The improvement of the extractive system

The economic exuberance of the late 17th century will make the European monarchies believe that the wealth of the world is static and just needs to be shared out. The constant inflow of gold and silver into the economy would allow them to universalise their idea of civilisation, and they would take advantage of the wonder caused in those cultures with ancestral practices and beliefs. Of the 700 million people who will inhabit the world, almost 120 million will live in Europe, given that globalisation – begun two centuries earlier – will provide them with a food variety that will allow them to extend their life expectancy.

Oriol Garcia Farré, historian and 11Onze agent

By the end of the century, Europeans will have empirically verified the whole of the earth, which will enable them to generate cartography based on observation of reality. Gone will be the imaginary geography based on dogmatic superstitions. Thus, an infinite number of descriptions of exotic civilisations would appear in the European imaginary, which would bring about a change in tastes -more orientalised- and would give rise to a progressive critical attitude towards the beliefs that Europeans held about the world. This feeling of cultural universality will be diluted as Europeans understand that the world is also inhabited by a multitude of cultures and civilisations, which are different from the descriptions contained in the Bible.

Therefore, the adoption of critical thinking will entail the encyclopaedic codification of nature through the revolutionary scientific method, which will be based on observation, experimentation and empirical speculation. Physics – written in mathematical language – will describe the shapes and measurements of celestial bodies, using the newly created analytical geometry. And from this moment on, science will become a body of knowledge differentiated from philosophy and religion. All this will lead to a perception of reality that will cause European intellectual elites to question such basic concepts as property, justice, power and, above all, religion.

“The adoption of critical thinking will entail the encyclopaedic codification of nature through the revolutionary scientific method, which will be based on observation, experimentation and empirical speculation”.

The questioning of the divinisation of power

Clearly, the Church – both Catholic and Protestant – will have to face a multitude of dissenting voices that will doubt the divine origin of the sacred texts, since the divine authorship of the Holy Scriptures will be questioned. Religion will then become an individual and private matter between man or woman and God. And by virtue of this privatisation, Europeans will progressively free themselves from compulsory dependence on the dogmatic disciplines imposed by the Church since the 10th century.

The fact of questioning the sacred foundation that justified the existence of Christian states would crack the confessional legitimacy of the political authority represented by the monarch. With the awareness of the self – through the rational principle “cogito ergo sum” – modern philosophy was inaugurated, which led enlightened scholars to openly question the divinisation of royal power.

This innovative rational thinking will provoke a frontal clash between the supporters of absolute power – in the hands of a single person and fiercely defended by all the European monarchies – against the defenders of the natural state of the human being, who will argue that “no man can be subjected to the arbitrary will of another man, nor can he be forced to obey laws that another man would not follow as he would”. This thought will provoke a profound crisis of European consciousness, which will open the way to the invention of liberty and the claim for social equality.

Absolute power and mercantilism

The theorists of monarchical power – such as Jean Bodin and Thomas Hobbes – justified absolutism as the most perfect form of government and the only one capable of managing the vast accumulation of wealth extracted from the colonies. The high civil service – appointed by the king himself – will develop ever more efficient mechanisms to meticulously organise the state’s finances, since its profits will not only be made by introducing large quantities of gold and silver into the economic system but also by maximising exports and minimising imports with the help of strategic tariffs.

Convinced that the wealth of the world was static because it could only be taken, traded or stolen, absolutist monarchies would persecute any intrusion or private initiative that would destabilise the international trade system, such as the systematic persecution of piracy. On the other hand, the multitude of war conflicts between the different European monarchies – throughout the 17th and 18th centuries – will be seen as a necessary exchange of wealth, territories or people in which everyone will either win or lose and in this way, the economic system will be maintained, which will always have to add up to zero.

The European monarchies – overjoyed by abundance – will completely forget about the lives of their subjects. Marvelling at the situation, they were incapable of implementing social and economic improvements and soon came up against the serious problem of collective poverty within their societies. And in a context of incipient social conflict – such as that of the early 18th century – the economists of the time, Colbert, Mun, Serra or Misselden, defended the application of a low wage policy as the only way to achieve competitiveness in international trade, followed by the perverse argument that “if the population has wages above subsistence level, these will be the cause of the reduction in labour effort”.

The wealth extracted from the colonies will not only be accumulated or transformed into the productive resources that the economy requires but above all it will be used to be exhibited through the arts – architecture, painting and sculpture – the sciences and culture. And all this will lead to a paradox when the main absolutist monarchies – French, Austrian, Russian or Castilian – will be able to live in their lavish palaces, in the most exquisite and refined opulence, regardless of the scarcity of resources on which most of their subjects lived. Even so, this structural dynamic would crumble with the irruption of enlightened rationalism in European thought, which would contribute to the definitive rupture of the status quo of centuries of monarchical excesses. Enlightened despotism attributed to the monarch the mission of bringing economic progress and social welfare to all his subjects, which led to an infinite number of social conflicts. On this point, not all European monarchies tackled the problem of redistributing wealth in the same way.

“The main absolutist monarchies will be able to live in their lavish palaces, in the most exquisite and refined opulence, without caring about the scarcity of resources on which the majority of their subjects lived.”

Two solutions to the same problem

One of the answers would be provided by the Crown of Castile through its economic policies, which would still allow it to enjoy relative international predominance. However, the massive extraction of precious metals from the “New World” – which had allowed it to become obsessed with its particular idea of cultural universalisation – had led to short-sightedness and a lack of adaptability to the changing movements of the economy. Therefore, faced with the challenge of redistributing prosperity among its subjects, it will find itself trapped between a gigantic debt and a lethargic society that will depend mostly on royal decisions and the resources coming from the colonies. All this will reveal the existence of a parasitic social pyramid that will result in a single peasant – constrained by the system of censuses and privileges – being obliged to feed thirty non-producers.

Therefore, the strategy followed by the Crown of Castile – through the king’s ‘valid ones’, the famous Duke of Lerma, the Count-Duke of Olivares or Father Nithard – would be to exert strong fiscal pressure by increasing or creating new taxes on the fragile peasant economies, or on the urban classes by constantly raising prices and lowering wages. This economic programme sought to obtain the maximum resources to continue to support the idea of Empire, given that until then it had allowed them to enjoy a positive balance of trade. In contrast, the nobility and the clergy would be completely exempt from all these tax burdens, as well as allowing them to increase their income. In the end, all this led to a significant impoverishment of Castilian society, with disastrous consequences for the birth rate and the depopulation of large areas of the ‘Meseta’, which would not fully recover until the beginning of the 20th century. And to top it all off, society would be hijacked by the Court of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, which would ensure – through censorship, the creaming of “banned” books and misogynist fundamentalism – that no critical thought that shunned the official line would germinate.

On the other hand, we find the response of the northern European territories – such as the English Crown and the seventeen United Provinces – which will involve firmly introducing Enlightenment ideas into society, politics and economics. While England was to become a parliamentary monarchy through a political process that limited the power of the monarch and the separation of powers, the military union of Utrecht – made up of the seventeen United Provinces – fought energetically until the Peace of Münster against the occupation of the Crown of Castile to become the republic of the United Provinces of the North. Both territories will adopt a new approach to trade that will lead to a mutation of the economic system and will adopt a free market logic without restrictions or state protection. The generation of wealth will no longer be through blood but through the individual’s ability to accumulate capital, which will lead to the emergence of surplus value, the source of the new conflict. And in this new economic paradigm, the State will no longer have a place, given that the basic and irreducible elements that will drive this new mentality will be – both for companies and individuals – under the economic imperative of maximising profits and minimising losses.

“In contrast, the nobility and the clergy will be totally exempt from all these tax burdens, as well as allowing them to increase the collection of their rents.”

Change of the economic paradigm

The cultural universality that had prevailed until then would be replaced by new reasoning based on “if it can be shown that the economic output of all the world’s industrial production must be concentrated in Madagascar or Fiji or that the entire population of black Africa must move to the New World to work on the cotton or sugar cane plantations, there is no economic argument that can stop these initiatives”. And so capitalism will impose ever more extensive globalisation and reach ever more remote regions, which will be more profoundly transformed.

The world will be divided into productive plots according to global criteria such as “it makes no sense to produce bananas in Norway because they are much cheaper to produce in Honduras”. Therefore, when Argentinean landowners will only produce meat or Australian farmers will only be expert wool producers, they will have abandoned their own agricultural production, since it will be more profitable for them to buy grain production for their own consumption abroad. Thus, these transactions will allow them to speculate and get a better economic return on their investments.

And in this sense, both England and Holland were the only exporters of capital and financial services to the American or Asian colonies in order to destabilise the old empires – Castile and Portugal – and thus secure the raw materials for the incipient industrial revolution. The London and Antwerp stock exchanges – founded at the end of the 17th century – would become the commercial capitals of the new economy based on the expectation of speculative dynamism, which would be mainly participated in by the descendants of the Sephardic Jews expelled by the Hispanic Monarchy at the end of the 15th century.

From the beginning, both England and Holland were certain that in order to develop the new economic paradigm, a process of concentration of economic activity by means of the urbanisation of coastal areas had to be set in motion, which enabled them to promote shipbuilding and the development of manufacturing close to the ports. This allowed them to turn their coastlines into economically very dynamic and powerful areas. A similar situation occurred on the Mediterranean peninsular coast, which became one of the territories with economic growth similar to that of the territories of Northern Europe. It was then that Catalonia would acquire territorial cohesion on the basis of an urban system closely intertwined with Barcelona – as a commercial and political centre – while at the same time, the industry would develop for the nearby towns – Sants and Saint Martin de Provençales – and mercantile activity would be reoriented towards the Atlantic and the interior of the peninsula.

The political map of Europe at the end of the 15th century was shaped after the many conflictive social, political and economic events of the previous century and with a population reduced to less than 50% due to the Black Death. The new political landscape that emerged from this process showed a great variety of institutional forms of power. Alongside the two legacies of the Christian Lower Empire – the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy – the feudal monarchies that emerged from this structural impasse greatly strengthened, which legitimised them to govern differently and led them to construct a new concept of the State.

In order to sustain this new conception of the State, the European monarchies sought the basic mechanisms that would enable them to consolidate new state structures with a markedly centralising and unipersonal character. For this reason, they first fought energetically against all those powerful families – the Armagnacs, Lancastrians, Braganzas, Mèdicis and Palomas – who had the capacity to dispute their decisions. The fight would not always be through the use of violence, but plots were created to delegitimise them or a tight matrimonial policy of territorial anthropophagy would be applied to them in order to extend state property permanently, without the need for bloodshed.

The new political conception would lead to a clear cornering of the most representative organs of the citizenry – such as the Cortes, the Estados Generales or the Dietas – which would be replaced by a powerful and much more specialised council of the king. In this way, the State would multiply its presence in the territory through the creation of a powerful administrative network linked to the different activities of the new management system. Soon, the civil service would appear, with a life tenure at the end of the century, which would allow a segment of the population to become rich beyond limits simply by working in proximity to power.

Up to this point, the monarchies had been financed by their own resources through ordinary rents linked to manorial rights or the profits produced by their possessions, whether from the exploitation of forests, the stamping of coins or the slave trade. But this was no longer enough.

“The new political conception would lead to a clear cornering of the most representative organs of the citizenry – such as the Cortes, the Estados Generales or the Dietas – which would be replaced by a powerful and much more specialised council of the king.”

An economic paradigm shift

The European monarchies would assuage their ambition by imposing a three-pronged strategy: firstly, they made the supplies of the feudal system regular and plentiful, which lead to the appearance of an infinite number of extraordinary financing funds for people and goods, such as taxes on trade, the famous tax on salt, or taxes on houses, fires, and so on; Secondly, they created the need for consumption, such as new eating habits or the introduction of fashion in the need to dress; and thirdly, they freed themselves from the usual need to ask for the consent of their subjects, who – were still represented in institutional bodies – coming up against the argument that “in peacetime, this request was completely unnecessary”. But the key and fundamental element that would allow all this new machinery to work perfectly would be the creation of a standing army, aimed at domestic control – between threats and persuasion – and projecting the monarch’s power outwards.

Gold would continue to be the main problem for the European economy, since it would still be absolutely necessary for trade. Since ancient times, the East-West relationship had gone through an infinite number of ups and downs, but its balance of trade had always been in deficit – with respect to gold – as the Asian continent was poor in deposits of precious metal. The only gold that reached Europe with any regularity – since the 10th century – was Sudanese gold, but this would never satisfy the needs of the feudal economy.

“The key and fundamental element that would allow all this new machinery to work perfectly would be the creation of a standing army, aimed at domestic control – between threats and persuasion – and projecting the monarch’s power outwards.”

The study and appreciation of the Greco-Latin classics

The atmosphere of strong economic dynamism pervaded the whole of this period, forcing the European monarchies to seek new fields of action and new sources of profit to maintain the new and very costly state structures. Europe was too small a space to satisfy the ‘grandeur’ of the nascent modern states, but above all, it showed a shortage of raw materials. It was then that the real desire to get closer to the sources of African gold or oriental spices would appear.

The worldview of medieval society was conditioned by religion, imaginary legends and geographical ignorance, but this changed radically from the Quattrocento onwards with the recovery of Greek manuscripts ignored by the Church – which controlled culture – as they were considered pagan texts. With the introduction of the basic rules of correct Latin translation – promoted by Petrarch and Boccaccio – these manuscripts were correctly transcribed and took on a new meaning. The rereading of numerous classical texts – such as Euclid, Pythagoras, Ptolemy, Eratosthenes and many others – made it possible to construct new critical thinking that would lead humanist scholars to want to verify how much wisdom the ancient texts contained about the world.

This humanism would favour a definitive break with medieval tradition and would exalt the qualities proper to human nature. It would allow the discovery of the human self and give a rational meaning to its existence. This anthropocentrism would free the human being from metaphysical wonder and place him before the gates of empirical curiosity. The dissemination of this innovative thinking was made possible by the invention of the movable type printing press. But this mental change would also enable a small group of people – settled in both Sagres and Nuremberg – to begin to experiment and apply modern scientific methods based on mathematics and astronomy, which would alter the universal worldview.

“The worldview of medieval society was conditioned by religion, imaginary legends and geographical ignorance, but this changed radically from the Quattrocento onwards with the recovery of Greek manuscripts ignored by the Church – which controlled culture – as they were considered pagan texts.”

Colonial conquest and exploitation

Ambitious businessmen set out in search of maritime routes that would lead them to new territories where they could find abundant products to satisfy the growing demand of European markets. And in this context, the State would favour this expansive economy by participating – indirectly – in the commercial adventures of these daring entrepreneurs, who would boast a great deal of audacity but little Atlantic experience.

Chance and the trade winds led the first navigators to the most populated area of the American continent. The territory of the “New World” – both north and south combined – is 42.5 million km². Before the arrival of Europeans, an estimated 100 million people lived on the entire continent, as opposed to the 1 billion who live there today. Of these, some 80 million people lived in the strip between Mexico and Peru. On the other hand, in the gradual southward descent of the African continent, Europeans discovered that the Muslim world had penetrated much further than they thought. Beyond the equator, they entered a totally unknown world and discovered black Africa. With an area of 32 million km², current estimates speak of some 60 million people who could be living on the entire African continent by the end of the 15th century.

From the very beginning of the westward voyages, the first navigators were certain and aware that where they had arrived was not the East Indies, but a completely different territory. And in embellishing this fact, the state deployed all its modern legal and administrative machinery to possess it legitimately. Without entrusting themselves to anyone and by the right of conquest, the European monarchies began to claim ownership of those territories while ignoring the indigenous population. At this point, religion played a key role in justifying the destruction, annihilation and extermination of the ancestral cultures that lived harmoniously. A similar path would be followed on the African continent, although this process would begin some one hundred years later.

As the newcomers – already in the name of the Crown – moved into these new territories, they would discover that precious metals were not the only source of wealth. In less than fifty years, European markets would be supplied, in quantities unthinkable until then, with countless tropical products such as pepper, sugar, cotton and tobacco. The Atlantic coast would see the growth of a major port network stretching from Cádiz to Antwerp and would form the backbone of a new economic area. And then, the Crown would define itself as an Empire, always, with a shining sun!

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the super app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

For the first time, we are entering a rocky path where many plans are mixed up. Historical objectivity – based on documentary rigour – has been abducted by a clearly intentional narrative that has sought to justify anything that would serve to construct universality. Doubting the official narrative surrounding the “Discovery of America” – where the Hispanic matrix is based – has forced countless historians to work outside the academy, with no other resource than their wit and intelligence.

The raw material on which history is based is documentary sources. Chronicles, cartularies, wills, contracts, dispositions, novels, chants, archaeological remains or ‘Lebenswelt’, are a specific type of documentary that each historian uses to understand and explain the past, which – filtered through his or her mental framework – will end up shaping a specific perception of that reality.

It is for this reason that, during the creation of knowledge, one will engage in passionate, constructive and sterile debates. Discrediting one’s adversary with personal attacks is a symptom of dialectical incapacity. Therefore, anything outside empirical rigour evokes us into the world of fiction or coffee shop talk. But what happens when a documentary source is shown to have been altered, tampered with or burned?

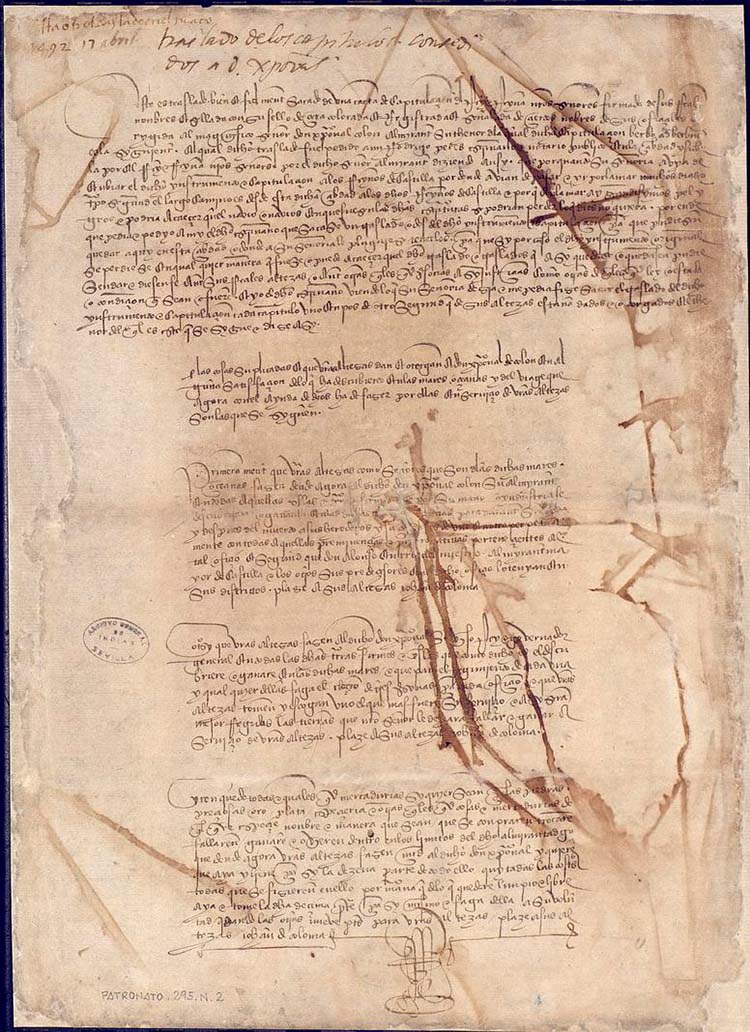

The capitulations of Santa Fe

Established in the camp of Santa Fe of Granada, the recent victors of the war of Granada, better-known as Catholic Monarchs – a title granted by Pope Alexander VI in 1496 – signed capitulations or agreements with Christopher Columbus on 30 April 1492 to carry out a major ultra-oceanic venture.

The agreements signed – known as the Capitulations of Santa Fe – would set the legal framework that would underpin the entire discovery of America, but they would also be the origin of future disputes between the Crown and the Columbus family. They will also clarify the granting of the titles of admiral, viceroy and governor-general of all the territories discovered and all the benefits derived from this enterprise.

The capitulations will acquire capital legal importance for Columbus and his descendants, and for this reason, he will never part with them during his lifetime. There is no record of the existence of this original until 1526 when it appears for the last time among the documents kept in the Columbus Archive in the Carthusian monastery of Santa María de las Cuevas (Seville). Unfortunately, this original has never reached us.

At the same time that the original of the capitulations was released to Columbus, a copy of the original was entered in the corresponding Book-Register of legal dispositions of the Royal Catalan-Aragonese Chancery in Barcelona. This entry is recorded in book 3,569, folios 135 and 136, in the ‘Diversorum sigilli secreti’ section, dated the same day of its issue, i.e. 17 April 1492. But just as the Catalan register is patented, no similar record has been found to date in any Castilian register. And it is well known that the systematic investigations carried out for centuries in the main Castilian archives -Simancas, Indias or Duque de Veragua- have so far been unsuccessful.

The legal construction of the maritime enterprise

Legislative power in the Crown of Aragon did not belong exclusively to the monarch but had to be developed together with the three estates: nobility, clergy and cities and towns. If the initiative came from the monarch, the constitution was born, while if it came from the estates of the courts, the court chapter was born.

From 1363, there is evidence of this legal practice when it came to the pairing of armies by the king with the deputies of the different estates of the Catalan-Aragonese Crown. It is for this reason that King Ferdinand signed the capitulations with Columbus, which is why one of the agreements states “perquè sia feta Armada en la Senyora del Senyor Rey, de Galées”. Therefore, neither in the legal sources of contemporary Castilian law nor in those of Indian law itself, will we find norms through which the legal concepts that appear in detail in the capitulations can be established.

The capitulations were negotiated and prepared in Barcelona by a committee formed by Joan de Coloma – representative of the Catalan Chancellery and the king’s personal secretary – and Joan Peres – Columbus’ representative – who was a prominent doctor of medicine and renowned cosmographer and owner of the castle of Sant Miquel, on the outskirts of Pals d’Empordà. And it was from the old port of this Empordà town, which no longer exists, that the ultra-oceanic expedition set sail.

When the two parties reached the agreement – on 17 April 1492 – the capitulations were immediately sent to the camp at Santa Fe de Granada – where the Catholic monarchs were staying – for official ratification (on 30 April 1492) and were subsequently handed over to Christopher Columbus. Finally, at the beginning of 1493, the Cortes Generales held in Barcelona ratified the agreement. All this justifies why these ‘Capitulations’ were kept only in the Archive of the Crown of Aragon: because that is where the documents of the magistracy concerned were recorded and archived.

“Neither in the legal sources of contemporary Castilian law nor in those of Indian law itself, will we find norms by means of which the legal concepts that appear in detail in the capitulations can be established”.

The financing of the maritime enterprise

All the surviving texts show very clearly that the money for the ultra-oceanic venture was advanced – to a large extent – by a Valencian settled in Barcelona, Lluís de Santàngel, who was the scribe of rations for the Catalan Chancellery, which often performed fiscal functions. The company was also financed by other illustrious figures such as Gabriel Sanxis – general treasurer of the Crown of Aragon -, Joan Cabrero – King Ferdinand’s waiter – and Alfons de la Cavalleria, royal adviser. It so happens that all these illustrious figures had had commercial links with the Columbus family in Barcelona for decades.

All the documents referring to the royal payments for the ultra-oceanic enterprise, count the figures in ducats, which was the Catalan currency. However, this currency was not used in Castile until 1497, when, after strong opposition from the Castilian municipalities for considering it a foreign currency, it was imposed by the monarchs.

It should be borne in mind that the structures of the two states, Aragon and Castile, always remained separate, despite the creation of bodies common to both crowns, such as the Inquisition. Therefore, each crown had its treasury, with its treasurer, its scribes and its royal archives. Consequently, if we apply the scientific method to find out who paid for the enterprise of discovery, we only have to go through the account books of both treasuries. Unfortunately, it is impossible to review the account book of the Catalan treasury, as it has disappeared. On the other hand, other contemporary Catalan sources say that thousands of ducats were being allocated to pay for ships and crews throughout that period.

But what happens when we look at the account book of the Castilian general treasury? By the way, it is public and in a modern edition! Well, there is no record of any money being spent on any maritime expedition during the nineties of the 15th century. There is no document that speaks of money referring to ships, pilots, crews or expeditions of any kind.

“Unfortunately, it is impossible to review the account book of the Catalan treasury, as it has disappeared. On the other hand, other contemporary Catalan sources speak of thousands of ducats being allocated to pay for ships and crews throughout that period.”

The triumph of the maritime enterprise

Christopher Columbus was received with full honours by the Catholic monarchs at the Royal Palace in Barcelona on 3 April 1493, after completing the first transoceanic voyage. Contemporary chronicles explain that the audience was very well received, and attracted many curious onlookers from all over the world.

Columbus had succeeded in finding the lost continent spoken of in countless ancient texts: the lands on the other side of the Atlantic “which since the sinking of Atlantis had been cut off”. And as proof of this discovery – of this “New World” – he presented the indigenous people, animals, metals and plants that they had brought back to the kings and to the highest authorities of the kingdom. Reliable proof that they came from lands hitherto unknown.

In fact, in the Capitulations of Santa Fe, it is written that the company undertook to discover territories “which are in the direction of the Indies”. Since at that time there was no geographical reference to illustrate an expedition that aimed to go to the other side of the Atlantic, the geographical reference of the Indies and China of the Great Khan was used. Both cases are extensively described in Marco Polo’s Travels at the end of the 13th century.

As the official documents of the first Columbus voyages state, the toponyms used to designate the “new places” were: Florida, l’illa Montserrat, the region of Valençuela, l’illa Margalida and la Jamaïca. It was after the expulsion of Columbus from all his American possessions and the change in the Crown’s policy in the mid-16th century that Castilian place names began to appear.

Disputes following the discovery of the maritime enterprise

When Columbus returned from his first voyage, the kings confirmed all the powers stipulated in the Capitulations de Santa Fe. But on returning from the second expedition, the monarchy realised that the lands discovered were not four lost islands, but were actually the mainland. This perception caused the monarchy to reconsider the powers granted to Columbus.

The legal problem the monarchy encountered was serious: they were aware that they had accepted and signed capitulations, which allowed the birth of a new dynasty installed in a New World and where Columbus would become viceroy for life, as well as being a hereditary title!

Aware of this problem and in the absence of the person concerned – since he was on an expedition – King Ferdinand changed the rules of the game. The viceregal reform of 1493 led to a limitation of the viceroy’s power, which would be subjugated to the power of the king and the possibility of removing him from office whenever treason against the Crown was proven. In 1500, Francisco de Bobadilla accused Columbus of betraying the Crown.

All documentation on the trial against Columbus has disappeared. From indirect sources, it is known that the Crown seized all the documentation that Columbus had to provide in his own defence. And it is also known that the reports on which the accusations were based were drawn up by Pere Bertran Margarit and Bernat Boïl.

And after all this setup, Columbus was released but deprived of all the titles signed in the capitulations. In other words, he became an inoffensive character for the powers that be. From the 16th century onwards, a long period of litigation began – first against Columbus and then against his descendants – to restore the agreements. For more than eighty years, the Columbus family would sue the monarchy, but it would prove to be a fruitless affair.

BASIC BIBLIOGRAPHY

David Bassa i Jordi Bilbeny: Totes les preguntes sobre Cristòfor Colom. Col·lecció Descoberta, Llibres de l’Índex, 2015.

Jordi Vila: Les Capitulacions colombines de 1492: un document català. 1r Simposi sobre la Descoberta Catalana d’Amèrica, Arenys de Munt, 2001.

Jordi Bilbeny: Cristòfor Colom, príncep de Catalunya, Proa, Col. Perfils, Barcelona, 2006.

Jordi Bilbeny: Inquisició i Decadència: Orígens del genocidi lingüístic i cultural a la Catalunya del segle XVI, Librooks, Barcelona, 2018.

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the super app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

And the next day, nothing was ever the same again. The Catalan state disappeared ‘ipso facto’ with the abolition of the Generalitat, the municipal dismemberment and the annulment of the Catalan constitutions following the loss of the War of Succession (1701 -1714). After this, the only administration that remained active in Catalonia was the army of occupation, which, by maintaining some 25,000 permanent soldiers within the Principality, consolidated the Bourbon objective by means of harsh repression that would last until the mid-18th century. But not everyone faired badly…

Oriol Garcia Farré, historian and agent 11Onze

As a result of the victory, the elite of the Bourbon army was permanently installed in Catalonia: the Royal Castilian Guards and the Royal Walloon Guards, reinforced by other special military occupation contingents. The total number of troops deployed throughout Catalonia was 47% of the total for the rest of the Iberian Peninsula. And if we add those deployed in the rest of the territories of the Catalan Countries – Valencia, Majorca and Aragon – the figure rises to 65%. A full-blown invasion.

The drafting of the Nueva Planta Decree would turn Catalonia into just another province of a new centralised monarchy that would rule over the entire Iberian Peninsula without legal differences. Thus, the dream of a Hispanic monarchy based on the existence of different kingdoms and cultural realities on the peninsula would crumble, but it would not disappear. From then on, there would only be a single Cortes, those of Castile, which would represent the whole of the peninsular territories, but would focus on a new political construction structured around identifying Castile with the new state.

Eighteenth-century Catalonia would be a territory governed solely by the military. The supreme head of the administration of Catalonia would be the Captain General. Territorial administration – the ‘corregimientos’ – would be in the hands of the ‘corregidores’, who would always be military men. Public order – in the first instance – would always be in the hands of the army and the famous “Veciana Squads”. This institution was founded in 1719 by Pere Anton Veciana Rabassa, a deserter from the Austracist cause who in early 1713 decided to place himself at the service of the Bourbon king and create a paramilitary and police organisation that would work at the service of the Captain General -Francisco Pío de Saboya y Moura-, with the mission of continuing to repress internal Bourbon resistance.

Veciana would set up a system of criminal files – known as ‘summary files’ – which would enable the corps to systematise police information. He also created a network of informers throughout the territory and organised the first agents to infiltrate the resistance. In 1735, Veciana had to resign his post for reasons of age, and it was then that the Captain General transferred the responsibilities of the corps to his son, Pere Màrtir Veciana. From then on, the command of the corps would be inherited by the Veciana family for five generations, until 1836.

“Pere Anton Veciana y Rabassa, a deserter from the Austracist cause who at the beginning of 1713 decided to place himself at the service of the Bourbon king and create a paramilitary and police organisation that would work at the service of the Captain General -Francisco Pío de Saboya y Moura-“.

Repression and state terrorism

For eleven years, Catalonia was subjected to harsh military repression, which lasted until 1725, when, through the Treaty of Vienna between the representatives of Philip V of Castile and Charles VI of Austria, the two sides mutually recognised each other’s succession rights and put an end to the dynastic dispute.

And what happened to the supporters who fought in favour of the Archduke of Austria’s choice? During the war, as the Bourbon armies occupied the Principality, a kind of ‘military terrorism’ was applied, which consisted of persecuting the local population, regardless of the degree of connection they had had with the Austracist cause, with the aim of undermining morale. After the fall of Barcelona, the main military commanders who had not been able to flee to Austria – such as Antoni de Villarroel – were indiscriminately persecuted and sent to prisons scattered around the Iberian Peninsula. Most of them ended up dying without ever regaining their freedom, while others were sent to the galleys.

The long post-war period allowed the repression to continue against all the armed elements that were still fighting against the new legal system, such as the notorious ‘carrasclets’. But all those families whose members were in exile in Austria were also persecuted and forbidden from maintaining any correspondence. The losers of the war were to have their property seized and all their rights revoked. They would even be banned from taking part in all public tenders or applying for state aid.

The establishment of permanent contingents in Catalonia would lead to a significant increase in military demand due to the need to supply royal troops. According to the General Manuals of the Quartermaster’s Office of Catalonia – an institution created to manage the post-war period – between 1714 and 1735 a total of 271 ‘asientos’ or contracts directly related to the supply of materials to the army and navy are recorded: gunpowder, weapons, artillery trains, uniforms, food, ironwork for horses.

The ‘asientos’ were also used for the construction or supply of barracks, such as the Ciutadella, and to produce everything necessary for subsequent Bourbon military campaigns, such as those in Italy. And this supply would come about thanks to the existence of a considerable productive, commercial and financial structure that had remained unchanged despite the war, and which would be capable of solvently producing the ‘seats’ that the monarchy would need over the following decades.

“The losers of the war will have their property seized and all their rights annulled. They will even be banned from taking part in all public tenders or applying for state aid”.

Catalan collaborationism

So, the question to ask ourselves is clear: how was it possible to maintain a Catalan productive structure in the context of the war at the beginning of the 18th century? How was it possible to supply the Bourbon army during the invasion of Catalonia and the siege of Barcelona in a territory that was completely unknown to them? Well, with the help of local characters who supplied, lent or helped the Bourbon army of occupation with food, money and logistics throughout that turbulent period. They were a group of merchants who changed sides – just like Pere Anton de Veciana – in search of a more favourable personal situation and taking advantage of the circumstances to improve their social and economic position.

Names such as the Milans of Arenys, the Mates and Lapeira of Mataró or the Massiques of Vilassar and many others would be great family names that would establish their prestige throughout the 18th century for having obtained important privileges as thanks for the services rendered during the occupation of the Principality. Many of these “illustrious” figures would be placed in key institutions for the deployment and execution of the Nueva Planta Decree, because otherwise it would not have been possible.

The new regime would pass “a disinfectant cotton wool over Catalonia”, in order to subsequently build a new network of local loyalties that would consolidate it within the territory. This reason why they were placed at the head of key institutions, such as the General Treasury (Catalonia’s taxation), the General Intendancy (Catalonia’s supply and logistics), the Confiscations of Catalonia (seizure of property) and the Bureau de Change (communal bank), a minority but large sector of the Principality’s population who, for various reasons, sided with the Bourbon proposal. In this way, the monarchy combined the principle of authority, as represented by the laws deployed in the Nueva Planta Decree, with a large institutional bureaucracy and flexibility with certain local social sectors, mainly the master craftsmen and merchants, who had sufficient economic resources to boost the economy.

The self-interested attachment of these sectors of Catalan society to the new Bourbon State gave them access to new sources of income derived directly from the new policies of Bourbon absolutism. Loyalty would give them access to large public contracts, which would lead to widespread corruption at all levels of public administration.

Until the end of the 1740s, Catalonia underwent a painful period of adaptation to its new status as a defeated nation, always suspected of disaffection. From then on, economic policy decisions were no longer taken in Barcelona, but at the Bourbon Court, following criteria based on the dreams of grandeur of the new reigning monarchy, regardless of the needs of its subjects.

BASIC BIBLIOGRAPHY

Benet Oliva i Ricós: ‘Els proveïdors catalans de l’exèrcit borbònic durant el setge de Barcelona de 1713/1714’, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, 2014.

David Ferré Gispets: Els efectes del “Contractor State” borbònic a la Catalunya d’inicis del segle XVIII, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, 2019.

Josep Maria Delgado Ribas: ‘Barcelona i el model econòmic de l’absolutisme borbònic: un tret per la culata’, Barcelona Quaderns d’Història, 23 (2016), pàg. 225-242.

Josep Juan Vidal: ‘Les conseqüències de la guerra de Successió: nous imposts a la Corona d’Aragó, una penalització o un futur impuls per al creixement econòmic?’, Universitat de les Illes Balears, Palma de Mallorca, 2013.

Find out about the families that were enriched by the defeat of 1714 on 11Onze TV.