The “Discovery of America”: the big lie

For the first time, we are entering a rocky path where many plans are mixed up. Historical objectivity – based on documentary rigour – has been abducted by a clearly intentional narrative that has sought to justify anything that would serve to construct universality. Doubting the official narrative surrounding the “Discovery of America” – where the Hispanic matrix is based – has forced countless historians to work outside the academy, with no other resource than their wit and intelligence.

The raw material on which history is based is documentary sources. Chronicles, cartularies, wills, contracts, dispositions, novels, chants, archaeological remains or ‘Lebenswelt’, are a specific type of documentary that each historian uses to understand and explain the past, which – filtered through his or her mental framework – will end up shaping a specific perception of that reality.

It is for this reason that, during the creation of knowledge, one will engage in passionate, constructive and sterile debates. Discrediting one’s adversary with personal attacks is a symptom of dialectical incapacity. Therefore, anything outside empirical rigour evokes us into the world of fiction or coffee shop talk. But what happens when a documentary source is shown to have been altered, tampered with or burned?

The capitulations of Santa Fe

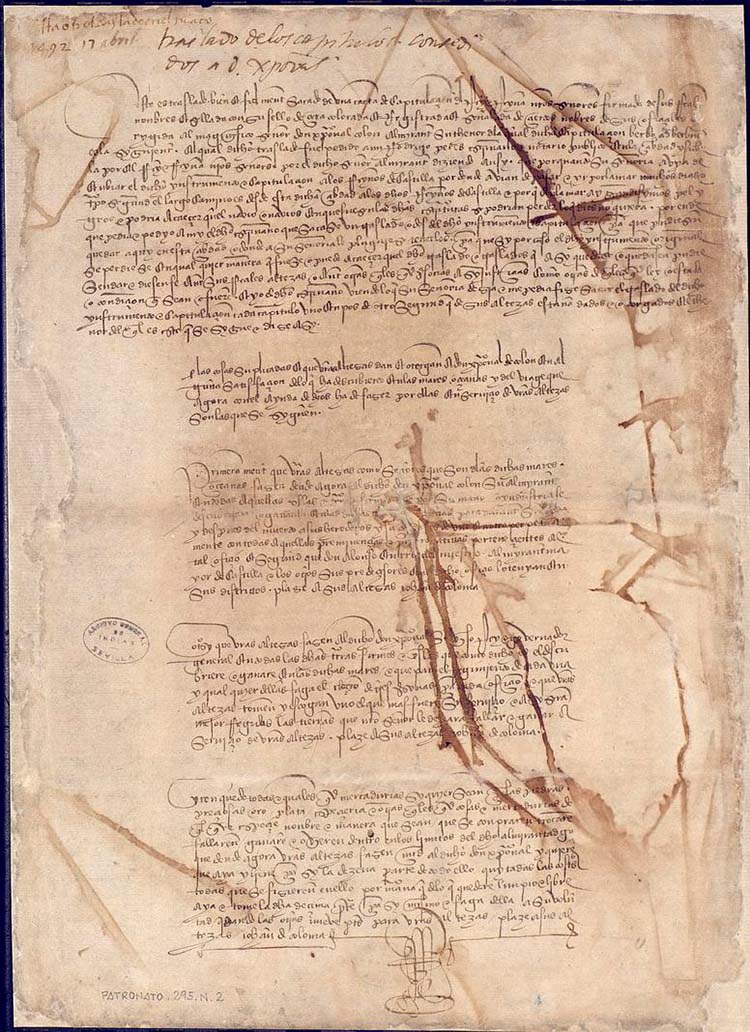

Established in the camp of Santa Fe of Granada, the recent victors of the war of Granada, better-known as Catholic Monarchs – a title granted by Pope Alexander VI in 1496 – signed capitulations or agreements with Christopher Columbus on 30 April 1492 to carry out a major ultra-oceanic venture.

The agreements signed – known as the Capitulations of Santa Fe – would set the legal framework that would underpin the entire discovery of America, but they would also be the origin of future disputes between the Crown and the Columbus family. They will also clarify the granting of the titles of admiral, viceroy and governor-general of all the territories discovered and all the benefits derived from this enterprise.

The capitulations will acquire capital legal importance for Columbus and his descendants, and for this reason, he will never part with them during his lifetime. There is no record of the existence of this original until 1526 when it appears for the last time among the documents kept in the Columbus Archive in the Carthusian monastery of Santa María de las Cuevas (Seville). Unfortunately, this original has never reached us.

At the same time that the original of the capitulations was released to Columbus, a copy of the original was entered in the corresponding Book-Register of legal dispositions of the Royal Catalan-Aragonese Chancery in Barcelona. This entry is recorded in book 3,569, folios 135 and 136, in the ‘Diversorum sigilli secreti’ section, dated the same day of its issue, i.e. 17 April 1492. But just as the Catalan register is patented, no similar record has been found to date in any Castilian register. And it is well known that the systematic investigations carried out for centuries in the main Castilian archives -Simancas, Indias or Duque de Veragua- have so far been unsuccessful.

The legal construction of the maritime enterprise

Legislative power in the Crown of Aragon did not belong exclusively to the monarch but had to be developed together with the three estates: nobility, clergy and cities and towns. If the initiative came from the monarch, the constitution was born, while if it came from the estates of the courts, the court chapter was born.

From 1363, there is evidence of this legal practice when it came to the pairing of armies by the king with the deputies of the different estates of the Catalan-Aragonese Crown. It is for this reason that King Ferdinand signed the capitulations with Columbus, which is why one of the agreements states “perquè sia feta Armada en la Senyora del Senyor Rey, de Galées”. Therefore, neither in the legal sources of contemporary Castilian law nor in those of Indian law itself, will we find norms through which the legal concepts that appear in detail in the capitulations can be established.

The capitulations were negotiated and prepared in Barcelona by a committee formed by Joan de Coloma – representative of the Catalan Chancellery and the king’s personal secretary – and Joan Peres – Columbus’ representative – who was a prominent doctor of medicine and renowned cosmographer and owner of the castle of Sant Miquel, on the outskirts of Pals d’Empordà. And it was from the old port of this Empordà town, which no longer exists, that the ultra-oceanic expedition set sail.

When the two parties reached the agreement – on 17 April 1492 – the capitulations were immediately sent to the camp at Santa Fe de Granada – where the Catholic monarchs were staying – for official ratification (on 30 April 1492) and were subsequently handed over to Christopher Columbus. Finally, at the beginning of 1493, the Cortes Generales held in Barcelona ratified the agreement. All this justifies why these ‘Capitulations’ were kept only in the Archive of the Crown of Aragon: because that is where the documents of the magistracy concerned were recorded and archived.

“Neither in the legal sources of contemporary Castilian law nor in those of Indian law itself, will we find norms by means of which the legal concepts that appear in detail in the capitulations can be established”.

The financing of the maritime enterprise

All the surviving texts show very clearly that the money for the ultra-oceanic venture was advanced – to a large extent – by a Valencian settled in Barcelona, Lluís de Santàngel, who was the scribe of rations for the Catalan Chancellery, which often performed fiscal functions. The company was also financed by other illustrious figures such as Gabriel Sanxis – general treasurer of the Crown of Aragon -, Joan Cabrero – King Ferdinand’s waiter – and Alfons de la Cavalleria, royal adviser. It so happens that all these illustrious figures had had commercial links with the Columbus family in Barcelona for decades.

All the documents referring to the royal payments for the ultra-oceanic enterprise, count the figures in ducats, which was the Catalan currency. However, this currency was not used in Castile until 1497, when, after strong opposition from the Castilian municipalities for considering it a foreign currency, it was imposed by the monarchs.

It should be borne in mind that the structures of the two states, Aragon and Castile, always remained separate, despite the creation of bodies common to both crowns, such as the Inquisition. Therefore, each crown had its treasury, with its treasurer, its scribes and its royal archives. Consequently, if we apply the scientific method to find out who paid for the enterprise of discovery, we only have to go through the account books of both treasuries. Unfortunately, it is impossible to review the account book of the Catalan treasury, as it has disappeared. On the other hand, other contemporary Catalan sources say that thousands of ducats were being allocated to pay for ships and crews throughout that period.

But what happens when we look at the account book of the Castilian general treasury? By the way, it is public and in a modern edition! Well, there is no record of any money being spent on any maritime expedition during the nineties of the 15th century. There is no document that speaks of money referring to ships, pilots, crews or expeditions of any kind.

“Unfortunately, it is impossible to review the account book of the Catalan treasury, as it has disappeared. On the other hand, other contemporary Catalan sources speak of thousands of ducats being allocated to pay for ships and crews throughout that period.”

The triumph of the maritime enterprise

Christopher Columbus was received with full honours by the Catholic monarchs at the Royal Palace in Barcelona on 3 April 1493, after completing the first transoceanic voyage. Contemporary chronicles explain that the audience was very well received, and attracted many curious onlookers from all over the world.

Columbus had succeeded in finding the lost continent spoken of in countless ancient texts: the lands on the other side of the Atlantic “which since the sinking of Atlantis had been cut off”. And as proof of this discovery – of this “New World” – he presented the indigenous people, animals, metals and plants that they had brought back to the kings and to the highest authorities of the kingdom. Reliable proof that they came from lands hitherto unknown.

In fact, in the Capitulations of Santa Fe, it is written that the company undertook to discover territories “which are in the direction of the Indies”. Since at that time there was no geographical reference to illustrate an expedition that aimed to go to the other side of the Atlantic, the geographical reference of the Indies and China of the Great Khan was used. Both cases are extensively described in Marco Polo’s Travels at the end of the 13th century.

As the official documents of the first Columbus voyages state, the toponyms used to designate the “new places” were: Florida, l’illa Montserrat, the region of Valençuela, l’illa Margalida and la Jamaïca. It was after the expulsion of Columbus from all his American possessions and the change in the Crown’s policy in the mid-16th century that Castilian place names began to appear.

Disputes following the discovery of the maritime enterprise

When Columbus returned from his first voyage, the kings confirmed all the powers stipulated in the Capitulations de Santa Fe. But on returning from the second expedition, the monarchy realised that the lands discovered were not four lost islands, but were actually the mainland. This perception caused the monarchy to reconsider the powers granted to Columbus.

The legal problem the monarchy encountered was serious: they were aware that they had accepted and signed capitulations, which allowed the birth of a new dynasty installed in a New World and where Columbus would become viceroy for life, as well as being a hereditary title!

Aware of this problem and in the absence of the person concerned – since he was on an expedition – King Ferdinand changed the rules of the game. The viceregal reform of 1493 led to a limitation of the viceroy’s power, which would be subjugated to the power of the king and the possibility of removing him from office whenever treason against the Crown was proven. In 1500, Francisco de Bobadilla accused Columbus of betraying the Crown.

All documentation on the trial against Columbus has disappeared. From indirect sources, it is known that the Crown seized all the documentation that Columbus had to provide in his own defence. And it is also known that the reports on which the accusations were based were drawn up by Pere Bertran Margarit and Bernat Boïl.

And after all this setup, Columbus was released but deprived of all the titles signed in the capitulations. In other words, he became an inoffensive character for the powers that be. From the 16th century onwards, a long period of litigation began – first against Columbus and then against his descendants – to restore the agreements. For more than eighty years, the Columbus family would sue the monarchy, but it would prove to be a fruitless affair.

BASIC BIBLIOGRAPHY

David Bassa i Jordi Bilbeny: Totes les preguntes sobre Cristòfor Colom. Col·lecció Descoberta, Llibres de l’Índex, 2015.

Jordi Vila: Les Capitulacions colombines de 1492: un document català. 1r Simposi sobre la Descoberta Catalana d’Amèrica, Arenys de Munt, 2001.

Jordi Bilbeny: Cristòfor Colom, príncep de Catalunya, Proa, Col. Perfils, Barcelona, 2006.

Jordi Bilbeny: Inquisició i Decadència: Orígens del genocidi lingüístic i cultural a la Catalunya del segle XVI, Librooks, Barcelona, 2018.

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the super app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bon article! Gràcies!

Gràcies, Joan! Seguim a La Plaça!

Sí, molt bona classe d’història, impressionant feinada i amb bibliografia i tot 👏👏👏👏

Gràcies, Jordi, pel comentari! Celebrem que t’hagi agradat l’article. Seguim a La Plaça.

👌🙌🙌Gràcies Oriol per ser atrevit, molt atrevit. L’ article és or pur.

Gràcies per les cites bibliogràfiques, en especial al Jordi Bilbeny.

Qui té tot el mèrit del món és en Jordi Bilbeny! Nosaltres hem amplificat els seus raonaments basats en la lògica i l’empirisme documental. Res més! Gràcies pel comentari. Seguim a La Plaça!