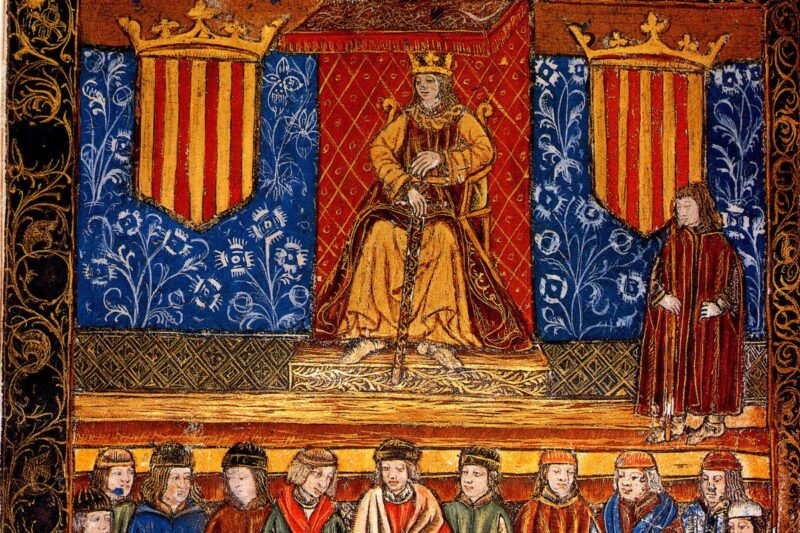

Columbus family on trial

Until the mid-20th century, the official version of the transoceanic expedition that led to the discovery of the “New World” was somewhere between myth and romantic argument. But nothing of what had been recounted until then has turned out to be entirely true, not even the places of departure and return. For decades, a small group of historians – rejected by the academy and ignored by the media – have persisted in their work of dismantling a web of falsehoods surrounding the true facts.

If we shy away from fantasy and focus on making a true analysis of historical reality, which is based on the objective and scientific study of documentary sources – be they direct or indirect, primary or secondary – we will quickly realise that the usurpation of the historical identity of the transoceanic expedition carried out against the Catalan admiral Christopher Columbus is a fact.

Without any economic or institutional baggage to condition their research, a small group of historians have been able to find the true version of the discovery of America and the real identity of its protagonists that was silenced by Castilian censorship. Comparative studies of popular manuals, general histories and planispheres, whether in Castilian, Portuguese or French editions, have revealed how the Crown of Castile – through pervasive censorship supported by specific laws – came to control most of the narrative about the American expedition. Fortunately, curiosity has unmasked the manipulation and revealed the crudeness with which the Crown of Castile worked to manipulate the facts in order to confuse public opinion about the true authorship of the discovery.

Therefore, we should not be surprised that the Castilian epic appears at the beginning of the 16th century, just when Columbus was stripped of all the titles signed in the “Capitulaciones de Santa Fe” which, let us remember, was the legal framework that supported the whole discovery of America. With that trial, the Crown succeeded in making the Columbus family a harmless family in the eyes of the authorities. Indeed, a long period of litigation began thereafter – first against Christopher Columbus and then against his descendants – to nullify the agreements. For more than eighty years, the Columbus family would sue the monarchy, but it would prove to be a fruitless affair.

Manipulated documentation

The task set in motion – first by the Crown of Castile and later by Spain – has promoted over the centuries a series of official and singular versions, with an infinite amount of mixed-up data, unlikely places, real characters mixed with fictitious ones, changes of identity or disparity in the natural origins of the main characters. This has made it possible to configure a novelistic story, mutable to the tastes of the audience and handy for covering the needs of Spanish politics at any given moment. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that the epic has been based on a premeditated false narrative. But this confusion has begun to dissipate with the emergence of prominent scholars from outside Spanish circles, who have managed to reverse the tendency to repeat the official narrative as a set mantra.

An example of this changing trend has been the research of the American historian Alícia Gould, which has made it possible to trace all the surnames of the expedition members that appear in the supposed official records of Columbus’ different voyages, and has led to the following conclusion: nothing is true, everything is smoke and mirrors! Her research has gone far beyond the texts that list the names of the crew members. The investigation found that most of the crew members’ surnames do not have any documentary continuation that certifies that the sailor or individual – who appears in the lists – had a real and effective existence. But it is also very surprising that in these notorious lists, no Catalan surname appears among the crew. So, if we think that all these surnames have been manipulated, and we look for their equivalents in Catalan – Garay for Garau or Fernández for Ferrandis or Cases for Casaus – it turns out that they all fit in with very well-documented surnames, not only as real Catalan characters in flesh and blood but also as sailors, cosmographers or military men.

In conclusion, the Columbus chronicles that have come down to us denote a clear manipulation, given that they are full of anachronisms and significant temporal inconsistencies, something that seems inexplicable when the main source was supposedly a bibliophile, cultured and with a great memory, like Columbus’ son. Textual examination has shown that all these supposed originals have been retouched. For this reason, to trust the sources without applying any kind of documentary criticism, or suspecting the political intentions of the book’s arrangers, leads us, rather than to value rigour and historiographical academicism, to rely on faith.

The task set in motion – first by the Crown of Castile and later by Spain – has made it possible to configure a novelistic story, mutable to the tastes of the audience and handy for covering the needs of Spanish politics at any given moment.

The departure point of the expedition

Today we know from outstanding research work done by historians – both the pioneering Núria Coll and Eva Sans – that the town of Pals d’Empordà had an important natural port. We know this because these studies have made it possible to document countless witnesses that speak of commercial transactions that were carried out and, therefore, we know it had become an important commercial port since the beginning of the 13th century. In addition, toponymy and landscape archaeology have made it possible to identify both the remains of buildings and geographical features documented on ancient maps. All this, combined with palaeo-hydrographic studies of the area around Pals, confirm what the documents testify to.

Bearing in mind that the surface of the planet is exposed to constant change that causes regular movements, and we understand that the seas move away from the beaches or the other way around, we will understand that the surroundings of Pals at the end of the 15th century have nothing to do with the landscape of Pals that we see today. Obviously.

Therefore, what is most surprising about the official version – as far as the departure point of Columbus’ transoceanic expedition is concerned – is the name: Palos de Moguer. This is undoubtedly the same case as Sant Esteve de les Roures, two places that do not exist, nor have they ever existed. Certainly, in the province of Huelva, there are two villages, separated by 16 km, which correspond to the place names Palos de la Frontera and Moguer. Both are located more than 40 km from the Atlantic coast. And as if this were not enough, it is even more surprising when we find out that neither of the two places has ever been surrounded by walls or had a 21.28 metre-high Catalan Gothic bell tower.

Let us keep in mind that in the 15th century, Catalonia had become an important European nautical power. In fact, it is where the most outstanding pilot schools, cosmography centres, navigation instrumentation workshops and a host of specialists in the production of nautical charts were to be found. Moreover, since the mid-13th century, the Principality had pursued a very active insular policy that consolidated more than a hundred consulates of the sea scattered throughout the Mediterranean.

By contrast, at the same time, in Castile, there were no nautical schools, no pilot schools, no cosmography centres, nor any kind of nautical infrastructure capable of carrying out a transoceanic expedition such as the one undertaken by the Catalan admiral Christopher Columbus. Many historians point out the profound contradiction of the American expedition in itself, given that it was undertaken in a context where Castile was still waging war within its own territory against the Arab world, and had no developed commercial infrastructure or even a sufficiently powerful naval fleet to carry it out. In the context of a deep economic crisis – which would end with the revolt of the Castilian Communities – it is questionable that Castile had sufficient military and, above all, nautical capacity to launch a transatlantic expedition. Significantly, the first Castilian consulate – that of Seville – was created in 1543.

But the definitive proof of the point of departure of Columbus’ expedition is provided by Antonio de Herrera on the title page of his work “Historia General de los Hechos de los Castellanos en las Islas y Tierra Firme del Mar Oceano”, where in both editions of 1601 and 1726 there is an engraving that theoretically aims to illustrate “the town of Palos” in Andalusia when in reality it is meticulously representing the silhouette of the town of Pals d’Empordà. You only have to look at the engraving to quickly recognise its characteristic bell tower. Even so, the three caravels are depicted, which curiously carry the Catalan flag, something that is repeated successively in the engravings that illustrate the interior of the work. And as if all this were not enough, the quotation that accompanies the engraving reads: “The Admiral left Palos, villa of the Count of Miranda, to discover”. For, as Spanish historiography has pointed out, the Andalusian Palos belonged to the Count of Niebla. On the other hand, the Lord of Miranda was the Count of Empúries. Let’s continue!

Palos de Moguer is undoubtedly the same case as Sant Esteve de les Roures, two places that do not exist, nor have they ever existed!

The point of return and reception of the expedition

Today we know for certain that the Catalan admiral Christopher Columbus was received with full honours by the Catholic monarchs at the Royal Palace in Barcelona on 3 April 1493, after completing the first transoceanic voyage. And this event – accepted by all historiography – was totally silenced by the official version until not so long ago.

For centuries, both Portugal and Andalusia held this narrative, until the emergence of the study by the historian Antoni Rumeu de Armas, who, in his extensive work “Colón en Barcelona” – published in the midst of Franco’s dictatorship (1944) – had the courage to document the arrival of the Discoverer of America in the Catalan capital. Rumeu de Armas’s study was a key work for the future of Columbus studies, and contributed with an innovative investigation – in terms of the detail and precision of the research – in testifying how the city of Barcelona played a fundamental role in the discovery of the “New World”. Since then, documents of all kinds have continued to appear that prove that the discoverer was received in Barcelona.

Rumeu de Armas was able to demonstrate that the official version was built on a falsehood when it spoke of Palos de Moguer as the place of departure and return of the expedition. The analysis of the documentation – especially the ship’s log – made it possible to prove that the Pals de Empordà-Barcelona pair were the expedition’s true departure, return and reception points. It is also clear from the ship’s logbook that the expedition was planned as a reconnaissance voyage. Therefore, of a short duration and with a more or less fixed return.

On this first voyage, Columbus had managed to find the lost continent spoken of in countless ancient texts: the lands on the other side of the Atlantic “which had been cut off since the sinking of Atlantis”. And as proof of this discovery, of this “New World”, he presented to the royals and high authorities of the kingdom, the natives, animals, precious metals and plants that they had brought back. Reliable proof that they had come from lands hitherto unknown.

Even so, the Catholic Monarchs – from the summer of 1492 – stayed between Barcelona, Girona and Figueres, as the Principality was involved in a territorial conflict with the French, who had invaded Cerdanya and Roussillon in order to exchange them for the kingdom of Naples. King Ferdinand the Catholic – who was looking after the interests of his states – began to organise the military defence of the territory. It was for this reason that both monarchs, being in Catalonia and knowing that the expedition was only a reconnaissance expedition and, therefore, of short duration, waited for Columbus to return to Barcelona. It was there that a Portuguese delegation arrived to negotiate the distribution of the newly discovered lands, a process that would end with the Treaty of Tordesillas. And it was also there that the papal donation documentation arrived – from Pope Borja, “il papa catalano” – which would be made public by Bishop Pedro Garcia of Barcelona. Moreover, contemporary chronicles explain that the audience in Barcelona had a great echo and that the reception was a really popular and spontaneous celebration, with all the people of Barcelona celebrating in the street, a fact that is not recorded in any of the Castilian chronicles.

As Father Casaus’ chronicle explains, the gold that arrived from Columbus’ second voyage was confiscated in its entirety by the kingdom’s officials and customs officers, which made it possible to pay for the campaign to recover the Cerdanya and Roussillon, and to finance the construction of the fortress of Salses. But the most worrying event occurred during the course of the third voyage, when Francisco de Bobadilla – with broad powers to judge the admiral – confiscated all his merchandise, arguing that not all the promised wealth had been sent to the Crown. Thus began a veritable campaign of public discredit that would end with Columbus’ arrest.

All documentation on the trial against Columbus has disappeared. From indirect sources, it is known that the Crown seized all the documentation that Columbus had to provide in his own defence. It is also known that the reports on which the accusations were based were drawn up by Pere Bertran Margarit and Bernat Boïl, representatives of the Crown. Therefore, we should not be surprised at the somewhat farcical trial – something to which the Crown of Castile has become accustomed – in which Christopher Columbus and later his family became involved. In an act of extraordinary audacity, the Crown overstepped its bounds when, by means of falsehoods, it dispossessed the most famous navigator of the time of all his deservedly acquired titles.

At this point, the history of the discovery of America is an immoral issue for the Catalans. Since the 15th century, Catalanophobia has marked relations between Castile and Catalonia. We cannot continue to accept the Genoese origin of the Discoverer, we cannot continue to believe that the configuration of the crew of the three caravels was Castilian and – above all – we cannot continue to legitimise Castile as the promoter of the transoceanic expedition that led to the discovery of the “New World”, according to the official version, with the invaluable help of Queen Isabella of Castile who – with the pawning of her personal jewels – helped to defray all the expenses of the voyage. The whole thing makes no sense at all!

BASIC BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Antonio Rumeu de Armas: En Colom a Barcelona, Editorial Llibres de l’Índex, 2012.

- Eva Sans i Narcís Subirana: El Port de Pals. ANNALS de l’Institut d’Estudis Gironins, Volum LIV, Girona, 2013.

- David Bassa i Jordi Bilbeny: Totes les preguntes sobre Cristòfor Colom. Col·lecció Descoberta, Editorial Llibres de l’Índex, 2015.

- Jordi Vila: Les Capitulacions colombines de 1492: un document català. 1r Simposi sobre la Descoberta Catalana d’Amèrica, Arenys de Munt, 2001.

- Jordi Bilbeny: Cristòfor Colom, príncep de Catalunya, Proa, Col. Perfils, Barcelona, 2006.

- Jordi Bilbeny: Inquisició i Decadència: Orígens del genocidi lingüístic i cultural a la Catalunya del segle XVI, Librooks, Barcelona, 2018.

11Onze is the community fintech of Catalonia. Open an account by downloading the super app El Canut for Android or iOS and join the revolution!

👏

Gràcies, Daniela!!!

En tot treball científic, per ser valorat seriosament, hi ha d’haver una publicació reconeguda en l’entorn profesional científic i revisada per altres investigadors. Això val tant per la històrica com per la medicina, la física, la química i d’altres disciplines científiques. Això és el que fan els milers de professionals i doctors a totes les universitats i instituts del món, encara que no en siguin professionals del tema. Si-us-plau, publiqueu les vostres conclusions en algun dels nombrosos mitjans amb alts índex de fiabilitat com per exemple els citats a https://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php?category=1202

Sinó, les vostres teories no deixaran de ser hipòtesis.

Estic completament d’acord amb tu, Narcís! El problema és quan ningú de l’Acadèmia vol iniciar un tipus de recerca diferent o, si més no, amb una mirada diferent. En aquest cas, ningú del món universitari ha volgut dirigir una tesi d’aquesta naturalesa. I, aquells que hem estat doctorats sabem que la investigació l’acaba avalant el Ministerio. Seguim a La Plaça.

Només parlaré de Palos, el famós port on va sortir Colom, el relat oficial diu, que era una vila de grans pescadors i mariners, etc. A banda d’aquest relat no hi ha un sol document que parli de Palos. No hi ha drassanes ni cartògrafs ni mariners.

Els romans ja explotaven les mines de Rio Tinto on neix el riu del mateix nom, d’aigües tranquil·les que passen per Palos, contaminats de sulfurs, on mai no hi ha hagut peixos en conseqüència no hi ha hagut pescadors ni mariners. Hi ha un parc temàtic anomenat “Muelle de las Carabelas” però quilòmetres més avall, a prop de La Rábida.

Gràcies, Leandre per la teva aportació. Seguim a La Plaça!

Oriol, si realment ets historiador, hauries d’asegurar-te de que les teves fonts no són un grup d’aficionats a la història sense cap tipus de pràctica científica. Quan Bilbeny i els seus sectaris comencen a afirmar estupideses, no utilitzaven CAP tipus de mètode científic. Quan a desde “Pseudoshistòria contra Catalunya” comencen a rebre pals a punta pala d’historiadors, és quan s’adonen de que escriure història no consisteix en volcar les seves investigacions mal documentades, i en moltes ocasions absurdes, i es comencen a prendre una mica més seriosament la investigació. Però tot i així, que existís un port documentat a Pals, no demostra res més que el fet de que hi havia un port a Pals. Res més. Cap document vincula aquest port a cap expedició a Amèrica.

Com a inversor d’Onze prego més rigurositat amb els articles que s’escriuen. I que no es dongui bombo a les fantasies de pseudohistoriadors sense formació. M’avergonyeix molt com a català que es practiqui pseudohistòria a l’estil espanyol, perquè no ens ajuda en res.

Atès que pel que sembla això va de tenir més o menys pedigrí a l’hora de poder argumentar, m’he permès el detall d’aportar-te els més destacats estudis historiogràfiques –on hi trobaràs amb les corresponents fonts documentals- de principis del segle XX d’historiadors d’indubtable reputació i sobre els quals es basen els estudis actuals. Tots aquests treballs corresponen al període anterior a l’obligada implantació “del espíritu de la raza” per la força de les armes. Si la curiositat no queda satisfeta, et puc facilitar més estudis històrics sobre la veritable identitat d’en Colom que són dels segles XIX, XVIII i XVII, però amb aquestes ja pots estar força entretingut una llarga temporada!

1. Lluís Ulloa. Cristòfor Colom fou català. Barcelona, 1927.

2. Ferran Soldevila. Revista Catalunya, número 46. Barcelona, 1928

3. Ricard Carreras i Valls. La descoberta d’Amèrica: Ferrer, Cabot i Colom. Reus, 1928

4. Antoni Rovira i Virgili. Història Nacional de Catalunya, vol. VII. Barcelona, 1934

5. Ferran Soldevila. Història de Catalunya, Vol. II Barcelona, Edició de 1935.

Estic absolutament en desacord amb les teves afirmacions!

Home, la mirada s’ennuvola quan es practica el cherry picking i s’omet documentació primària per adaptar el relat al que t’interessa, que és el que fan els de l’INH. Si ets historiador saps perfectament el que és el mètode científic, i saps que Bilbeny i cia el practiquen poc (especialment en la seva fase inicial, que era MOLT naïf). Actualment tenen algun historiador i fan les coses lleugerament millor, però el castell no té els fonaments sòlids, i ho saps.

Ai els dogmes de fe… ennuvolen la mirada!

I des-de llavors la mentida i la farsa continua. Esperem que aviat acabi!!

Certament, és una línia de treball a seguir. Seguim a La Plaça!

Excel.lent article que parla del historicidi més gran de castella. Només faltaria afegir l’afirmació d’en Jordi Bilbeny que va fer en els seus estudis sobre Cristòfor Colom, que feia que els catalans eren coneguts o confosos com genovesos pels castellans. Això no era cap elucubració de l’autor, era una afirmació feta, segons ell, per un descendent d’en Colom ja en el segle XVI.

Gràcies, Joan pel comentari. No ho podem explicar tot de cop, atès que hem de deixar arguments pel futur! Però sí, estic completament d’acord amb la teva aportació. Seguim a La Plaça!

Article molt interessant. Lentament la veritat s’imposa.

Està a les nostres mans canviar la mirada i la defensa de la nostra història. Seguim a La Plaça!

Gràcies Oriol! S’hauria de fer públic als mitjans de comunicació nacionals.

A poc a poc, Joan! Seguim a La Plaça.

Gran article, ben documentat i referenciat. Gràcies

Gràcies, Francesc per llegir-nos i seguir-nos! Ens veiem per La Plaça!

Gràcies Oriol per seguir sent, tu i 11Onze, dels que no porten cap motxilla ni econòmica ni constitucional.

La comparació de Palos de Moguer amb Sant Esteve de les Roures és genial.🤦♀️

És la llibertat del nostre temps! Quan el relat és gestionat per persones alienes a la realitat, passen aquestes coses! Gràcies pel comentari, Mercè. Seguim a La Plaça!

👍

Gràcies, Joan! Seguim a La Plaça!