserves exceeded 20 billion dollars, and it had offices in 78 countries, including Spain.

According to US Customs documents, BCCI agents in Panama knew that the money came from drug trafficking by Colombian drug lords. They contacted Musella in December 1987 to suggest ways of laundering the money in several meetings in Miami, Paris, and London.

Law enforcement and investigative authorities nicknamed it the “International Bank of Thieves and Criminals” because of its penchant for serving customers who trafficked in guns, drugs and dirty money. Initially, the bank denied the charges, arguing it was a “malicious campaign” against the institution.

However, US and UK investigating authorities found that BCCI had been “deliberately set up to avoid centralised regulatory review, and operated extensively in secrecy jurisdictions”, adding that “its executives were sophisticated international bankers, the apparent aim of whom was to keep their affairs secret, commit large-scale fraud and avoid detection”. The entity was forced to cease all operations and shut down its business.

Fund lawsuits against banks. Get justice and returns on your savings above inflation thanks to the compensation the banks will have to pay. All the information about Litigation Funding can be found at 11Onze Recommends.

The Quantum Financial System (QFS) will introduce a new decentralised system of cross-border interbank payments based on a digital currency underpinned by physical assets such as gold.

While the world of financial services is constantly evolving, the Quantum Financial System (QFS) has the potential to revolutionise a banking sector that is often constrained by legacy systems that are overstretched by the need to adapt to the possibilities offered by new technologies.

Before delving into the role of gold within the QFS, it is important to understand that it is a new technological development that would use quantum computing and cryptography through a blockchain platform which would allow for secure and fast transactions without the need for intermediaries such as banks and financial institutions.

One of the main advantages of QFS is its ability to prevent fraud and money laundering, which are significant concerns in today’s financial system. This would be achieved through the use of advanced encryption and authentication technologies that would ensure the immutability of data, preventing manipulation and guaranteeing the integrity of transactions.

In addition, a quantum financial system would be particularly useful in applications where algorithms are fed by real-time data streams, facilitating the transfer of information and enabling near-instantaneous financial transactions, which customers could see immediately updated on their digital platforms.

The role of gold in the QFS

One of the ways in which the QFS could revolutionise the financial sector is through the creation of a digital currency backed by physical assets. This would not be a cryptocurrency but a digital currency that could be backed by physical gold, which would guarantee its value and stability. Thus, only gold-backed coins with a digital gold certificate would be able to participate in the transactions of a QFS.

The printing and pouring of large amounts of money into the economy through increasingly unsustainable fiscal deficits are damaging the credibility of the global fiat currency system and deteriorating government finances. It is therefore not surprising that economic uncertainty and loss of confidence in fiat currencies incentivise a return to fiat currencies backed by safe-haven assets such as precious metals.

In this context, gold is likely to play an increasingly important role in supporting currencies and transactions, a monetary system in which the value of currencies is underpinned by their convertibility into gold. The example of the QFS is not unique; Zimbabwe is about to introduce a gold-backed legal tender digital currency in order to help stabilise the economy in the face of the rapidly depreciating Zimbabwean dollar. A trend that some analysts see as an unmistakable sign of a paradigm shift in the international monetary system.

If you want to discover the best option to protect your savings, enter Preciosos 11Onze. We will help you buy at the best price the safe-haven asset par excellence: physical gold.

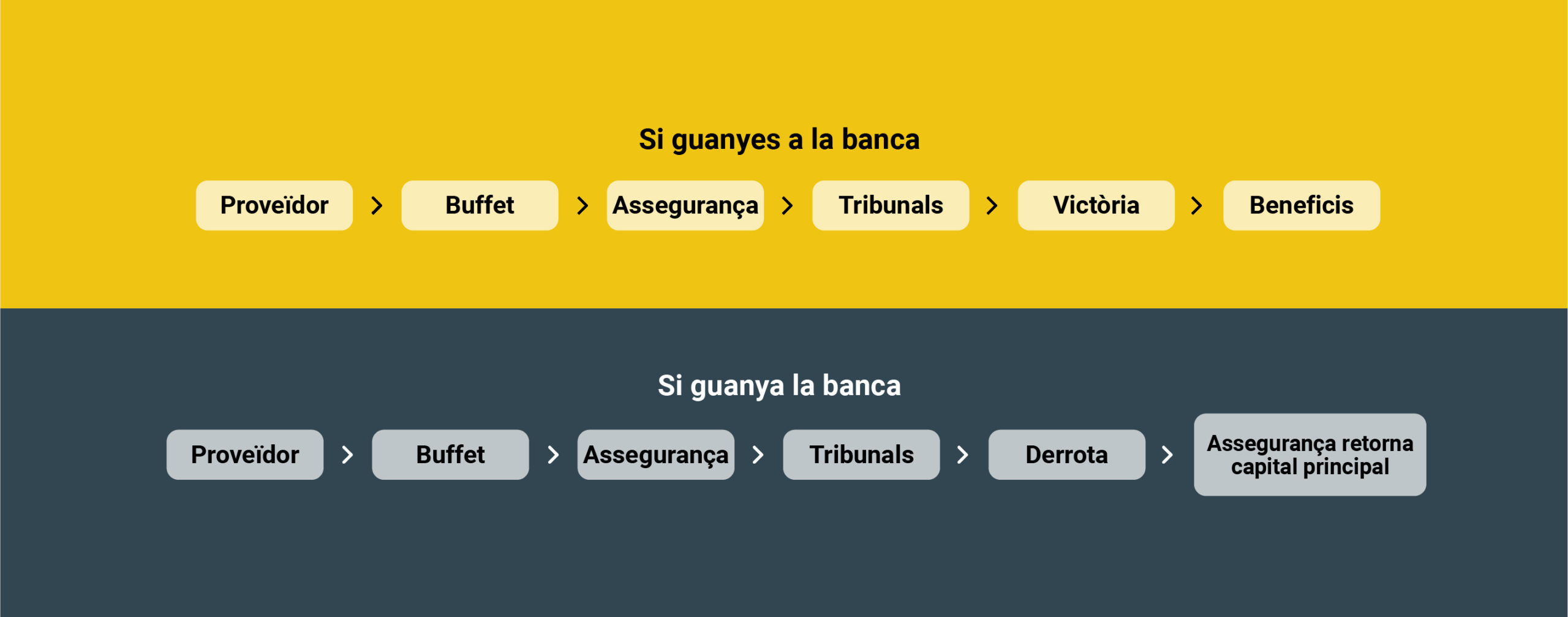

The members of our community who invested in Litigation Funding a year ago have already obtained their returns of between 9% and 11%. How was the process? Would they recommend it? Dolors Tomàs, a client of 11Onze, tells us about her experience.

It is just over a year since 11Onze Recommends launched Litigation Funding through one of our providers in the United Kingdom, offering the possibility of obtaining returns of between 9 and 11% for your money by financing the legal costs of law firms that pursue claims from citizens who were misled by banks or housing authorities.

With the capital 100% insured and a success rate on more than 90% of the litigations, the launch of this product has been a great success. But it’s one thing for us to tell you about it and another for our customers to tell you about their experience. Dolors Tomàs, a member of the 11Onze community, has invested because she trusts us and is satisfied with the results.

Social justice and high returns

For 11Onze, it is key to find feasible ways to offer socially conscious wealth creation opportunities for its community. Litigation Funding by 11Onze Recommends promises a good investment option. As James Sène, President of 11Onze explained: “Our litigation funds focus primarily on lawsuits against banks. This not only helps to deliver social justice; it also offers high returns above inflation thanks to the compensation the banks will have to pay”.

“If I found myself misled by a bank, I would not mind paying a high fee to lawyers to get justice done.”

This concept of doing social justice was one of the main reasons why Dolors decided to put her money towards Litigation Funding: “I saw that it was something that appealed to me and that was necessary. As a customer, I wouldn’t mind paying a high fee to lawyers to get a return if I was a victim of bank fraud.”

“It has worked very well. Litigation progress has been consistent through the initial formal steps by the law firm and to the point where most cases are being settled.”

How has Litigation Funding generated these profits?

Litigation Funding generates profits by funding the legal work of a law firm that focuses on lawsuits against the most delinquent municipalities and banks. As Farhaan Mir, 11Onze’s CFO, explains, “It has worked very well. The progress of litigation has been consistent through the initial formal steps by the law firm and to the point where most cases are being settled.”

“The capital is guaranteed by insurance, meaning that if the judicial process does not go as expected, and you don’t win the trial, you can get your money back”.

Dolors confirms that “everything has worked out very well” and adds that one of the reasons why she lost her fear of investing is that “the capital is guaranteed by insurance, meaning that iif the judicial process does not go as expected and you don’t win the trial, you can get your money back”. That is why 11Onze recommends this product, which is considered a unique and low-risk opportunity.

Fund lawsuits against banks. Get justice and returns on your savings above inflation thanks to the compensation the banks will have to pay. All the information about Litigation Funding can be found at 11Onze Recommends.

The public employment offer approved this year by the Catalan Government and the Spanish Government exceeds 60,000 vacancies. We offer ten tips to prepare for a civil service examination with guarantees in case you are thinking of it.

Given the instability of the labour market, you may be thinking about preparing for a civil servant competitive examination. It is undoubtedly a good time to do so, given the large public employment offer announced by both the Catalan and the Spanish governments.

If you decide to take the plunge, the first thing you need to be clear about is which option best suits your interests, your profile and your skills. Also, be aware that you will need a certain spirit of sacrifice to put in the hours of study every day, you will have to be constant and never lose motivation.

Júlia Pérez, director of the Adams training academies in Catalonia, shares ten fundamental tips for preparing for civil service examinations with guaranteed success.

- Keep the objective in mind. To stay motivated, you must never lose sight of the goal for which you are striving.

- Time management. Be clear about how much time you have to study. The more hours a day you can dedicate, the better. But, in any case, it is necessary to make a realistic plan to see how many months it will take to prepare for the exams.

- Studying the right way. We must bear in mind that studying does not mean spending hours in front of a book. It is essential to find ways to make the most of your time.

- Enjoying the study. We must try to have fun while we study so that so many hours do not turn into hell.

- Organisation. We must be very organised because we will spend many hours alone in front of books, notes and questionnaires.

- Support. Furthermore, we need to feel that our environment, both family and friends, support and help us.

- Train, train and train. This is a long-distance race, so it is a good idea to do a lot of exam practice.

- Keep negative thoughts under control. We are bound to have them, so we must try to control them. In this sense, the first point helps a lot: having a clear objective and always keeping it in our mind.

- Better in company. We must be in good company. That’s why it helps a lot to have teachers and other candidates help us not to feel so lonely.

- Taking care of yourself. You have to take good care of yourself, both body and mind, and never stop believing that you can achieve your goal. In fact, many people achieve it every year, so why shouldn’t you be one of them?

At 11Onze we have been announcing for some time that the price of gold will continue to rise and that it is a great tool for protecting our savings. That is why we launched 11Onze Preciosos in February 2022 and, since then, we have been reporting on the gold market regularly. Now the forecasts are confirmed, gold continues to break records and the mainstream media is also talking about it.

TV3 explains how many establishments that buy and sell gold are doubling or tripling their operations by accepting old gold jewellery as part of payment. In this way, they are helping to counteract the rise in gold prices.

Gold at an all-time high: resale of antique jewellery is on the rise and lower-carat pieces are being bought.

“According to analysts, the gold rush still has a way to go. Speculative investment is growing, as is the interest of individuals in buying gold on the Internet. Even some American supermarkets, such as the Costco chain, already sell gold bars, with a variety of prices to suit all budgets”.

La Vanguardia reports how the armed conflicts in Ukraine and Palestine have spurred gold purchases by the central banks of Russia, China and Turkey and have pushed the price of the golden metal to record highs.

Gold has risen 25% since the Hamas attacks and hits an all-time high

“If time is money, gold is living one of its best times. The yellow metal has been hitting record highs for several days in a row. After new consecutive monthly gains, it is close to 2,300 dollars an ounce, a figure never seen before”.

El Periódico echoes the new all-time high in the price of gold and notes that analysts attribute the price rise to the possibility of lower interest rates and the continuation of purchases by central banks.

Gold returns to all-time highs and nears $2,300 per ounce

“The precious metal continues its bullish rally of the last few days: the price of the golden metal is up 0.40% this Wednesday and is up 10.60% this year and 12.50% in the last twelve months, according to Bloomberg data.”

On Economia, the economic daily of El Nacional, notes that the boom in this precious metal on international markets has caused the Bank of Spain’s gold reserves to increase in value by 33% since October.

The gold rally makes the Bank of Spain ‘win’ 5,080 million in 6 months

“Price rises that have allowed the Spanish central bank’s gold reserves to gain 5,080 million euros since October, 33%, which, annualised, has yielded 65%.”

Ara analyses the reasons behind gold’s meteoric rise over the last five years, in which it has appreciated by 80%, and by 10% in the last month alone.

The new gold rush: strong central bank demand drives up the price of the precious metal

“The situation of economic uncertainty, with the strong inflation of recent years and the expectation of a rate cut, also boosts the price of gold. “Having gold protects you from inflation because it maintains a certain stability. Therefore, the more uncertainty, the more the price of gold rises,” Casanovas points out.

If you want to discover the best option to protect your savings, enter Preciosos 11Onze. We will help you buy at the best price the safe-haven asset par excellence: physical gold.

In recent years, the belief that our poor email management is highly harmful to the environment has spread out. The latest research relativises its impact and points to other digital habits as responsible for a significant part of global warming.

The book ‘How Bad Are Bananas? The Carbon Footprint of Everything’, published in 2010, popularised the idea that emails have a large carbon footprint. Its author estimated that each message, even if it is just to reply “thank you”, generates a minimum of 0.3 grams of CO₂ due to the energy consumption associated with our devices and, above all, with large data centres. And it should be borne in mind that between 150 billion and 300 billion emails are sent daily around the world, although most of them are ‘spam’.

Some recent research relativises this alleged environmental damage of our messages. Apart from freeing up some space on the servers that host them, there is no evidence that it substantially reduces the energy consumption of the digital infrastructure if we avoid our expendable emails and delete unnecessary ones.

We very rarely switch on a mobile phone or computer just to send an email and both storage and data transmission systems run relentlessly, even when we are not using them, so energy consumption remains fairly stable.

An updated perspective

With the new estimates, it is estimated that heating water in a kettle requires more electricity than sending and storing a thousand e-mails. And deleting that thousand messages from our inbox would have a carbon benefit of about five grams of CO₂, the minimum our computer would generate in half an hour if we kept it on to delete them. Although it may be hard to comprehend, manually deleting emails can have a greater impact on carbon emissions than storing them.

In fact, the first effective measure to limit the carbon footprint of email is to reduce as much as possible the number of electronic devices we buy to manage it and to keep them as long as possible, as their manufacture generates a significant carbon footprint.

But above all, safeguarding the environment means using energy-efficient devices and rationalising the time we keep them switched on: we should not forget that part of the electricity we use to power these devices comes from fossil fuels.

The source of excessive traffic

Obviously, avoiding unnecessary emails, writing concisely, including hyperlinks to files rather than attachments, limiting the number of recipients, regularly emptying the ‘spam’ folder and unsubscribing from newsletters that do not really interest us are best practices that will reduce Internet traffic. But if we really want to contribute with our digital habits to the good health of the planet, we should look beyond our e-mail.

Email exchanges account for only 1% of Internet traffic, which is tiny compared to video streaming services, which already account for more than 80% of what goes online. And that is an appreciable amount of tons of CO₂.

If you want to wash your clothes without polluting the planet, 11Onze Recommends Natulim.

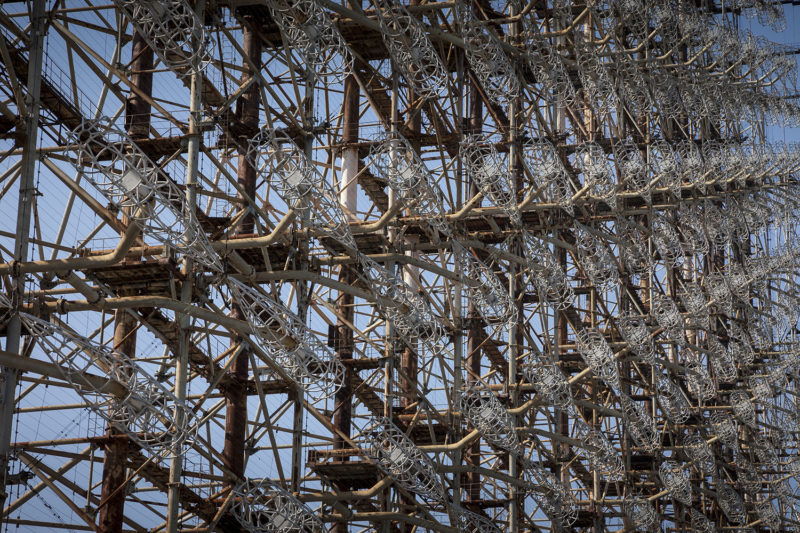

The US House of Representatives has approved another 57 billion euro aid package for Ukraine and a further 24.7 billion euros for Israel, but who will benefit from this money – the people suffering from armed conflicts or the Military Industrial Complex?

After months of stalled funding by a group of Republican lawmakers, in a rare weekend session, the US House of Representatives approved an additional package of some 89 billion euros in assistance for Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan on Saturday.

The three foreign aid items that were voted separately will provide 57 billion euros for Ukraine, 24.7 billion euros for Israel and 7.6 billion euros for security in the Indo-Pacific region, including billions for Taiwan. The package also includes a ban until March 2025 on funding to the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), which provides vital assistance in Gaza.

The bulk of this aid will go to weapons support, including new weapons systems for the Ukrainian and Israeli militaries directly from US defence contractors, as well as to resupplying US and allied weapons arsenals. Let’s not forget that the Biden administration is about to approve the sale of up to 50 F-15 fighter jets to Israel, in a deal expected to exceed $18 billion.

According to the official rhetoric of President Joe Biden’s administration, this money is an urgent and necessary sacrifice at a time when threats and wars besiege US allies. Republican opponents of the bill argued that these budget items should be tied to addressing national border security problems and the country’s growing debt burden, warning against spending more funds, many of which are channelled directly to the arms industry.

The skyrocketing profits of war

The military assistance package approved last weekend is the latest in a string of major subsidies or taxpayers’ money recycling into the arms industry since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, which has become a gold mine for the US and European MIC. This should come as no surprise, as it is often the case in every armed conflict.

According to a study by GlobalTimes, US defense contractors received almost half – $400 billion – of the $858 billion earmarked in the 2023 defence budget. Since the start of the war in Ukraine, the largest Wall Street-listed companies in the sector have accumulated share price gains of 24 billion euros.

Moreover, US weapon sales abroad rose sharply last year, reaching a record 223 billion euros, 56 per cent more than in 2022, according to State Department data.

As for the rest of NATO, the decision of the main members to increase their investment in defence due to pressure from the United States has boosted the growth projections of many multinationals in the weapons industry which, in some instances, have registered increases of up to 150% in the stock market and profits of more than 300% over the previous year, as in the case of Germany’s Rheinmetall.

Spain is experiencing the largest increase in military spending in the last 40 years. The defence budget already represents 23% more than in 2022, making it the item with the highest growth in state spending. Defence companies such as Indra, Navantia and Santa Bàrbara de Sistemas have made huge profits.

When taking into account the genocide in Gaza and the fact that the war in Ukraine has been more than lost for months, it is hard to understand how this new funding will benefit anyone, beyond the defence industry and the pockets of the politicians who are linked to it. But as BlackRock employee Serge Varlay said: politicians are easy to buy, and war is good for business.

If you want to find out how to get returns on your savings with a social justice product, 11Onze recommends Litigation Funding.

This year, university admission tests that decide the future of thousands of students will be held from 14 to 16 June. We present ‘selectivitat.io’, the definitive tool to prepare for them and give you the best chance at success.

In 2021, at the age of 22, Jaume Plana created selectivitat.io, a platform that offers all the teaching material to prepare for your GCSE, as well as for university admission tests. The initiative was born from the experience of Jaume and other people around him who had, as he describes, a feeling of abandonment when it came to studying and preparing for these exams.

In just over a year, the platform has collected all the material necessary for the subjects taken in the GCSE: notes sent by the students themselves, notes from academies and professionals, mock exams, grade calculators, courses and podcasts. All with the philosophy of free access, as Plana explains: “It’s free now and forever and ever, we believe that you don’t have to pay for educational material”.

In addition to these basic and free services, there are additional paid services for students who may need the support of a teacher to help them resolve doubts and accompany them in this process.

The grade that decides your future

This is the well-known, and dreaded for some, cut-off mark. The mark that is extracted from the ‘selectivitat’ and which will decide which degree the student can study and at which university, within the range of options that he or she has chosen. A system that Plana himself considers unfair and with a great risk of loss of talent along the way: “There are incredible people who would be perfect in entrance examinations, but they can never get there because the filtering is based on marks” when the employment sector, he remarks, “is not based on marks”.

The current education system focuses on grades from the start. Even in nursery school (from three to five years old) there are schools that initiate students into this selection system that will accompany them for the rest of their academic life. Therefore, they become accustomed to selection by grades.

However, Plana points out that they are not taught the basis of the learning process and take advantage of it. There are thousands of students who, due to a lack of organisational tools, lack of support or fear of not achieving their objectives, end up failing in this system.

Pressure closes doors

Managing pressure can be very important in terms of the results of the university entrance exams. In this sense, the mental preparation of students is relevant, as Plana explains: “Pupils who get a 14 or very good marks are very good students who know how to handle pressure very well”.

Jaume Plana also points out that we are not prepared for failure, as we are not educated to identify it as something natural and even positive. On the contrary, those who fail are singled out.

The pressure when it comes to tackling studies is subsequently transferred to the way we approach the labour market, which becomes a limiting pillar for many young people.

Therefore, in addition to academic preparation for the entrance exam, there is also mental preparation, which includes three main aspects: having the support and accompaniment to be able to face these tests; being aware that it is OK if you fail, as there will be new opportunities, and finally, making it clear that your aptitudes will be more important for your future than any grade.

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the super app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

Twenty years have just passed since the independence of East Timor, the first territory to achieve independence in the 21st century. Five others have followed: Montenegro in 2006; Kosovo, Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2008; and South Sudan in 2011.

On 20 May 2002, East Timor gained independence after a cruel Indonesian occupation and a UN-supervised transition. Montenegro followed in 2006 and Kosovo in 2008, after more than a decade of conflict in the Balkans. Also in 2008, a few countries recognised the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia in their conflict with Georgia. The last country to become independent so far in the 21st century was South Sudan in 2011.

East Timor (2002)

On 20 May 2002, this enclave in the eastern half of the island of Timor achieved full independence. It did so after a transition of more than two years under UN control. It had been preceded by centuries of Portuguese colonisation and a brutal Indonesian occupation. The new country, sandwiched between Australia and Indonesia, was at the time the poorest in Asia.

The decolonisation of East Timor has certain parallels with that of Western Sahara. Just as Spain’s withdrawal from the African colony led to Morocco’s occupation, the Portuguese withdrawal in 1975 was used by Indonesia to invade the territory and initiate a cruel repression, resulting in between 100,000 and 250,000 deaths.

The UN-sponsored referendum in 1999 was won by the independence option, which became effective in 2002. However, political and social instability continued until 2012, when the UN mission left the country for good.

East Timor, which is less than half the size of Catalonia and has a population of more than one million, has a constitution modelled on the Portuguese one. Its gross domestic product (GDP) has grown from less than $500 million in 2002 to more than $1.8 billion in 2020.

Montenegro (2006)

The territory of Montenegro was under Roman, Byzantine, Serbian and Ottoman control for two millennia, with some intervals of autonomy. In 1878 it became a principality, but after World War I it was integrated into what was to become Yugoslavia, along with Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Macedonia and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

National tensions between the different republics continued after World War II, with Yugoslavia in the communist orbit. To defuse these tensions, a new constitution was adopted in 1974 guaranteeing self-determination for each of the six Yugoslav republics.

Ethnic conflict erupted in the 1990s. Yugoslavia was dismembered, and only Montenegro remained united with Serbia, although a referendum on 21 May 2006 also established the division of the two countries. Independence was approved with more than 55% of the vote, the condition set by the European Union for accepting the new state.

Since independence, Montenegro’s GDP has grown from $2.722 billion in 2006 to $4.779 billion in 2020. The EU has granted the Balkan country candidate status.

Kosovo (2008)

Like Montenegro, Kosovo went through the domination of multiple empires and kingdoms before being integrated into Yugoslavia. In addition, ethnic clashes have marked its history since the Middle Ages.

In 1990 the region’s assembly proclaimed the Republic of Kosovo within Yugoslavia and two years later it declared independence, although Serbia did not recognise this decision. The 1998-1999 war between Serbs and Albanians ended with NATO intervention and the establishment of a UN protectorate.

Kosovo’s parliament unilaterally proclaimed independence on 17 February 2008, although it remained under international tutelage for four years. Some 100 countries and multilateral organisations have recognised the new republic, although some states, including Spain, still do not accept Kosovo’s independence.

The GDP of Kosovo, with a population of almost two million people, has risen from $5.69 billion in 2008 to $7.61 billion in 2020.

Abkhazia and South Ossetia (2008)

The situation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia is somewhat reminiscent of that of the separatist provinces of Ukraine. These two pro-Russian territories in the Caucasus proclaimed their independence from Georgia a year after the break-up of the USSR, but neither country officially recognised the two new states until 2008.

The 2008 war between Georgia and these two separatist provinces prompted Russia’s involvement, which tipped the balance in favour of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Russia and four other countries then recognised their independence, although most of the international community still considers them part of Georgia.

Abkhazia’s territory covers 8,665 km², while South Ossetia’s is less than 4,000 km². In terms of population, the population of the former is less than a quarter of a million, while the latter barely exceeds 50,000. In 2020, Abkhazia’s GDP was estimated at less than $500 million and South Ossetia’s at around $100 million. The economies of both territories are heavily dependent on Russia.

South Sudan (2011)

Located south of the Sahara Desert in Central Africa, Sudan was once dominated by the Nubians. After centuries of independence, it came under Turkish control in the early 19th century. After another period of independence in 1899, Sudan was invaded by Egypt, which was then a protectorate of the UK.

Sudan ceased to be a British colony in 1956, but ethnic and religious differences plunged it into civil war until 1972 between the Muslim-dominated north and the Christian- and animist-majority south.

Conflict broke out again in 1983 and lasted until 2005. In January of that year a peace agreement was signed guaranteeing a six-year period of autonomy for the southern region, after which a referendum on independence would be held.

In the plebiscite, held in early 2011, independence won over 98% of the vote. The southern state’s independence was officially proclaimed on 9 July of that year, leaving the country divided between Sudan and South Sudan.

With a territory almost as large as France, it has a population of around 13 million people and a GDP of just over USD 3 billion.

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the super app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

The world is constantly evolving, but information does not always move at the same pace. Wikipedia takes this need and makes it its strength: everything you need to know is just a click away. We talked to Pau Colominas, Wikipedian and one of the people in charge of social networks in the Catalan-language version of this encyclopaedia.

In a world where everything advances at an accelerated pace, keeping information up to date is practically a luxury exclusive to social networks. With a filter of objectivity (to a greater or lesser extent) and under deontological codes, the media joins in to explain the daily events that happen everywhere. But where is all this information collected? Be it facts, people, concepts, or dates, the scope of information from the internet is so complex that it becomes diffuse and even unreliable.

In a new episode of People, we talk to Pau Colominas about Wikipedia, a free encyclopaedia where many volunteers collect and disseminate all kinds of content in our language. Everything we would find in a printed encyclopaedia is there. With an important nuance: the information can be updated at any time. A milestone that can only be achieved thanks to digitalisation and the efforts of hundreds of Wikipedians who dedicate their time to disseminating knowledge in Catalan to the Catalan and international community.

Searches in Catalan and quality

Pau Colominas highlights a crucial fact: “Catalan was the second language to upload content to the platform, after English“. Since then, the creation of content in our language has been on the rise, reaching the 700,000 articles that we can currently find. The impact of our language on the platform is significant, and Colominas highlights, in particular, the quality of this content, which, he says, “is often superior to that of other languages”.

The focus of the problem, however, remains when it comes to doing searches, and he points out that “even native Catalans tend to search the internet in Spanish“. Among the reasons, Colominas identifies the configuration of computers and search engines, and the imaginary of times gone by when the presence of Catalan on the internet was low and with lower quality content.

The involvement of an entire community to disseminate knowledge

A large team of volunteers makes it possible for Wikipedia’s mission to come to fruition. Colominas explains that you don’t need to be a scholar in any of the subjects, but you do need to be willing to dedicate time. He stresses that the dissemination of knowledge does not start from the content, but from the sources: “The guarantee of Wikipedia is the guarantee of the sources you use“.

All the information that Wikipedia collects is characterised by the fact that it has been published before, and this alone reduces the scope for inventiveness. In addition, a team of Wikipedians like Pau filter and identify any content that may be offensive to individuals or groups, or that may represent a conflict of interest.

11Onze is the fintech community of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the super app El Canut on Android and Apple and join the revolution!